Whatcom County is a place lush with natural beauty and imbued with outdoor adventure. Today, it’s host to several recreational races representing numerous sporting endeavors. But long before Ski to Sea drew attention to the area, there was a race so dangerous and preposterous that it lasted only three years. It was called the Mount Baker Marathon.

‘Gateway to Mount Baker’

By 1911, Whatcom County was home to around 50,000 people, about half of whom lived in the growing county seat of Bellingham. There were reasons to visit the area (most of them based on work in trades like fishing, mining and logging), but tourism wasn’t among them.

With the addition of Mount Rainier to the National Park System in 1899, sentiment grew that Mount Baker and its surrounding area should be just as frequented by visitors, and perhaps also become a national park. In order to further those goals, many felt a noteworthy event was needed to publicize the area’s natural spoils.

The newly formed Mount Baker Club, consisting of local businessmen interested in showcasing the area’s beauty and resources, had an idea. Led by Arthur J. Craven, the club worked with the Chamber of Commerce to create a spectacle unlike any seen before. The idea allegedly developed from an argument: How fast could one travel from Bellingham to Mount Baker and back? Could it be done within 24 hours? Nobody knew the answer, because it had never been done any quicker.

Plans were made, and the result was a race unlike any held not just in Washington state, but in the entire country. At 10:00 p.m. on a mid-summer, full-moon night, racers would start in downtown Bellingham and run a short distance to one of two transportation options: a steam-engine train, which would take them 44 miles to Glacier; or one of several souped-up automobiles, which would take them 25 miles to a ranch outside Deming. Once racers reached their destination towns, they would run—mainly in darkness (so that sunlight wouldn’t melt any of the snow pack)—along their chosen trails to the 10,781-foot-tall summit of Mount Baker. There, judges would make them sign certificates and rest, for four full minutes, before beginning their return trip.

Once runners returned to Glacier or Deming (completing a round-trip of 28 or 32 miles, respectively; the Glacier Trail was shorter but steeper), they’d climb back aboard their transports and hopefully be the first to reach the Chamber of Commerce office back in Bellingham. The winner would claim the Herald Cup trophy and $100 in $20 gold coins (equivalent to about $2,700 today, with their weight in gold worth about $5,500). Whichever route the winner took would also give that town bragging rights and the attractive moniker of being “Gateway to Mount Baker.”

The Inaugural Race

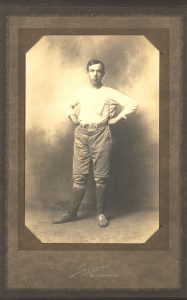

One by one, local men—all young and in prime condition—signed up to compete. Their occupations included farmer, logger, bed spring maker, milk inspector, and even insurance salesman. On the night of August 10, 1911, thousands of spectators attended the race’s start in downtown Bellingham.

As the Number 3 Special sped full-steam to Glacier at 65 mph, a handful of modified autos—many with their floorboards removed to save weight—drove just as fast over concrete and brick, wooden planks and, eventually, dirt roads filled with dangerous ruts. One car hit a pothole and split in half; its passengers escaped serious injury, but the crash ended their race.

Once the first racers began arriving in Deming and Glacier around 11:00 p.m., they ran into the darkness, gaining more than 9,000 feet at a pace they’d probably never experienced before. They also did so wearing heavy, cleated boots, a far cry from today’s engineered athletic shoes. Along the Deming route, several runners stopped for food and coffee at a couple’s cabin near the Nooksack River. Friends and family of some racers met them at the Mount Baker timberline, providing food and fresh clothing before they attempted the glaciated route to the summit.

The inaugural race came down to two men: Joe Galbraith, a logger, and Harvey Haggard, a mule packer at a local coal mine. Galbraith, 19, reached the summit of Baker 7.5 hours after the race began, in 70 mph winds and heavy snow, only to find he’d been beaten to the summit by Haggard 19 minutes prior. Another man, N.B. Randall, beat them both. Of the 14 men who started the race, only five summited Baker. While Haggard and Randall both made it back to Glacier, only Haggard caught the return train; race rules stated the train would leave one minute after the first runner hopped on, leaving Randall stuck in Glacier.

