Accomplished international artist Jyoti Duwadi was born in Nepal and moved to the United States in 1971 to attend school in Missoula, Montana, on a scholarship. But he didn’t come here to study art. He had an undergraduate degree from Kathmandu in political science and public administration and planned to pursue an advanced degree in political science.

He then moved to California to seek his Ph.D., also in political science. In fact, his route to art – and, eventually, Bellingham – is peppered with fortuitous circumstances.

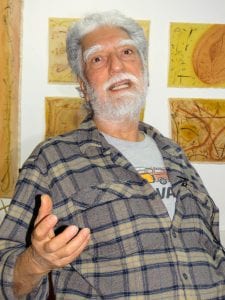

Sitting with him in his Bellingham studio, politician is the last thing you’d imagine. Duwadi is casual, comfortable, humble, and kind. The studio is warm and filled with earthy colors from the surrounding artwork in which he primarily uses ground terrestrial pigments from a variety of sources. But art and politics aren’t unrelated. “Art is politics, politics is art,” he says.

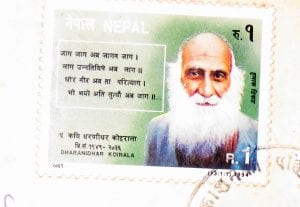

“I grew up in the middle of a revolution, things were happening. Politics, art, literature, poetry. Art and literature wasn’t new to me,” he says. Duwadi was always involved in art, coming from a literary and artistic family. His grandfather was the well-known social reformer and Nepalese poet, Dharani Dhar Koirala, who is featured on a Nepalese stamp.

Duwadi didn’t see himself as a poet, though. He fantasized that he might one day work for the U.N.

He carried this legacy of art and politics in his bones as he traveled to Montana, and then California, furthering his education in the ’70s. But like many Ph.D. students, he began to suffer from burnout. He’d finished his classes for the Ph.D., but not yet his dissertation, when fate or just pure chance seemed to intervene.

Duwadi had rented a carriage house in which to live while he studied, and beneath the home was a long garage-type space, made of stone. Duwadi felt restless and needed something to get his mind off of school. He used the space to start making art, because he knew art made him feel good.

One of his professors, Carl Hertel, asked to see Duwadi’s studio. He loved what he saw and encouraged Duwadi to keep making art. He also told him he must have a show. “I had my first show at Pitzer College Salathe Gallery in 1978,” Duwaldi says. People liked what they saw and asked for more. Duwadi moved forward, making more art and hanging it in galleries.

When Duwadi’s grandfather – who had really wanted him to finish his Ph.D. – died, Duwadi took a year off of art in his honor, completing his dissertation. He then immediately went back to art.

“It was kind of hard at the beginning, but luckily I got a job at the graduate school running their audio visual department,” Duwadi says. He negotiated a reduced two-day schedule, leaving plenty of time to work on art for the rest of the week.

Duwadi became involved with the California Fringe Festival, and was one of the founding members of the Pomona dA Center for the Arts, running collaborations with artists from Berlin after the fall of the wall, and more.

Duwadi has completed eight major installations, 22 solo-exhibitions, and 40 group exhibitions. He’s shown work all over the world, including at the Smithsonian, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Pacific Asia Museum, the Sudaram Tagore Gallery in both Hong Kong and New York, and, among many others, our own Whatcom Museum and Big Rock Garden.

Remember when he said that art is politics? It shows in his work through projects that are meant to educate, spark change, and illuminate our shortfalls – so we can heal and do better. For example, Peace Park is an installation completed in 2003 that remains standing in Kathmandu. He collaborated with women who are lower caste, “untouchables” he explains, to create a park that would grow herbs, fruit trees, and flower gardens to feed the women, revitalize the environment, and provide them an income.

After a massacre in the royal family in Nepal, Duwadi was moved to create his installation, Value, which compared the cost of weapons to the cost of rice.

Almost all of his work draws from the landscape, the soil, and the cultures that inhabit the soil he uses for paint. Duwadi draws up the Earth, washes it in the human condition, and lays it out like a beautiful Nepalese rug saying, “Look, do you see what we’ve done there?”

As in his visit to Nepal wherein he was drawn to the way that rug dying was damaging and polluting the river as, depending on the time of day, it flowed red, green, and blue from chemical dyes. “And I’d just come out of that fragile ecologies class, and I thought, I have to do something.” He and his wife, Barbara Matilsky, wrote a 20-page manifesto explaining how the dyes degraded the environment, which they took to the United Nations.

The couple put together an installation, The Myth of the Naga, using the mythological framework from Buddhist and other ideologies showing the need for caretaking of the watershed. It was a success. They garnered enough attention to help clean up the watershed and Duwaldi was convinced, under much pressure, to take a position at the United Nations.

He soon began to chafe at the increasing demands and political nature of the work. No matter how prestigious or how important, if his work couldn’t include art, it couldn’t include him. He left after ten months.

“Most of what I do has to do with chance,” he says. “Where you are, what you do, what is available. I’ve always worked like that. Pure chance.” He goes on, “Just think, it’s pure chance that I was able to find the space for art when I was procrastinating – and pure chance that I met Carl Hertel.”

In illustration of that chance, he talks about his latest series, Earth Colors, wherein he was visiting a friend at Smith and Vallee in Bow who had some large industrial sanding belts they were meaning to dispose of. But to Duwadi the huge belts were beautiful. They held the raw colorful resins from the woods the belts had polished. Mahogany, oak, pine, all have saps and resins that leave behind colorful marks when they are sanded, impregnating the belts with color and even scent. Duwadi was inspired to make them into something, to showcase the friction, and the result of friction. So it was by chance that he found them or they found him.

“The creative process has to be looked at as a whole,” he says. “When people ask me what I do, sculpture or what, I say art. It’s a creative process, a state of mind – no matter what you do. For me, cooking is the same thing.”

And that state of mind – that artful state of existing – brings things to him. From earthen samples for pigment paints given by friends, or fallen limbs just right for something interesting.

He does still have a house in Kathmandu, as well as family there, and Duwadi and his wife frequently visit Nepal. But, he says, he feels fortunate to live in Bellingham. And I can’t help but think there’s a wellspring of chance, right here in the Pacific Northwest, that he’s somehow tapped into.