Photographs—moments in time, forever frozen with a shutter click—often bring the past to life in ways words cannot. Visual records of history are nostalgic to some, fascinating to most, and a pivotal part of Bellingham’s Whatcom Museum.

The museum’s photo archives hold more than 200,000 items, including collections from several prolific photographers whose local work accounts for tens of thousands of images. The preserving and organizing of these photos provide an invaluable resource for anyone wanting to glimpse our area’s past.

J.W. Sandison

Many of Bellingham’s now-iconic early 1900s images were captured by James Wilbur Sandison.

Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1873, Sandison moved west in 1899 to pursue commercial photography. After stints in Vancouver B.C., California and Hawaii, Sandison arrived in Bellingham in 1904. His earliest work used 6-by-8-inch glass plate negatives before a switch to film.

One of Sandison’s important contributions was capturing the first aerial photographs of Bellingham in 1912. The images were taken from a hot air balloon, and it would be another 16 years before anyone else captured the city from the air.

During the 1910s and ’20s, Sandison was a freelance photographer for the Bellingham Herald and other news periodicals. His photos were also featured in local school yearbooks. In 1931, he received national attention from American Photographer magazine for images of a northern Whatcom County limestone quarry.

In 1947, Sandison suffered a major setback during a 7,000-mile road trip to the East Coast with his wife. With no one watching his Bellingham studio, thieves broke in and stole more than $1,000 worth of cameras and equipment (nearly $12,000 today). After his wife died later that year, Sandison focused mostly on studio and portrait photography at his Holly Street studio. He never retired, dying at the studio in 1962 at age 89.

Whatcom Museum archivist Jeff Jewell says that because his offspring had no interest in retaining his father’s work, all Sandison’s photos were left to his somewhat overwhelmed studio assistant. The museum stepped in to purchase about 7,500 negatives dating from World War II and earlier, but passed on negatives from the 1950s and early 1960s because they were too recent. Many of those negatives and prints were either taken by individuals who wanted them, or simply thrown away.

When Jewell began working at the photo archives in the 1990s, he acquired four smaller, private collections of Sandison’s work, pushing the museum’s collection to around 10,000 original images.

Darius and Tabitha Kinsey

Darius Kinsey is world-renowned for his images of early Northwest logging and locomotives.

Born in Missouri in 1869, he came west at age 20 and settled in Snoqualmie, Washington. Kinsey bought his first camera a year later, took camera lessons from a woman in Seattle, and soon after began a career in photography.

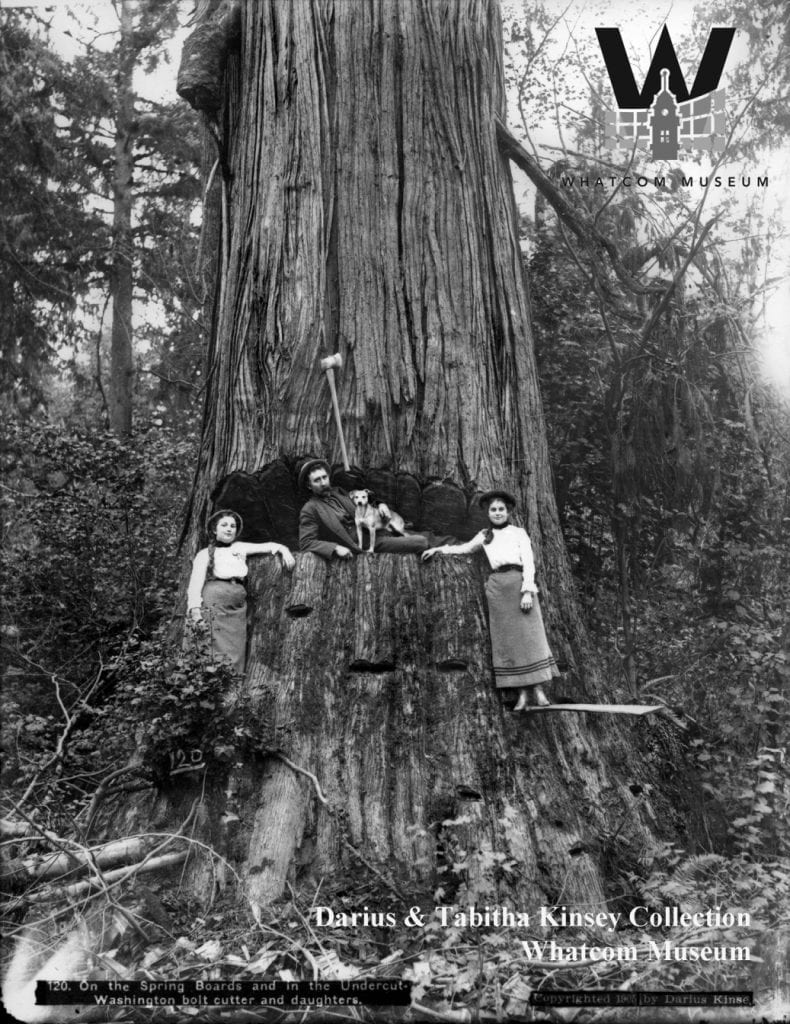

In 1894, he met Tabitha Pritts in Nooksack while working as a photographer in Whatcom and Skagit Counties, marrying her two years later. While Kinsey’s brother Clark went north to capture the Klondike gold rush, Darius and his wife built a Sedro-Woolley home that doubled as a portrait studio. Darius took the photos, while his wife helped develop negatives and make prints.

