On Bellingham’s Telegraph Road, just east of Bellis Fair Mall, a weathered wooden signpost clashes with the urban sprawl. Titled “Old Telegraph Road,” the sign describes how a telegraph line ran along the modern road’s route from 1865 to its abrupt discontinuation in 1867. This was Bellingham’s link to the story of the Collins Overland Telegraph, both an economic failure and far-reaching inspiration.

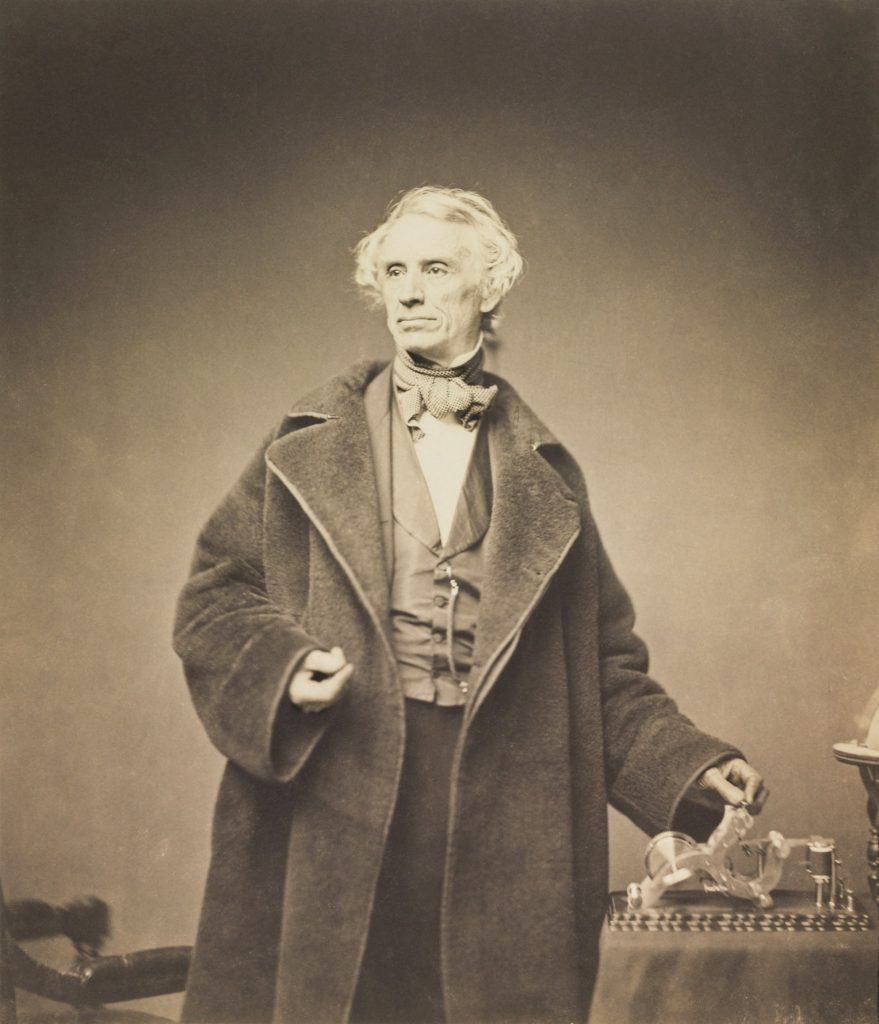

The invention of the telegraph entranced the nation with the prospect of sending long-distance messages within minutes. Samuel Morse presented the wired electrical device in 1835 and patented Morse Code, a system of communication using dots and dashes, in 1840. After the first telegraph line spanned from Washington, DC to Baltimore in 1844, demand for a transcontinental line emerged. Western Union Telegraph Company completed the first in 1861 and started the Russian-American Telegraph Company to go international.

As Bellingham’s lonely sign shows, the prospective line would have linked New York and London via the Bering Sea through Alaska and Russia. The project cost $3 million, only to shutter when the undersea transatlantic cable first succeeded. But beyond spiriting modern visitors to Bellingham’s thoroughfare away to another time, this venture would influence local communications and the 1867 Alaska Purchase.

Bellingham in Telegraphy History

The Collins Overland Telegraph, passing through Bellingham on the way to Alaska, ignited at the spark of undersea telegraphs failing since 1858. Perry Collins envisioned an overland line with only 40 miles of undersea cable between Russia and Alaska. Western Union’s first triumph had made the Pony Express of 1860-1861 synonymous with innovations that quickly became obsolete. They projected the American-Russian line’s profits as $9 million per year.

In Bellingham — then four towns in Washington Territory — John Fravel oversaw construction of Western Union’s line. He originally helped build an interstate line through the California State Telegraph Company. It terminated at New Westminster, B.C., which would become the intercontinental line’s starting point via Bellingham.

While Western Union’s first transcontinental telegraph followed the path of the California Gold Rush, its American-Russian line followed Whatcom Trail of Fraser River Gold Rush fame. A traditional Lummi and Nooksack travel route, this trail became a gilded hotspot for prospectors in 1858. The trail and telegraph ran northeast through present-day Cornwall Park and Hannegan Road to Everson and Sumas.

Bellingham’s modern-day sign recounts: “A single-wire pole line followed a fifty-foot clearing through heavy forests and across frozen tundra.” Ultimately, the constructed line spanned 800 miles into British Columbia, with Russian portions underway before Western Union just as quickly cut the cord.

