Visitors to Bellingham today can choose between chain hotels, Airbnbs, and boutique luxury lodgings like Hotel Leo.

But more than 120 years ago—before the days of commercial air travel, cars and the subsequent rise of motels (motor hotels)—Bellingham visitors arrived mainly by train or boat, and lodgings with individual bathrooms and electric lighting were considered newly modern conveniences.

There were many small, cheap places to hang one’s hat, but several hotels were regarded as more upscale facilities. These took in the affluent, and even the famous, at a time when the world moved slower than it does today.

Bellingham Hotel – 601 West Holly Street

Before the Bellingham Hotel occupied the Bellingham Towers, a previous iteration operated along the Bellingham waterfront where Chuckanut Brewery now resides.

Opened in 1889, the Bellingham Hotel was owned and managed by John Stenger, former head of the Colony Mill. Stenger made good money running the mill, but was so unpopular with mill workers that several of them eventually blew up his home with dynamite, according to Whatcom Museum archivist Jeff Jewell.

Seeking a more friendly industry, Stenger went into the hotel business. He also invested in the area’s first street car company, the Bellingham Bay Electric Street Railway.

The Bellingham Hotel sat at the off-ramp of Colony Wharf, requiring departed boat passengers to walk right by. This gave it an immediate upper hand over other local lodgings.

In 1895, Stenger built a 500-seat opera house onto the back of the hotel, further increasing its prestige. The hotel operated into the 1910s before becoming “The Ritz” in the 1920s. By the late 1940s, the structure had devolved into a sketchy tenement hotel, and was torn down sometime in the 1950s.

Sehome Hotel – 820 North State Street

Built around 1887, the Sehome Hotel served as decent lodging during the area’s mining days. The multi-story wooden structure was equipped with both electric lights and speaking tubes—the 19th century, non-electric equivalent of an intercom system. An advertisement in the 1905-1906 Bellingham directory called the Sehome a “first class family resort.”

It eventually became a residential apartment hotel, and burned due to arson in 1929. In its place came the Metcalf Dairy processing plant, which opened in the 1940s and eventually became a real estate office. Today, this building serves several commercial tenants.

Grand Central Hotel – Corner of North Forest and East Holly Streets

Among the area’s largest structures when it was completed in 1890, the Grand Central Hotel was built in anticipation of the Canadian Pacific Railroad. The railroad never arrived, however, and the Grand Central never opened.

In 1892, the wooden building became home to St. Luke’s Hospital, but the hospital used only a fraction of the place’s 100 or so rooms. St. Luke’s left after a year, and the building next hosted county fair exhibits and amusements from 1894 to 1895.

In 1905, the building became the Baker Hotel, after the entire three-story structure was lifted so a stone foundation and basement could be added.

Initially, the Baker hosted several conventions and business was good, but in 1910 the re-grading of Forest Street caused issues. Owner Maris Taylor attempted to sue the city for lost business, but was informed he’d moved his hotel a foot into the public right of way. He’d have to move it back, the city told him, for a legal challenge to succeed. In the end, his beef remained unsettled.

Taylor ran into financial trouble and closed the Baker around 1915. It was torn down in 1920 and its timber recycled for other uses. Today, its former site is occupied by the Community Food Co-op.

Hotel Henry – 1248 North State Street

Located in the 1907-built Exchange Building, the Hotel Henry opened in June 1923. Its owner and namesake was Henry Schupp, who’d operated Bellingham Bay Brewery with Leopold Schmidt, the late founder of Olympia Beer and namesake of the Leopold Hotel.

Schupp was manager of the Leopold during its glory years, and also helped to organize Bellingham’s Tulip Festival. The Hotel Henry had 100 rooms, half of which provided private baths and 30 of which had private toilets. In addition to gold-decorated mahogany furniture, the Henry’s four floors were adorned with beautifully framed drawings, pictures and photos. Several metropolitan shops existed on its lobby level, including a men’s clothing store, art shop, cigar stand, and jewelry store.

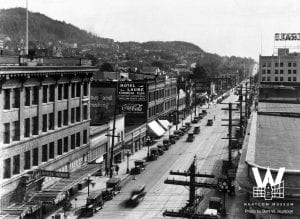

Outside, eight-foot-tall electric letters stood atop the roof, and a wrought-iron marquee hung over what’s now State Street. By 1924, a small automotive shuttle transported visitors of both the Henry and Leopold. In 1927, the Henry’s mezzanine became home to radio station KVOS. Broadcasting at 50 watts, the station’s studio featured a baby grand piano. KVOS operated from the Henry until 1932.

Amid the Great Depression, Schupp quit the hotel business and new management took over for 1934. That year, following the December 1933 repeal of Prohibition, the Henry became home to “Palm Gardens,” advertised as Bellingham’s largest beer garden. It operated until 1936, the same year Schupp died of a heart attack.

In 1942, the hotel property was sold to the YMCA for $22,500 (about $360,000 today), and any man with membership could, indeed, stay at the YMCA in a former Hotel Henry room. Although rooms are no longer rentable, the building has remained a YMCA ever since.

