At the turn of the century, Bellingham’s schools faced a crisis as enrollment skyrocketed. Even as he struggled with a limited budget, Elmer Cave, superintendent of Bellingham Public Schools from 1909 to 1920, helped make the city’s schools the envy of the state.

California’s Son Elmer Cave

Elmer Lafayette Cave was born March 5, 1870, to Marcus Lafayette (1828-1906) and Frances Haun Cave (1844-1928) in the San Ramon Valley. He graduated from San Jose’s California State Normal School in 1890 and attended the University of California for two years. Cave taught in (and served as vice principal) at San Ramon, Berkeley, Antioch, St. Helena and Alameda.

Cave married Stella T. Austin (1875-1945) in 1895. The couple had two children, Hobart (1896-1964) and Donald (1908-1973).

In 1909, Cave heard of a new opportunity: the Bellingham School District was looking for a new superintendent of public schools.

Bellingham Superintendent of Schools

Cave applied and was hired, beginning work July 1. “I trust that my term in office,” the Bellingham Herald quoted his report to the school board, “may be characterized by hard, intelligent work, which will result in progress of a constructive nature in the school department of this city.”

Among his first acts, he reorganized the school system, shifting grades between schools in hopes of easing the district’s most pressing problem: overcrowding.

Elmer Cave Expands the District

The district desperately needed new and bigger schools, as hundreds of new students enrolled every year. Cave dedicated much of his tenure in Bellingham to making this possible. In 1915, he campaigned across the city for a school bond election, talking to community groups. The bond passed, and work began immediately. A new Lowell School was built that summer, but it did little to ease overcrowding. That fall, students were sitting two to a seat in several schools.

Whatcom High School was built in 1916. Overcrowding remained a continuing issue.

