When most Americans hear “the Gold Rush,” a few chapters of history come to mind: California in 1848, Colorado in 1858, and Klondike in 1897. These events cemented themselves in our cultural consciousness with stories of prospectors from all walks uprooting their lives in search of riches that few found. But smaller gold rushes nationwide also caused economic booms that went bust within months or years. Two such prospects guided Whatcom County’s early development: the Fraser River and Mount Baker Gold Rushes.

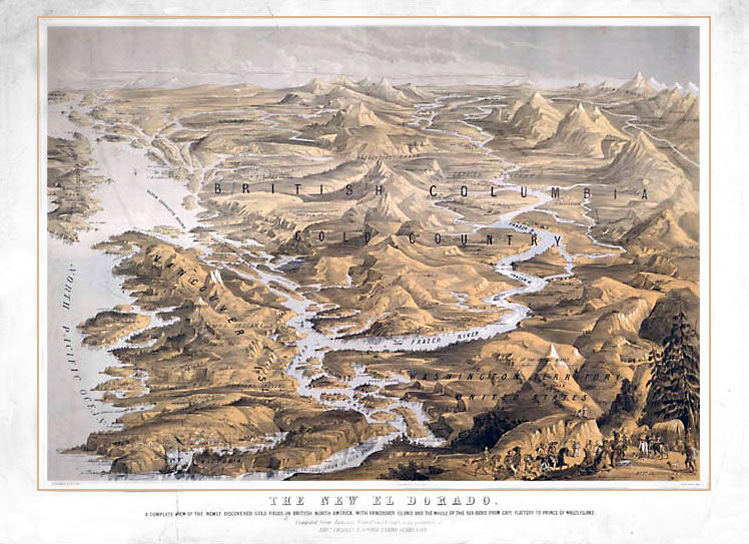

Whatcom County’s gold rushes came on the heels of the national gold fever. While smaller than the California Gold Rush, the Fraser Gold Rush saw thousands of California miners arrive in the country’s largest movement of mining populations.

Digging into these events reveals not only Whatcom County’s place in the national story of gold rushes, but the formation of its local identity. Whatcom — one of four towns that ultimately became Bellingham — and settlements in the Mount Baker Foothills grew around the national pursuit to brave the wilderness and strike it rich.

Fraser River Gold Rush (1858–1927)

The Fraser River Gold Rush started in 1858 after the publicized discovery of gold on British Columbia’s Thompson River. First Nations people, such as the Shushwap, had traded gold with the Hudson’s Bay Company years before. Starting at roughly 500 people, Victoria saw an influx of over 30,000 men. They were European and African American, English, and French Canadian, Chinese, British, French, Italian, German, Mexican, and Hawaiian, among other nationalities.

Whatcom’s population similarly boomed from a few hundred to over 10,000 as it became miners’ overland portal to the goldfields. The Whatcom Trail spanned eastward from Bellingham Bay against Victoria governor James Douglas’ edict. The population would decline back into the low hundreds that same year after Douglas required miners to get licenses there.

The Fraser Gold Rush heralded Whatcom’s earliest developments. Houses, encampments, and merchants sprang up everywhere, meeting demands for supplies and luxuries such as champagne, glasses, and silverware. Industry boomed as Henry Roeder built a sawmill on Whatcom Creek and the T.G. Richards and Company Store supplied prospectors.

Although some miners found success, thousands denounced the Fraser as “humbug.” Used to sifting through California’s shallow streams, they struggled with the Fraser’s high waters and their prospects never panned out. But wealthy prospectors such as Marietta founder Solomon Allen went on to drive the region’s gradual post-boom growth into a modern seaport.

Mount Baker Gold Rush (1897–1924)

The Mount Baker Mining District started when Jack Post, Russ Lambert, and Luman Van Valkenburg staked a claim for the Lone Jack Mine in 1897. That August, Post discovered ore bearing gold flecks in a quartz vein on Bear Mountain. As Michael G. Impero describes in The Lone Jack: King of the Mount Baker Mining District, this discovery sparked a gold mining boom throughout the North Cascades. Boundary Red Mountain, Gargett, and Excelsior were among the producing mines to join the Lone Jack.

The Mount Baker Gold Rush caused Glacier to boom as Whatcom had decades before. Thousands of men left Whatcom on a wagon road through Kendall and Maple Falls — then named Keese and Hardan, respectively. Tent camps such as Gold Hill, Gold City, and Trail City accommodated miners who had to travel by foot or pack animals through mountain wilderness. Gold Hill became a boomtown called Shuksan, which had 1,500 residents at its peak but lasted only a few years. In 1904, the Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railroad came to Glacier.

After buying the Lone Jack claim for $40,000 in 1897, the Mount Baker Mining Company struggled with the harsh mountain environment. They built structures such as a stamp mill, bunkhouse, tramway, and offices, some of which succumbed to fires and avalanches. After 1907, the Lone Jack changed hands through multiple companies that produced gold into 1924. Later private owners would only mine the remaining ore in 1995.

Keeping Whatcom Searching (For a Heart of Gold)

“Nothing gold can stay,” as the poet Robert Frost tells us — but Whatcom County’s memories of gold remain.

Thousands stayed in Victoria after prospectors’ mass exodus from the goldfields, eventually leading to British Columbia’s 1871 foundation. This era’s articulation of territorial boundaries would also influence British relations with the U.S. and First Nations, imperial policy, and the notorious Pig War of 1859. (Lyman Cutlar, who shot the pig, arrived as a prospector.)

The consolidated Bellingham still remembers Whatcom’s golden age. Henry Roeder’s mill is no more, but the foundations lie on Whatcom Creek and T.G. Richards Store still stands as Washington’s oldest brick building. A portion of Whatcom Trail became Telegraph Road, named for the line running through it from 1865 to 1867.

Glacier, Maple Falls, and Kendall have maintained populations of just a few hundred since the Mount Baker Gold Rush days. The original wagon road to Glacier corresponds with the Mount Baker Highway’s modern route. The Lone Jack and other mines remain under private ownership — although some, such as Shuksan and Excelsior, linger as ghost towns.

Even if Whatcom County’s prospectors never found their El Dorado, they did help build cities and towns with brilliant histories still waiting to be discovered.