Laube Hotel – 1224-1228 North State Street

Built in 1903 at a cost of $12,000 (about $350,000 today), the Laube Hotel was constructed for owners Charles and Margaret Laube. It opened on February 3, 1904, shortly after Bellingham’s incorporation as a city.

The Laube had 51 rooms occupying two upper floors, built around a centrally located light well rising from the second floor through the roof. Light wells were common in buildings of the era, and can be found in other downtown buildings like the Daylight and the Countryman (now home to the Pickford Cinema).

The Laube featured craftsman woodwork and high-grade velvet carpets with various Persian and Asian designs. A ground floor café seated 80 people, with additional space for traveling salesmen displays. After about a decade, the Laube’s attraction faded, and it became a residential hotel through the 1970s.In the early 2000s, Jewell toured the Laube’s vacant upper floors, and says it has retained much of its original character, including large bathtubs.

Currently, the Laube’s upper floors are residential apartments, while its ground floor is occupied by Old World Deli and a thrift store. The upper left side of the building is still painted with signage from the hotel’s glory years, including an ad for Star Tobacco.

Fairhaven Hotel – Corner of 12th Street and Harris Avenue

Built by Fairhaven Land Company for over $150,000 (about $4.4 million today), the Fairhaven Hotel was the most opulent structure in 1890 Fairhaven. At the time, the town boomed with anticipation in being made the terminus of the Great Northern Railway.

The 100-room Fairhaven was considered among the finest accommodations on Puget Sound and the best in Whatcom County. Its five-story exterior—built of red brick and grey Chuckanut sandstone—was topped with a lookout tower and included architectural flourishes like Flemish gables, classical arches, and white-painted verandas with great Bellingham Bay views.

The hotel had a hydraulic elevator, gas and electric lights, fine oak furniture, gold-framed pictures, marble fireplace mantles, and served expensive, multi-course gourmet meals in its dining room. The one thing it didn’t have, though, was alcohol.

Just a month after its September 1890 opening, co-owner Charles Larrabee removed the hotel’s bar. His father had been an alcoholic who deserted his family, and Larrabee became a lifelong teetotaler. Co-owner Nelson Bennett sold his Fairhaven interest to Larrabee in 1891, and for a while the hotel flourished. But the Panic of 1893 formally ended Fairhaven’s business boom, and the Great Northern terminus went to Seattle.

In August 1895, Mark Twain stayed at the hotel after a lecture tour stop at the Lighthouse Theatre. Nursing a sore throat made worse by nearby forest fires, Twain was allegedly upset he couldn’t order a hot toddy of whiskey and water, and found refuge next door at the Cascade Club.

Larrabee’s liquor ban complicated deals to buy the hotel, as he rejected buyers’ plans if they included a bar. After being re-furbished in 1898, the hotel closed in 1899. Despite revival attempts in the early 1900s, the building mainly shifted to be the Larrabee family residence. All four of Charles Larrabee’s children, in fact, were born at the hotel.

Larrabee died in 1914, and his family moved to their new residence, Lairmont Manor, around 1918. In 1922, the Fairhaven housed a sanitarium promising to cure ailments with yogurt, and in 1923 became the Victoria Hotel. The Victoria closed in 1931.

Over time, the building was slowly stripped of its ornamentation, reduced to a drab but utilitarian structure. Its façade was covered in cement, and its tower and balconies were removed. By the end of the 1930s, by which time the county had purchased the building for a $1 deed and leased it to the Works Progress Administration, it was a three-story, flat-roofed structure.

The Fairhaven served as a community center for clubs, meetings and dances from the 1940s to the early 1950s. Following a dance in July 1953, an early morning electrical fire burned away the roof and gutted the third floor.

The county sold the condemned ruin for $1,200, and the Fairhaven was slowly demolished floor-by-floor. In January 1956, the final entrance arch to the building was knocked down. Over 100 truckloads of rubble were taken from the site and dumped in what is now Boulevard Park.

A gas station occupied the Fairhaven lot before being abandoned. Over time, the space held Christmas tree sales, art displays, food trucks and a used car lot. Although Fairhaven Towers, an apartment building constructed on the site between 2019 and 2020, includes architectural nods to the past, it can’t replicate the opulent artisanship the Fairhaven evoked for 1890s visitors.

“It’s the greatest building we’ve ever had in Whatcom County,” Jewell says. “It was whimsical, it was eclectic, it was just…wow. Once we had something like that, how could we ever let it slip away?”

The Sehome Hotel served many visitors during its late 19th and early 20th-century heyday. Photo courtesy Whatcom Museum

The Grand Central Hotel building served as a hospital, among other uses, before finally opening as the Baker Hotel in 1905. Photo courtesy Whatcom Museum

The Henry and Laube hotels along Elk (State) Street in the mid 1920s. Photo courtesy Whatcom Museum

The Fairhaven, which operated from 1890 to 1899, was among the most opulent hotels in the Puget Sound region. Notice the man standing atop the wooden power pole in this 1890s photo. Photo courtesy Whatcom Museum

John Stenger’s Bellingham Hotel was the first lodging choice disembarking boat passengers found upon arriving in the city. Photo courtesy Whatcom Museum