Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, plunged the United States into war just as the holiday season was beginning. As the war dragged on for four long years, people in Bellingham found ways to come together to celebrate and to support those in the military who were far from home during the holidays.

Helping Soldiers

The American Legion collected gifts at their hall to give to soldiers that first wartime Christmas. Those who wanted to invite soldiers to join the family dinner were asked to call the local armory and not the “Filter Center,” whose phone line was reserved for air raid warning use only. Many service members could not get leave on Christmas, as the country was on high alert for possible further attacks.

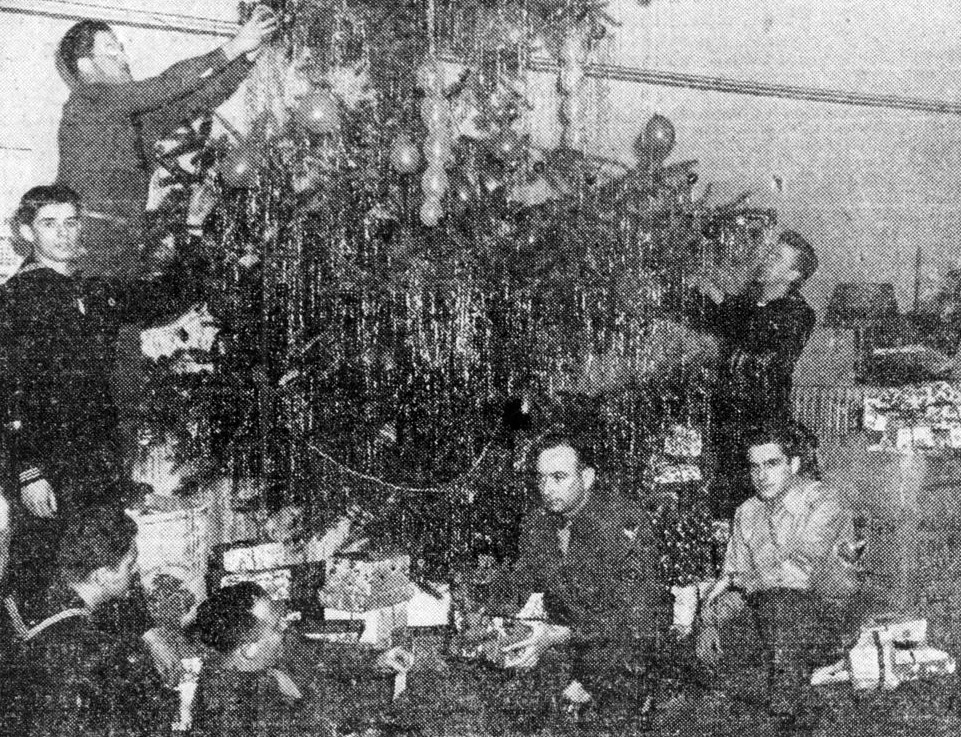

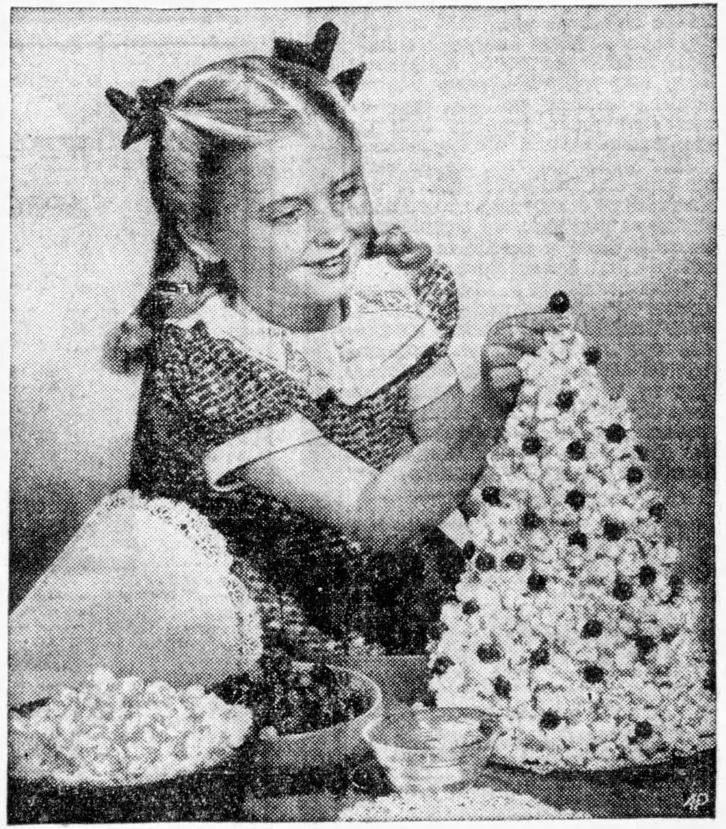

As the war progressed, efforts to help soldiers became more organized. A USO Hospitality Center for service men and women was set up on East Holly Street. Servicemen, their wives, and servicewomen could go there for rest and entertainment throughout the week. In 1942, the junior hostesses put on an informal, “homey” party, serving a buffet supper on Christmas day. City and county organizations donated the food. High School students cooked up cookies and candy while the Camp Fire Girls made 100 popcorn balls. Volunteers also handed out gift boxes prepared by county and local civic organizations.

Others rushed to mail packages to their loved ones in the military. They were encouraged to mail in October to ensure arrival in time, even earlier for Hannukah. The city residents sent record-levels of mail. On October 16 alone — the 1943 deadline to send gifts to soldiers overseas — the city sent three tons of packages to service members overseas, as well as sacks upon sacks of cards and letters. The local Salvation Army sent hundreds of gift boxes to soldiers who otherwise would receive no holiday presents.

Besides gifts, the holidays were a time to donate to the Red Cross and buy war bonds. “Send gifts of tanks, guns, and planes to our boys with a war bond in every stocking,” urged a 1942 Puget Sound Pulp and Timber Co. ad. “The very best wish we can think of,” proclaimed a Lee Grocery ad in 1943, “is that by Christmas, 1944, the Axis will be completely licked and then there will be everlasting peace throughout the world.”

But for many during the war, their loved ones were far away from home, their fates uncertain. Soldiers celebrated in bases across the country, on ships, hospitals, prisons, and on the front lines. For many, there was no holiday at all.

