Greg Kurras explores uncharted landscapes humans have never seen before. His journeys can take him to the bottom of oceans around the world. When he finds himself six days transit to the closest landmass, he knows even a minor medical problem can lead to a canceled trip, significant financial losses and even death. The stakes are high on these cruises.

When he and his team move 6,000 pound pieces of research equipment down to the ocean floor, there’s risk to Kurras and the crew he’s contracted. As a marine geologist and geophysicist, his Bellingham-based business, Seafloor Investigations, provides a breadth of international underwater data, shedding light and scientific understanding onto the least traveled terrain of our planet.

To get an idea of how living on a research vessel might feel, Kurras illustrated, “Imagine locking yourself in an average sized house for 30-45 days. You’re not allowed to leave the house. There’s 30 other people living in the house and you’re all roommates. You work every day together, eat every meal together, you see each other in your pajamas in the hall and when you’re on the back deck handling multi-million dollar equipment. You get to know people better than you want to know them. It can be fun. They become kind of like family, and then, they all disappear. You may get to the see them again or you may never see them again.”

Kurras’ career began in graduate school at the University of Hawaii. His training in Ocean Engineering and Sonar Design helped him learn how to make maps of the seafloor and find things people have lost at the bottom of the ocean. A specialized skillset he’s developed over the last 25 years; mapping has given him a variety of long and short-term assignments around the world. He’s worked with industry, commercial, academic and government groups.

Back in the early 2000s, Kurras worked for Fugro. He recalled, “I would be coming from San Diego and a friend of mine would be coming in from South Africa and we’d meet up somewhere in the world on a ship. I’d get him something he couldn’t get in South Africa in trade for African red bush or Rooibos tea.” Kurras still has community scattered all over the globe. He explained, “In our industry, the technical experts bump into each other again and again.” When he runs into old friends in remote corners of the sea on research vessels, those friendships become a welcome diversion from time away from loved ones back on land.

Kurras was once assigned to help find Air France Flight 447 that went down in the Atlantic in 2009 en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. In 2011, after only two weeks out, he and the crew found the missing box. He has also contracted with well-known companies and organizations such as British Petroleum and the Woods Hole Oceanic Institute.

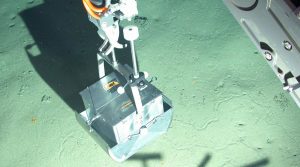

In 2011, Kurras was hired to help acquire near bottom photos to assess the damage to deep-water coral systems in the immediate area of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Recently, he helped the National Transportation and Safety Board find the block box of the El Faro- the tanker that was lost at sea with all hands in October 2015.

Since Kurras began his own independent company in 2009, his main focus has been almost exclusively deep ocean exploration at a 1,000+ meter water depth. From the North Pole, Norway, China, the Pacific and throughout the world, he’s personally seen depths of 2,500 meters (in the Alvin Submarine) and sent guided Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) down to depths of 6,000 meters. Kurras leases AUVs for his own business, describing them as “unmanned torpedo-like robotic computers (without explosives).” The AUV’s come in many shapes and sizes. Some of the devices he’s worked with on various projects have been worth millions of dollars.

In Seattle, for Fugro, Kurras remembers the first time he programmed AUVs to do his research bidding. He explained, “You program them, say here’s where you go, here’s what you do and you throw this expensive piece of equipment off the boat. It goes away and you hope it comes back in the allotted time.” Kurras knows of two AUVs that didn’t return but that wasn’t on his watch. Precise timing, unifying engineering across multiple disciplines and a year and a half of tinkering and testing in Hawaii, proved the program produced AUVs that did in fact return.

When looking to the future Kurras explained, “Now that we’re here in Bellingham, and now that I have a two and a half-year-old, I’d like to develop more coastal work.” Starting a small, cheaper, 100-meter depth coastal project and AUV programs would allow Kurras to work with organizations like the Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic Atmospheric Association and PNW tribal groups interested in salmon fisheries.

Bringing Seafloor Exploration’s deepwater knowledge to a more local level would, “Bring our skillsets from deep water exploration to help people understand the smaller bays and waterways of our area, for whatever reason, be it engineering, science or conservation,” Kurras remarked. With federal funding for scientific research in danger, private companies can provide cost effective and technologically advanced services, like AUVs, to complete research quicker and for much less. Kurras explained, “With the technology we use, I can go out in Bellingham Bay with a small AUV, sit there on the dock, launch and control it, monitor and map within a day or two.” He added, “We have a lot of experience mapping, photographically imaging and sampling the ocean floor and water column.”