Mount Baker, the North Cascades stratovolcano named Komo Kulshan in indigenous languages, has become a prominent symbol of life in Bellingham. It features in the logo for Western Washington University, which has defined Bellingham as a college town since 1893. With over a century of university activity on the peak, however, this connection is just the tip of the glacier.

In and out of class, Western students and alumni flock to Heather Meadows, Artist Point, and surrounding Mount Baker Wilderness. The peak is famous for record snowfall and standing in for Alaska in the 1934 film adaptation of Jack London’s Call of the Wild.

Throughout the university’s history, Mount Baker has been the site of countless adventures, a tragic mountaineering accident memorialized on campus, and scientific research that continues to this day.

Kulshan Cabin

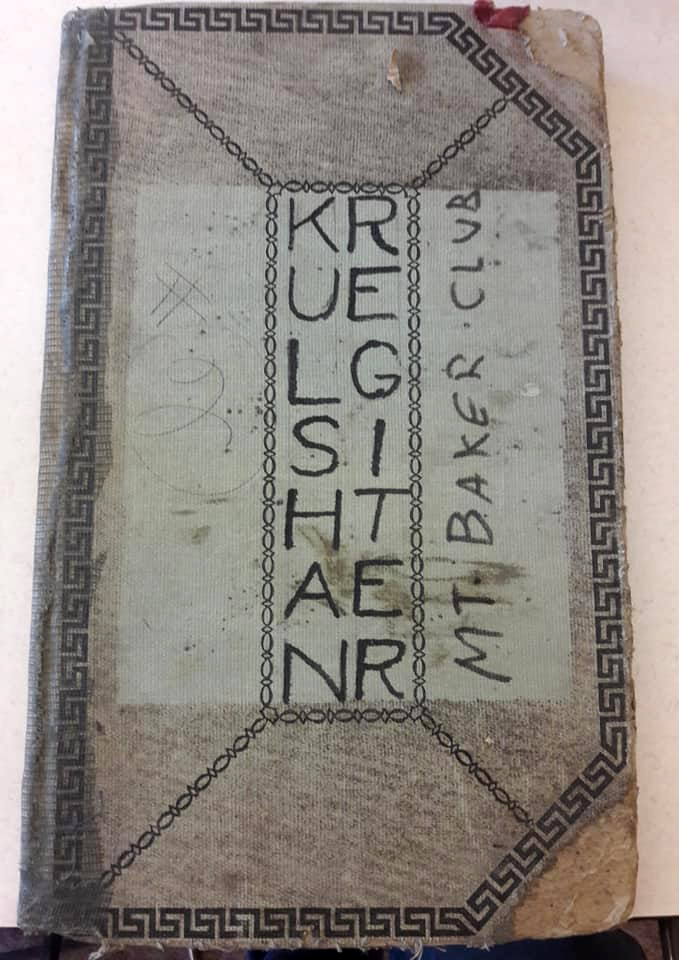

WWU shares its early mountaineering history with Mount Baker Club, a community organization dating back to 1911. The club sponsored the Mount Baker Marathon, which enchanted recreationists with the prospect of summiting the peak. In 1925, Mount Baker Club built Kulshan Cabin — a Glacier outpost that Western’s Associated Students would jointly own after it was rebuilt in 1949.

A Mount Baker Club log entry dated December 27, 1925, notes the “first successful ascent from this cabin” and “first successful mid-winter ascent ever made to the summit.” Meanwhile, Western students and faculty took annual summit hikes for decades before jointly owning Kulshan Cabin. The cabin remained until the 1980s, when new roads and lodges had rendered it obsolete.

The CPNWS archives Kulshan Cabin registers from 1925 to 1972 and logbooks from 1976 to 1984. Students logged stories of their expeditions, contributed drawings and poetry, and commented on then-recent events such as the early LGBTQ+ movement, peace protests, D.B. Cooper incident, and Mount St. Helens eruption. One cover page’s handwritten note refers to the university’s biggest tragedy: “Some members of this climb were killed on Baker the following year 1939.”

Mount Baker Memorial

On July 22, 1939, a WWU expedition to Mount Baker became the era’s worst mountaineering accident in American history. Six climbers in a group of 25 lost their lives in an avalanche, which survivors described as a current pulling them under. Four of the victims’ bodies were never recovered in ensuing searches.

University President Charles Fisher held an assembly with student services for the victims. (This was Fisher’s last term after the notorious Red Scare-influenced committee hearing that cost him his job.) Fisher’s comments state, “Although none reached the summit of the mountain, their indomitable spirits triumphed in disaster whether they survived or perished.”

Similarly, Charles Edward Butler’s poem “Requiem” from WWU publication The Collegian concludes: “Goodbye: the dream endures. You will be young forever: the heights will be forever yours.”

By spring 1940, a Mount Baker Memorial Committee started to collect donations for a monument. They proposed a design that would blend into the campus’ landscape using basalt rocks from Mount Baker and alpine shrubs. Landscape architect Noble Hoggson and sculptor Dudley Pratt completed the memorial several years after the disaster due to logistical issues. Today, it still stands guard to the climbers’ memory outside Edens Hall and Old Main.

Washington State Poet Laureate Ella Higginson, who lived in Bellingham, wrote “A Sepulchre of Snow” to memorialize the 1939 avalanche victims. The final verse concludes: “Through the ages to be identified with one of the most beautiful mountains known; to lie there forever, on the silver crest of the world, close to God — my brothers, do you know anything lovelier after death than this would be?”

Western’s Volcanology

Mount Baker has also been a hub for the university’s scientific research for decades.

Throughout the 1970s, geologists observed seismic activity and steam (including “spectacular fireworks” on New Year’s Day 1977). Speculation ran rampant about potential eruptions. Dr. Don J. Easterbrook’s influential 1975 publication “Mount Baker Eruptions” noted the risk of meltwater floods into Nooksack and Skagit Rivers, should an eruption occur.

Western’s archives document news clippings and geological essays from the period. Although Mount Baker has not erupted since 1880, an August 1975 snippet from “Etc. News” titled “Mount St. Helens next to blow?” called it “one of the U.S. volcanoes most likely to erupt.” On March 27, 1980, Mount St. Helens erupted with the force of 1,600 atom bombs — devastating the immediate area and spreading ash around the globe. “Makes Mount Baker seem like a fire cracker,” the report presciently quips.

Today, students in the fields of geology, glaciology, biology, and forestry visit and study Mount Baker Wilderness. Science Mathematics and Technology Education (SMATE) has used the volcano as a natural field laboratory to study eruptions and design emergency responses. Still other students have climbed, hiked, skied, and snowboarded at the mountain for outdoor “experiential education.”

Whether in the sciences, arts, physical education, or recreation, Western continues a history as old as the hills.