Said former army medic Corporal John Aubert when interviewed in 1945, back home in Bellingham, about the Christmas the year before: “I worked so bloody hard that day, fixing up casualties from the night before [from the attack on Morotai island], that I went to bed early” after having a bit more spam than usual.

For fellow Bellingham-native Arnold Donnovan, leading a platoon clearing mines at Odgivilla, Christmas 1944 meant a cake baked for his group by a German family in the ruins of their shelled-out home where the soldiers were staying.

Holidays on the Homefront

Back home, people tried to continue celebrating the holidays as close to normal as possible, although gasoline rationing and limited train availability made traveling to see family impossible for most. People held church services, holiday concerts, craft fairs, “white elephant” auctions, parties, and dances.

People on the homefront were confronted with rationing and shortages. Toys used wood, cardboard, and “non-essential” plastic instead of metal and rubber. Enterprising grandma Mrs. B. F. Nicolay decided to make a dollhouse and a Noah’s Ark with toy animals for her grandchildren.

Local newspapers were full of ideas of how to bake for the holidays in accordance with rationing and shortages. “Candy, this holiday season, is hard to come by,” wrote Associated Press Food Editor Charlotte Adams in 1944, “but there are certain simple confections you can make at home” to uphold holiday traditions. Sugar-saving recipes used things like corn syrup, honey, and molasses to replace or reduce the use of rationed granulated sugar.

Other suggested recipes included treats to send to loved ones in the military. These had to be things that could “take it,” like cookies, fruit cakes, hard candy, dried fruit, and carefully packed jars of homemade jam.

Closer to home, people baked for soldiers nearby. In December 1941, Fisher’s Blend Flour sponsored a weekly “Cookies for Rookies” contest through local grocers. In one week alone, 88 dozen cookies were sent to Fort Lawton, 35 dozen cookies were sent to the British warship Warspite anchored in Bremerton, as well as many more to the service men’s clubs locally.

Peacetime Christmas

The holiday season in 1945 was a special one. The war was finally over! While many soldiers had yet to return and the difficult work of rebuilding loomed ahead, people welcomed the holidays with new joy. “Merry Christmas to all those still in service,” a Forrest Furniture Manufacturing Company ad proclaimed, “and those who are at home and to every civilian in America. May we keep America a land of justice and freedom for all years to come.”