In 1906, they moved to Seattle and abandoned studio work, focusing solely on logging and scenic photos. Often hired by the companies whose operations he documented, Kinsey covered all phases of logging, from a tree’s first cut to its transformation into lumber. Many prints were sent back to logging camps so loggers could buy the images in which they appeared.

At some point, Clark returned from Alaska and the two brothers were unable or unwilling to work together. Clark took logging territory south of Seattle, while Darius claimed territory to the north. Darius retired from photography in 1940 after being injured in a fall from a tree stump. He died five years later. Both Darius and Tabitha are buried in Nooksack.

After his death, Tabitha sold his photos to a Seattle resident, where they stayed for 25 years before David Bohn and Rodolfo Petchek bought them, using the photos as part of a two-volume book about Kinsey published in 1975. Combined with a travelling exhibition of his work that debuted in Oakland around the same time, interest in Kinsey’s work greatly increased.

So much so, in fact, that Bohn and Petchek were once offered more than $1 million by advertising agencies hoping to alter his photos for product placement. The men declined. Over the years, Kinsey’s work has been published in books, used as cover art for novels, and exhibited around the world. Whatcom Museum bought the Kinsey collection in 1979. It consists of more than 7,000 original images.

Kinsey sometimes took risks to capture the perfect shot—including dodging avalanches, crossing crevasses and stepping past rattlesnakes. But he usually got what he was looking for.

“He never saw himself as an artist,” Jewell says of Kinsey. “I think he’d appreciate that people today appreciate his compositional skills.”

Bert Huntoon

Born in California in 1870, Huntoon is responsible for classic images of Chuckanut Drive, the Mount Baker Lodge, and other scenic Whatcom County locations. Working as an engineer, Huntoon first visited Whatcom County in July 1894 as an official of the Washington State Roads Commission. Tasked with finding the best route for a “Cascade State Wagon Road,” Huntoon and another man hiked along the Nooksack and Baker Rivers carrying 66-pound packs. Eventually, the men summited Mount Baker. Huntoon, armed with a Kodak camera, documented the month-long trip.

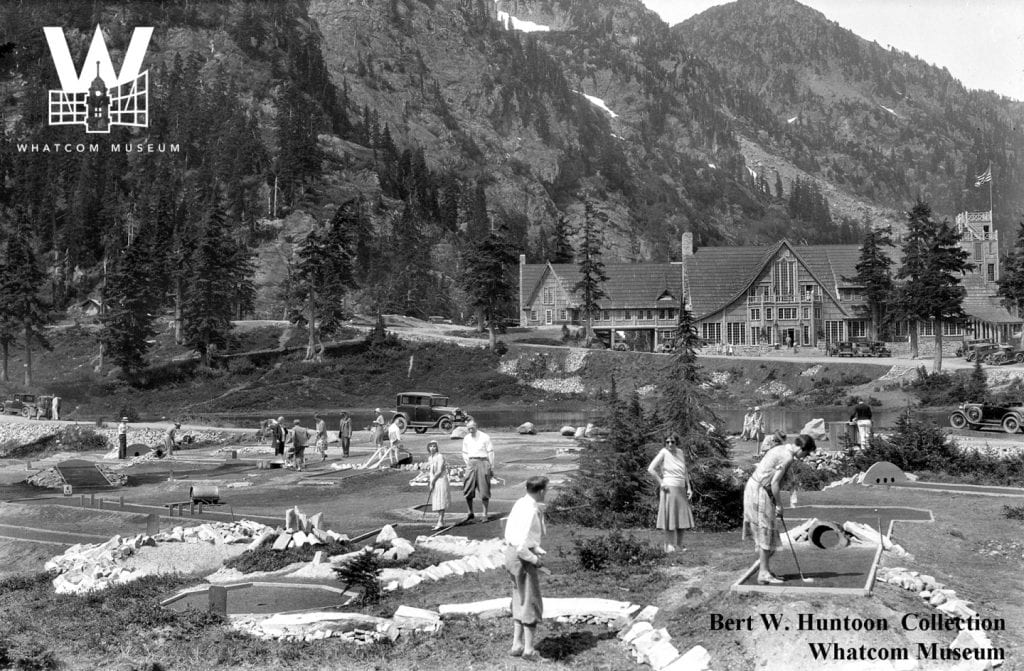

Huntoon become a county engineer in the 1890s before beginning a 45-year career with Pacific American Fisheries in 1899. Outside his employment, he helped form the Mount Baker Club in 1911—an organization whose mission was to bring recognition and tourism to the region. As general manager of Mount Baker Development Company in the 1920s, he was crucial in the construction of the Mount Baker Highway, Mount Baker Lodge and a park that’s now part of Sehome Hill Arboretum.

