Barbara Matilsky retired from the Whatcom Museum where she was a curator for nine and a half years. Her work may sound familiar; she curated the “Vanishing Ice” exhibit which went on to tour internationally. She also recently completed the “Endangered Species” exhibit. Her work, spanning decades, includes catalogues on “The Spirit of Place,” “Fragile Ecologies,” “The Expressionist Surface,” “A Show of Hands: Northwest Women Artists 1880-2010,” and more. There is just no way to list her curatorial accomplishments in one article. Maybe you saw the work of Lesley Dill a few years back? We have Matilsky to thank for that, too.

But like all the best people, Matilsky’s contributions have more to do with her way of thinking than with her job. And that, along with her passions for art, artists, the environment and our region, is more available to the community than ever. Bellingham is lucky to have her.

Matilsky was born in Brooklyn, New York, and received her PhD in art history at New York University at their Institute of Fine Arts. A recipient of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Theodore Rousseau Fellowship and another from the National Endowment for the Arts, she has worked at the Queens Museum of Art, followed by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hills Ackland Art Museum where she stayed for 13 years.

But climate change began to elevate local temperatures, driving Matilsky and her husband to seek other options. They’re outdoors people and wanted a place that offered a variety of hiking and other opportunities for recreation. Google Earth searches led them to consider Bellingham, but there were no jobs at the time.

Just two months later, however, a job opened up at the Whatcom Museum. “It was fortuitous,” says Matilsky.

Now, here they are, more than 10 years later – and loving every moment. “This is our home,” she says. “We’re not going anywhere.”

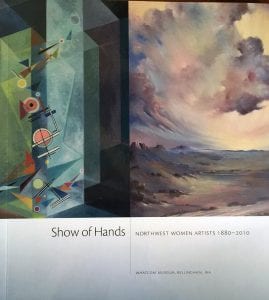

As a Ph.D., you’d expect her to be academic and scholarly, aloof and distant, but Matilsky is warm with a ready laugh, friendly and generous with her time and ideas. “We’re on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the women’s right to vote, nationwide. So this,” she says, handing me a catalogue, “documents an exhibition that I curated at the Whatcom Museum called ‘Show of Hands: Northwest Women Artists 1880-2010’ which was put together on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the women’s right to vote in Washington State, which was ahead of the times.”

With a little local pride and an easy smile, she lifts us all higher. She makes me proud to live here. And it strikes me all at once: that’s what she does. That’s just her way. She lifts the artists, women, her husband – all of the people around her. She lifts them up and shows them how great they are. Like a curator does with art.

This makes sense as her curatorial standard sounds like a life motto, “My technique in terms of curating is [to include] as much variety as possible,” Matilsky explains. “Variety of mediums, of types of people who are crafting the work.”

And her interest in inclusivity and diversity shines through.

“Oh, I’d better add to my meter,” she says, because we’re still talking. So I mention the news that Bellingham will be moving toward smartphone apps for meter payment, and she pulls up short. “What about the elderly?” she asks, immediately concerned about how we might be inadvertently excluding others in our hasty quest for advancement.

More life advice comes later when she says, “[Art] has to have a social significance, it has to have meaning and resonate beyond the art. Though I do enjoy looking at totally abstract art, there’s always something behind it, whether it’s something going on inside the artists’ head or related to the natural world. It’s filtered through the artist, so it’s not like it comes from the ether.”

Is she talking about art or life? Both, I think.

One of her greatest joys during her 30-year career as a curator came from “open hanging” shows, of which she curated just two. In these, anyone who’s a member of the museum can submit work and the curators hang the art next to accomplished professional work. This elevates the community’s body of work and humanizes the professional in a way that, again, is about inclusivity; inviting people to hang art in a museum who might otherwise never have the opportunity, while also exposing professionals to alternative or less often seen works. “That was my favorite thing,” she says. “I had so much joy in putting those together.”

Matilsky stands before the Vanishing Ice exhibit. Photo credit: Jyoti Duwadi.

Looking through a list of her catalogs, it’s obvious that Matilsky’s artistic taste has a predilection for environmentalism and social activism, things which she says have been a part of her life for as long as she can remember, and which she intends to continue to pursue.

Matilsky’s future might embrace teaching at the intersection of art and ecology, writing, working to bring environmental art to Bellingham, and/or volunteering on the Bellingham Arts Commission. For now, she’s on sabbatical, she says, though she hasn’t ruled out working with the Whatcom Land Trust or other groups that bridge her love of art, nature and words. “I want to be active in art and the environment, it’s just a matter of where,” she assures me.

The community of artists and art lovers, those who have experienced the special lift that this unique and talented woman brings to Bellingham, have expressed their sorrow at her retirement. But she assures them, too, “I’m going to be here. Let me know if you need anything.”