Like all of Washington and the United States, Bellingham has its distinct milestones in the history of women’s suffrage and fight for social equality. Frances Axtell, remembered locally by her historic home and activity in social clubs, was one such pioneer whose advocacy for suffrage influenced her own path to passing reforms in elected office.

Born Frances Sevilla Cleveland in 1866 in Sterling, Illinois, Axtell earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at DePauw University in Indiana. She married William Axtell, had two daughters, and soon taught mathematics and Latin at Northwest Normal School: the teachers’ school that would become Western Washington University.

Axtell was a founding member of the Whatcom Ladies Cooperative Society and Aftermath Club, literary and social organizations that promoted women’s education and influence in public life. These organizations supported others such as the YMCA and YWCA and implemented the era’s movements for social reform at a local level.

Axtell’s grandson William Hussey stated she was of “strong character — totally honest — fearless.” These qualities drove her to succeed and set other precedents for women’s success in public office.

Strides in Reform

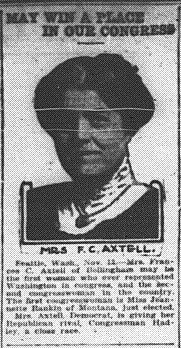

Frances Axtell gained her nickname in the press, “the lady from Whatcom who votes as she pleases,” for her advocacy work before and after becoming one of the first two women elected to Washington’s State Legislature. Axtell worked with Emma Smith DeVoe of Tacoma, Washington’s “Mother of Women’s Suffrage,” to restore women’s right to vote (once available in Washington Territory) by 1910. These very actions made her 1912 run and 1914 reelection possible.

In office, Axtell supported contemporary causes such as banning child labor, promoting reforestation, and establishing a minimum wage, workers’ compensation, and pensions. She ran on the Republican ticket but advocated reform across party lines, hence “voting as she pleases.” Perhaps Axtell’s biggest influence was public safety legislation on handling evidence in cases of violent assault.

Ella Rhoads Higginson, Washington’s first poet laureate by 1931, became Axtell’s campaign manager. In 1914, Higginson wrote a screenplay called Just Like the Men for a shelved silent film planned to star Mary Pickford and fictionalize the story of women running for office against men in Washington. Laura Laffrado rediscovered it at Western in 2012, and Talking to Crows modernly adapted it as a streaming film in 2020.

Axtell wrote on her motivation to enter politics: “Women look at life from a different angle than men, and both viewpoints should be represented. Most men are in politics because they want to do something or somebody, whereas women are in it because they want to get something done. Then, too, women are not bound by party fealty; they vote for what they think is right and for the people they think will do what is right regardless of party.”

Onward and Upward

Axtell unsuccessfully ran to become a United States senator as a Democrat in 1916 and as a Republican in 1922. However, President Woodrow Wilson took an interest in her labor advocacy and appointed her to the Federal Employees’ Compensation Commission in 1917. Axtell was the first woman with such a federal commission appointment, which she learned by surprise over telegram.

That same year, Axtell spoke at the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention. Her federal role involved surveying the U.S. navy yards during World War I, ensuring compliance with the safety measures and workers’ compensation she had advocated before. Axtell served as the commission’s chair from 1918 to 1921. The New York Times stated this appointment in the commission was “in recognition of her services as one of its members.” She moved back to Bellingham after this term ended.

Press would call Axtell the “mother” of 500,000 federal government workers for her dedication. She became a supervisor of mothers’ pensions in 1929 after a decade working toward the goal. Axtell spent the remainder of her life after 1944 living in Seattle, where she supported the Woman’s Century Club and University Presbyterian Church and died at the age of 86 in 1953.

Local Legacy

The Axtell House and Aftermath Club buildings still stand in Bellingham, both on the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1902, Axtell House (413 E. Maple St.) exemplifies the Classical Revival architectural style and served as a gathering place for organizers until Frances Axtell moved out in 1942. She helped convert the house into apartments in 1926, creating the purpose it still serves today.

Aftermath Club sold their building in 1977 and continued to operate until 2003, at which point the senior members supported Western scholarships as a final philanthropic venture. Built in 1904, Aftermath Clubhouse (now Broadway Hall) has Mission Revival architecture influenced by Italian villas in California. Westford Funeral Home now operates the building as a venue for weddings, funerals, parties, and other community events.

The City of Bellingham has called these buildings “the only direct connection to the amazing life and work of Frances Axtell.” However, her influence is also felt as one of the many in understated public roles who blazed a trail for a more equitable and free society.