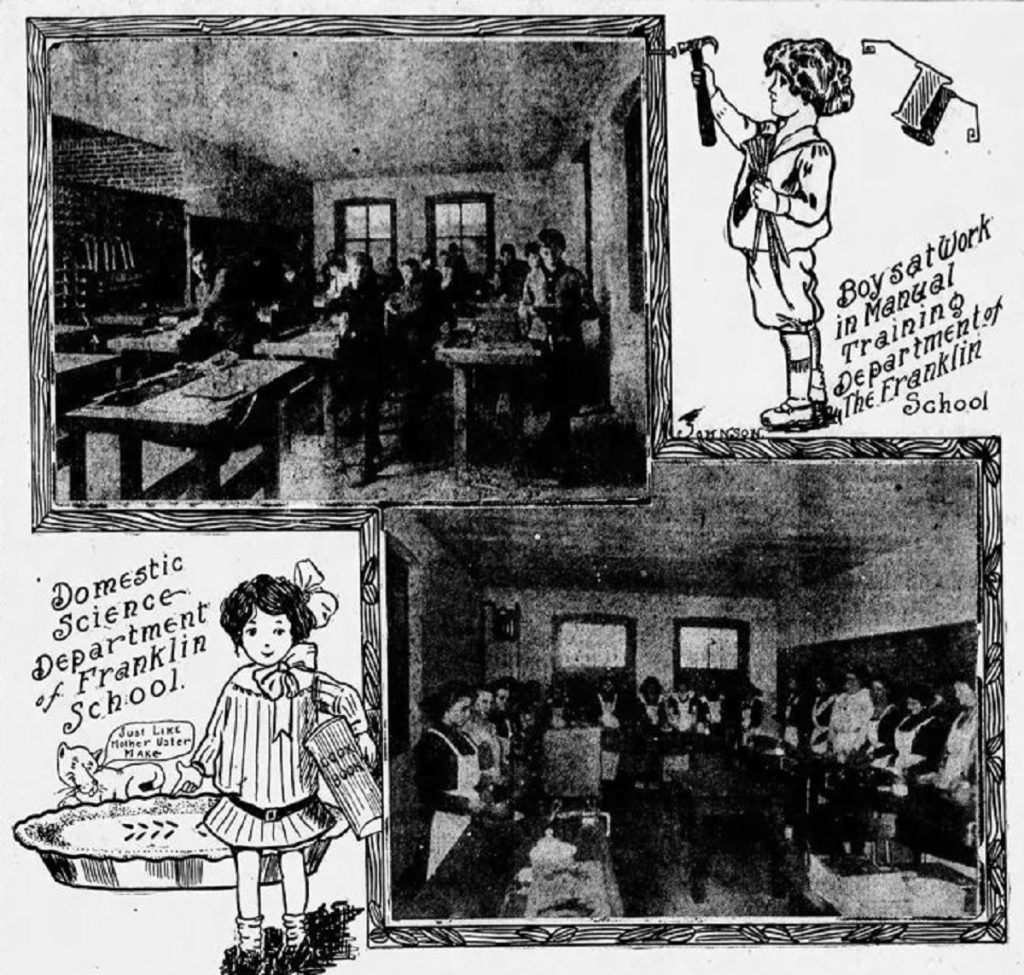

At the same time as Cave promoted the district’s physical expansion, he also championed expanding its educational offerings. He promoted increased vocational training for students and started night schools for adults.

Cave did all this with an eye to the budget. He bragged in 1914-1915 that the city’s $52.65 per capita cost for schools was the second lowest among the state’s largest cities.

Elmer Cave as an Educational Leader

The educator spent much of his time inspecting schools across Bellingham and talking to community and parent groups. Cave also spoke at Teachers’ Institutes graduations and lectured at Bellingham Normal School (now Western Washington University) about school administration.

Cave was recognized as one of the state’s top educational leaders. Active with the Washington Education Association (WEA), he served on legislative committees drafting and promoting school-related bills. He was the president of WEA for four terms. He also served on National Education Association (NEA) committees and regularly attended their annual meetings.

As superintendent of education, Cave was active in Bellingham’s civic and reform clubs. He served as the Twentieth Century Club president in 1910 and was selected for the County Welfare Board in 1919. He was also active with the Chamber of Commerce.

Stella Cave was also active in the community. A singer and piano player, she regularly performed at club gatherings. She belonged to P.L.F. and the Bellingham’s Woman’s Music Club and served as choir director at First Presbyterian Church. During World War I, she organized the making of “comfort kits” for submarine sailors through the National League for Women’s Service.

World War I

Elmer Cave dedicated much of his time to the war effort. The educator promoted a new curriculum, “Our Country.” to teach the children about the war and their duty to support it. He also chaired the Chamber of Commerce’s War Garden committee to help conserve food and the Red Cross’ Civilian Relief committee. In August 1918, he auctioned off two goats “belonging” to the Kaiser and crown prince at a Red Cross dance.

Cave served on WEA and NEA committees to study the current educational emergency. In February 1919, he took a leave of absence to help with the YMCA-financed educational program in the Paris-Versailles area. Headquartered in Paris, he oversaw literacy and extension programs for soldiers waiting to return to America. Cave returned to Bellingham in July.

Elmer Cave Leaves Bellingham

In 1920, three school board members were threatened with recall. But Cave was the real target of the attack, the papers said. This should not have been a surprise, as Cave’s prominence brought both support and opposition. In 1911, someone unsuccessfully petitioned the county superintendent to revoke Cave’s teaching license on the grounds of having teachers pad attendance rolls.

Cave was reappointed superintendent in 1913 for a three-year term, but the renewal of his contract in 1916 was met with some opposition from the school board. In 1920, a group petitioned for a recall election against him and two school board members for mismanagement and poor hiring decisions. The case went up to the state supreme court, which ruled against the recall on technical grounds and labeled it a clash of personalities.

By then, Cave had resigned and moved to California to direct Vallejo’s schools, a job he held until his 1941 retirement. He visited Bellingham several times while traveling to Seattle to see his son Hobart, a dentist. Stella passed away in 1945. Cave moved to Seattle, where he died on November 3, 1946.

The Vallejo School District built Elmer L. Cave Elementary School in 1953 to honor their longtime leader. Now a TK-8th grade Spanish-English dual-immersion school, Elmer Cave Language Academy continues his legacy of education. Bellingham could say the same, as the schools Elmer Cave did so much for to continue to thrive.