While Haggard rode the speeding train, Galbraith took Hugh Diehl’s fast Ford back to Bellingham. Haggard had the win in his sights until the train derailed, hitting a large bull that wouldn’t leave the tracks. Though shaken, nobody received serious injuries except for the bull; its carcass was later barbequed at a post-race picnic. Haggard, dressed in a bathrobe to stay warm after the derailment, took a horse-and-buggy to Maple Falls, then rode a horse to Kendall to get a car ride into Bellingham. In the end, Galbraith was the winner with a time of 12 hours, 28 minutes—far faster than anyone expected the winning time to be. Only four men finished the race.

Growth and Demise

The 1912 race featured much more fanfare and hype, and a $500 purse. There were hot air balloon rides and visiting U.S. Navy ships in Bellingham Bay. And this year, summit judges would use a telephone to relay race info to Bellingham.

Unfortunately, bad weather at Baker’s summit postponed the race by a full week. When it was finally run, only 9 men were at the starting line. Harvey Haggard, this time avoiding any bulls, won the race in 9 hours, 51 minutes. Near the finish line in Bellingham, a car without brakes plowed into a crowd of bystanders, seriously injuring a Civil War veteran.

In 1913, the race’s pomp and circumstance grew even larger, featuring the Barnum & Bailey Circus and tens of thousands of spectators. Racers from the East Coast participated. The race start was switched to 5:30 a.m. so people could see more of it. Race rules were also changed for fairness, making those who took one route have to take the opposite route back to Bellingham. But with another storm near Baker’s summit, the judges abandoned their posts, not realizing organizers had started the race anyway. The result was immense confusion. One racer—Paul Westerlund—encountered a judge who told him not to summit, and instead stop at the mountain’s saddle. Other racers weren’t so lucky, and with no warnings to turn back, went to the top.

On the way back down, Victor Galbraith, the 1911 winner’s brother, fell into a 40-foot-deep crevasse. Injured and only lightly dressed, he was stuck there for five hours before being rescued. Paul Westerlund won the race in 9 hours, 36 minutes, but controversy arose since Westerlund didn’t actually reach the summit. Second-place finisher John Magnusson, however, did. They eventually split the $400 prize.

As some people were unsatisfied with joint champions, a final “race for blood” was held in Glacier soon afterward. Racers ran from Glacier to Baker’s summit and back. Magnusson didn’t compete, but Westerlund and another man did. Westerlund won in six hours and two minutes.

Although there were plans to turn the 1914 race into a team relay event with three-man teams, the bad publicity from the 1913 event proved too much. With prominent businessmen like J.J. Donovan pulling their funding, the race became no more.

Legacy

Todd Warger is a local history author and producer of “The Mountain Runners”—a 2011 documentary on the Mount Baker Marathon that renewed interest in the mostly forgotten race. While it’s unknown how big the race could have been, Warger says U.S. involvement in World War I likely would have ended it anyway.

Today, Warger says the event should be remembered not only for its incredible story, but for being a founding father of modern adventure races.

“It was the first race of its kind in the United States,” he says. “This was before anybody knew anything about ultra-running; it wasn’t really a sport, per se. The perspective that people were looking at it [with] was entirely different. Towards the third year, they were calling it ‘human horse races,’ and they were doing it with disdain. It was so frowned upon that I think it got buried in history.”

Jeff Jewell, Whatcom Museum archivist, says the race’s legacy can be seen on several fronts. Tourist-drawing festivities for the race lived on in future events like the old Tulip Festival, Blossomtime Parade, and Ski to Sea. The event’s hot air balloon rides also led to the first-ever aerial photos of Bellingham. And although Mount Baker never became a national park, the race was successful in touting the area’s recreational opportunities, which led to the popular Mount Baker Lodge of the 1920s.

The event’s adventurous spirit lives on today with the Ski to Sea race, the world-renowned multi-sport relay race that begins at the Mount Baker Ski Area and ends in Bellingham. The Mount Baker Ultra, an annual 56-mile run from Concrete to Baker’s Sherman Peak and back, is an even more direct descendent.

“It’s an event that was way ahead of its time,” Jewell says of the Mount Baker Marathon. “I think people today romanticize it, and that’s great. They should romanticize it.”