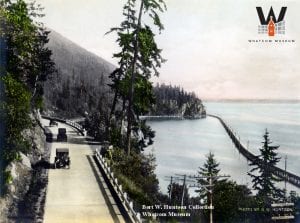

Huntoon was especially passionate about the building of Chuckanut Drive, and worked to have it included in the state highway system. Through all of his professional endeavors, Huntoon remained a devoted amateur photographer, often submitting his best images to publications that could help promote just how special Whatcom County was.

After his death in 1947, his photos were preserved by good friend and historian Galen Biery, who eventually gave them to the museum. Today, around 5,000 original Huntoon images reside there.

Jack Carver

The most recent photographer to have a substantial collection at the museum, Jack Carver was a lifelong Bellingham resident who served as a Bellingham Herald photographer from 1945 to 1981. At times, in fact, he was the paper’s only photographer.

The son of the Herald’s managing editor, Jack Carver began his journalism career as a paperboy in 1929. His photography interest began during Army Air Corp service in England during WWII, when he used a Kodak Brownie camera and sent home rolls of film.

After the war, he began in earnest at the Herald as a full-time photographer, capturing community events, breaking news, sports and all manner of daily Whatcom County life. In 1995, he donated his massive collection of images to the museum, and over the next 17 years helped Jewell catalog his photos with weekly visits to the archives. There are so many Carver images, in fact, that the museum has cataloged 54,000 of them and still isn’t finished.

Unlike many of Sandison’s photos, which required detective work because they often lacked dates or descriptions, Carver’s often had all the necessary info. And if one didn’t, Carver could usually figure it out from memory.

“He knew everybody,” Jewell says. “He had such access. Jack was everywhere, and everybody knew him. I miss him so, so much.”

Carver died in 2013 at age 95. Many of his photos remain nostalgic to long-time residents, some of whom remember last days of school, snow day sledding, the world’s tallest Christmas tree or visits from famous folks like Lyndon B. Johnson, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Carver’s images may be dated, but many of the elements they capture are timeless.

A Lasting Legacy

Today, the photo archives continue to serve as an invaluable resource to a wide range of people.

In addition to historical and personal research for writers, teachers, students and everyday folks, the archives have helped many local banks, restaurants, coffee shops and dental offices decorate their public spaces with historic prints.

“It anchors a community in time and just gives it a certain depth I think we’d be missing if we didn’t have those,” Jewell says of publicly displaying old photos.

Many images have also been licensed for use in books and other media; the museum has even helped Ken Burns, whose production company requested Kinsey photos for several of Burns’ acclaimed series, including “The West” and “Prohibition.”

Jewell considers cataloging and preserving these historic images a great responsibility, as well as a way of maintaining the photographers’ legacies.

“Without the photographers, none of this would exist,” he says. “We pass through this mortal coil, but there’s a reminder that we were once here.”

The Whatcom Museum Photo Archives are normally open Wednesday through Friday from 1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Check for any COVID-19 restrictions before attempting to visit.

Bert Huntoon captured this scene of folks playing miniature golf on the grounds of the Mount Baker Lodge in 1930. Bert Huntoon photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

Sandison captured this spectacular photo of downtown Bellingham from Sehome Hill in 1929. J. W. Sandison photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

Sedro-Woolley High School’s Gary Moon wins a high hurdle event during an April 1957 track meet. His teammate, Jeff Heverling, stumbled into the final hurdle but wasn’t injured. Capturing action shots with a 4×5 graphic camera—which didn’t shoot continuously—required a combination of luck and skill in those days. Jack Carver photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

The Kinseys ran a portrait studio from their home in Sedro-Woolley for several years. Darius took photos, while his wife developed negatives and made prints. Darius Kinsey photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

November 1921: This photo of a Charlie Chaplin look-alike contest is Sandison’s most famous, appearing in books, magazines and documentaries. The contest was organized by the Liberty Theatre’s manager to promote Chaplin’s film “The Idle Class.” Taken in the front of the theatre at 132 West. Holly Street, it is the only photo Sandison took of the contest. J. W. Sandison photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

Jack Carver captured this plane crash in Lynden on the morning of September 28, 1964.The plane’s carburetor froze on takeoff, causing it to crash land in the front yard of the Jones family at 8661 Benson Road. None of the plane’s four occupants suffered life-threatening injuries. Jack Carver photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

Huntoon was especially interested in the creation and promotion of Chuckanut Drive as a means to bring tourists to Bellingham. Note the interurban railroad trestle to the right in this undated image. Bert Huntoon photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

Kinsey poses with his equipment in 1920. Of the five cameras in this picture, two of them featured negatives sized 11 inches by 14 inches or larger. Darius Kinsey photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

This image of a Washington bolt cutter, posing with his two daughters on a massive tree, was taken in 1905. Kinsey was an in-demand photographer for capturing early Northwest logging scenes. Darius Kinsey photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Bellingham in January 1956 for speaking events and the christening of four-month-old Hall Randolph Walker. Roosevelt was the baby’s godmother. This photo was taken at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, and required Carver to use an intensely bright flash during the baptism. Jack Carver photo courtesy of Whatcom Museum