Before becoming part of Bellingham, Fairhaven grew up along railway lines. The town boomed with the region’s industries — fishing, lumber, and mining — into the 1870s, seeking the Northern Pacific Railway terminus. After the railway instead went to Tacoma, in 1873, multiple economic panics drove Fairhaven into a depression by the 1890s. However, Fairhaven soon found economic revitalization in what would become the largest salmon cannery in the world: Pacific American Fisheries.

Whatcom County’s early settlers viewed the salmon crowding every stream as an almost inexhaustible resource. Fisheries would prepare salmon fresh, dried, salted, or smoked, but turned most into hog feed and fertilizer. Whatcom County had 11 large canneries by 1899, but many shuttered within years due to mismanagement.

Financed by C.X. Larrabee, Roland Onffroy started North Pacific Packing Company on a similar path in 1898. When this first venture went bankrupt, Onffroy sought investment from Chicago brokerage firm Deming & Gould. Everett B. Deming would direct Pacific American Fisheries from its 1899 incorporation until his death in 1942.

By its peak, in the 1940s, Pacific American Fisheries had become Whatcom County’s biggest employer. Its influence flowed overseas to and from Alaska and China — the sources of its fish traps and migrant labor, respectively. While the cannery closed in 1966, it spawned regional connections that thrive to this day.

North to Alaska

In 1906 and 1907, Pacific American Fisheries bought Alaskan canneries in Haines and Excursion Inlet. These acquisitions proved essential to the fishing operations’ survival when Washington banned fish traps in 1935. Even earlier, heightened demand for canned salmon in World War I led to overfishing in the Puget Sound.

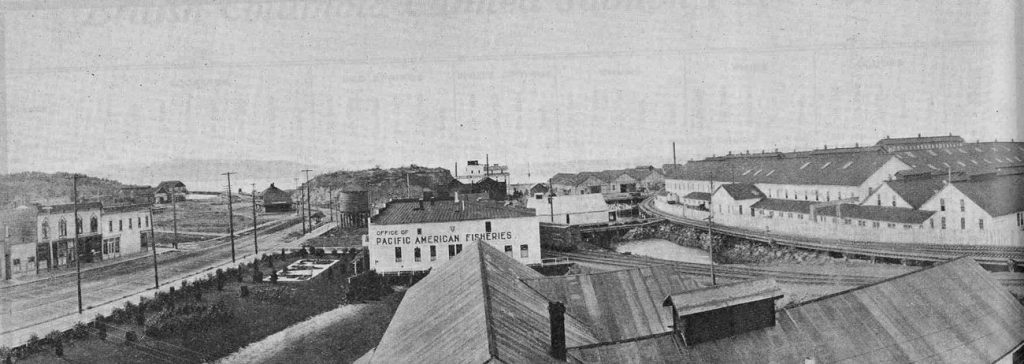

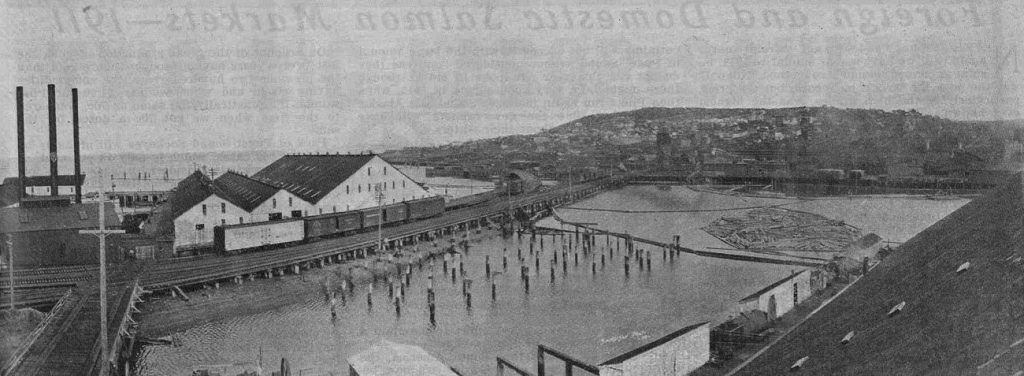

Pacific American Fisheries’ Fairhaven compound incorporated the Ocean Dock: Whatcom County’s first ocean shipping facility, built 1889. It shipped cans to ports across the coast, supplying markets in Europe and the South Pacific. The warehouse compound included a cannery, shipyard, can and box factory, and bunkhouse for Chinese workers.

Pacific American Fisheries also incorporated the 1896 Fairhaven Canning Company facility, whose waste became the notorious “tin rock” in present-day Boulevard Park.

By its peak, Pacific American Fisheries provided jobs to over 4,500 Bellingham locals and over 1,000 Chinese laborers. The facility could pack anywhere from 42,000 to 756,000 cans daily, and mechanization gradually reduced its workforce. Between 1942 and 1944, the cannery leased its shipyard to Northwest Shipbuilding Company to meet World War II demands for military vessels. Northwest Shipbuilding Company became another of Bellingham’s largest employers, with over 1,000 employees building over 25 ships.

Pacific American Fisheries closed within years of Alaska becoming a state and banning fish traps in 1959. Other factors precipitated its closure: refrigeration largely replaced canning as a food preservation method, and cannery workers unionized.

Chinese Labor

Chinese entrepreneur and diplomat Goon Dip became Pacific American Fisheries’ labor contractor in 1909. After becoming Chinese Consul of Seattle earlier that year, he arrived in Fairhaven with San Francisco Consul General Hsin Ping. They had boarded the Great Northern train during the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition at Seattle’s World Fair.

E.B. Deming and Goon Dip had associated professionally since 1900 and became personal friends. In 1909, Goon Dip presented an empress tree as a gift outside the Pacific American Fisheries facility. Deming would act as pallbearer at Goon Dip’s 1933 Seattle funeral.

Chinese laborers occupied the “China House” at the cannery complex. Contemporary writings describe a first-floor noodle house that Fairhaven locals would visit, paying 10 to 15 cents for each bowl of noodles. Many transient workers arrived seasonally from Portland and San Francisco.

Historic markers in Fairhaven today note the racist discrimination that Chinese laborers faced. The “Chinese Deadline” prohibited them from entering town beyond 8th Street and Padden Creek. Decades before, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had precedented the expulsion of Chinese immigrants from communities across the Puget Sound, including Bellingham. Many publications used hostile rhetoric, infamously nicknaming the salmon processing machines with a racial slur.

In 2011, Bellingham’s mayor apologized to the Chinese community. The updated “Chinese Deadline” marker commemorates this apology alongside a quote from Confucius written in Chinese: “Study the past if you would divine the future.”

Pacific American Fisheries’ Legacy

Since 1989, the Bellingham Cruise Terminal has maintained Fairhaven’s highway to Alaska through its ferry system. The Port of Bellingham continued labeling cans at the facility from its closure to the new terminal’s construction.

Interpretive signs outside Bellingham Cruise Terminal recount Pacific American Fisheries, its shipyard, and the Lummi people’s continued stewardship of the region’s aquaculture. Salmon runs are still gradually recovering from overfishing.

The 1909 empress tree that Goon Dip gifted to E.B. Deming still stands outside the Amtrak station. One of the oldest specimens in the country, the tree still flowers past its typical 70-year lifespan. Local garden clubs have organized to preserve the tree, which bears its own plaque.

Anacortes Museum preserves memorabilia from an additional cannery there. But perhaps the greatest remnants of Pacific American Fisheries can be seen in the port city it helped build. Like the salmon, Fairhaven’s industry travelled through Pacific channels and always returned home.