North to the Future

In 1866, entrepreneur Cyrus Field built the undersea transatlantic cable that spelled the end of Western Union’s overland project. When it survived the winter, Western Union officially shut down the American-Russian project in July 1867.

Under Western Union, John Fravel continued to maintain Bellingham communications with British Columbia through the existing line. He led the restoration of its line to Hope and continuation to Kamloops starting in 1870. Victor Roeder paid him $39 to dismantle old lines in 1881. By 1885, the official Telegraph Road started at Roeder Home onto the telegraph’s northeast route through Meridian Street and Squalicum Creek toward Everson and Sumas.

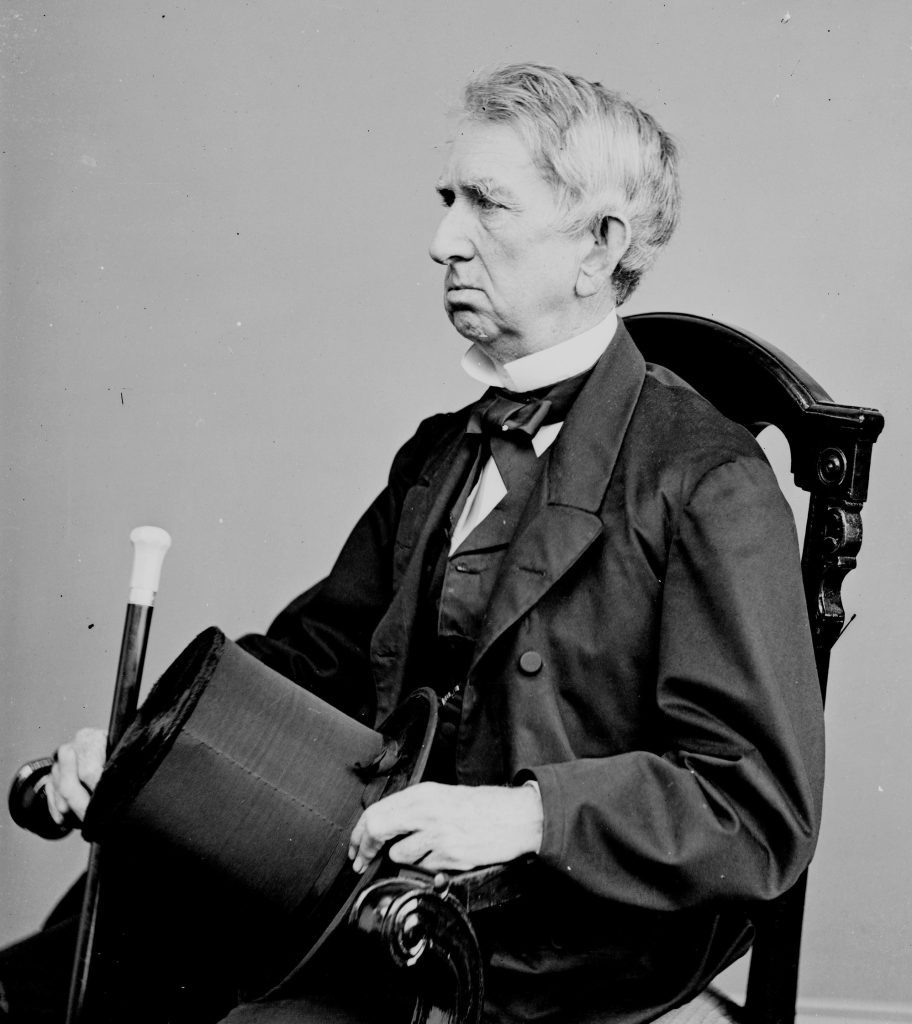

Per the modern road’s sign: “Russian-American cooperation in building this line facilitated our purchase of Alaska in 1867.” In fact, Secretary of State William Seward learned of the telegraph project as Collins lobbied Congress for support. Smithsonian scientists reported Alaska’s mineral wealth in gold on expeditions to building sites, likely influencing Seward’s negotiation with Russian minister Eduard de Stoeckl. (The rush for Alaska’s gold and oil also eventually shifted public opinion in favor of “Seward’s icebox.”)

New Telegraph Road Meets Old

Today, Bellingham’s Telegraph Road spans just over one mile. Since the start of Bellis Fair Mall in 1988, the area bears no trace of its pioneering past but the sign by the State Parks Commission. At Cornwall Park, a 1941 plaque by the Chief Whatcom Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution states, “Here passed the old Telegraph Road.”

Other “Telegraph Roads” along the same line tell its history throughout British Columbia. At the end of the line, the unincorporated community Telegraph Creek takes its name from the historic venture. One of Bellingham’s best-known attractions, SPARK Museum of Electrical Invention, today showcases ephemera from the age of telegraphy.

Bellingham’s economic ties to Alaska would continue with the heyday of Pacific American Fisheries, which operated canneries there and in Fairhaven from 1899 to 1965. Since 1989, Bellingham Cruise Terminal has operated the southernmost ferries in the Alaska Marine Highway System. But only historic markers that have become artifacts unto themselves convey the curiosity of these regions’ earliest telecommunications. When the dream of instant communication was born, a new world of innovation opened locally and worldwide.