On June 14, 1968, a Bellingham woman known as Joy Stokes died at age 73. In her will, she left an alleged six-figure sum not to surviving family, but to Western Washington University.

Stokes had owned several apartment complexes in Bellingham, and also managed a lively roadhouse just beyond the city limits. Even so, it seemed a large amount of money for someone who came from modest means.

Both among her family and the community, it was said that Stokes’ wealth was amassed not through real estate, but from prostitution work as a madam. There was even a rumor she was possibly responsible for the death of her ex-husband.

Her story is one of intrigue, mystery, and an ultimately enduring legacy of helping others.

Red Lights and Rough Reputations

While modern Bellingham is rife with breweries and dispensaries, it once boasted a real red light district. Even before the city’s incorporation, the towns it was formed from allowed prostitution to occur.

In his 2004 book “The Brothels of Bellingham,” author Curtis F. Smith writes that the earliest known prostitution rooms were waterfront shacks along Whatcom’s tide flats. Its 1901 city charter even established boundaries for a red-light district.

Starting at the intersection of Holly and Bay Streets, and continuing down Holly to C Street, brothels stood catering to lonely or randy men, many of them transient workers attracted to the area through industries like logging.

In Fairhaven, the area below 12th Street became so infamous it was referred to as “Devil’s Row.” And for a time around the turn of the century, a small red book was published for male visitors, informing them of local “sporting houses.”

Social pressure brought a 1910 crackdown on Bellingham’s original red-light district, but it did little to stop prostitution. Until around 1950, downtown Bellingham was home to brothels, many located on the upper floors of cheap hotels and apartments.

Smith’s book reveals at least 13 known brothels in Fairhaven, with another 14 having existed throughout downtown Bellingham’s history.

A Lady Comes to Town

Joy Stokes was born Mary Elizabeth Thomasson in 1894 West Virginia, the middle of seven children. In 1907, her family moved west, settling in Fairhaven’s Happy Valley neighborhood. Thomasson worked at Fairhaven’s Pacific American Fisheries cannery as a teenager, losing part of a finger in an accident that caused her father to sue PAF. It’s unknown what settlement, if any, resulted.

In December 1916, Thomasson married lumber inspector Roy Stokes and legally changed her name to Joy Mary Stokes. In the decade that followed, both Mary and her family became local scofflaws.

Her father operated a still hidden inside a chicken coup, and her brothers also engaged in bootlegging. Harry, a brother known as “Society Red,” eventually fled Bellingham for Canada’s Northwest Territories, evading bootlegging charges and the World War I draft. He spent most of his life there as a fur trader.

“The whole family was a little bit scandalous,” says Kristine Kincaid, a 73-year-old Bellingham resident who is Stokes’ grandniece.

During the 1920s, Stokes was charged with larceny for allegedly stealing another woman’s lingerie. She was also part of the 1929 divorce trial of William Lang, a man who supposedly financed the impressive home Stokes and her husband lived in at 415 North Forest Street.

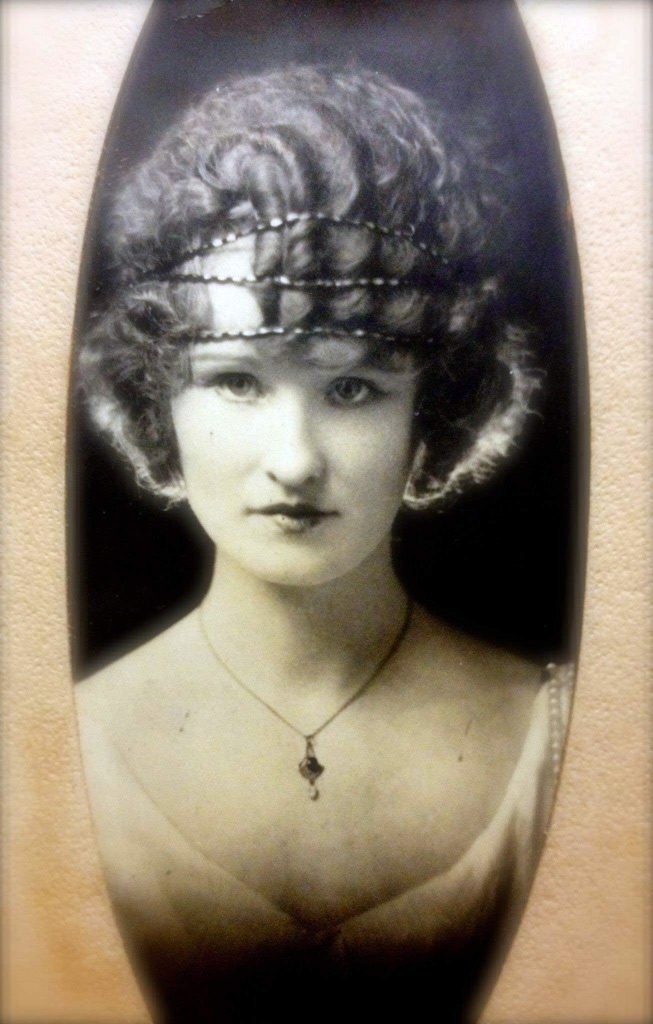

During the trial, Lang’s wife testified that he’d been enamored with Stokes — an often elegantly-dressed redhead — for years.

While the Lang marriage crumbled, Stokes and her husband remained married until 1943.

Known Unknowns

Kincaid says she and siblings knew Stokes as “Aunt Jane,” a brusque older woman they saw only around Christmas.

They knew she had a prosthetic leg — the result of a car-related accident years earlier — but didn’t know much else about her. Becoming aware of her great-aunt’s illicit occupation didn’t follow until around high school.

“My mother, she’d kind of talk around it,” says Kincaid. “We were aware that we had an aunt who was a madam, but we never got a lot of details.”

Kincaid has no concrete evidence proving Stokes was a madam, but based on family lore, she’s 100 percent certain it’s what her aunt did. Likewise, Bellingham historian Kolby LaBree has never found arrest records or other legal documents confirming Stokes’ profession. But there are hints.

Despite Stokes’ husband not being well-off, the couple lived in nice homes around Bellingham, moving roughly every three years through the 1920s and 30s. Kincaid says Stokes owned some of Bellingham’s first modern household appliances, and frequently dressed like someone who lived in a much bigger city than Bellingham.

Stokes did well for herself after divorcing her husband. She owned and managed the Verna Vista Apartments, a complex at 701 Gladstone Street that still stands today, and also acquired the El Sereno Apartments at 715 Garden Street in 1948.

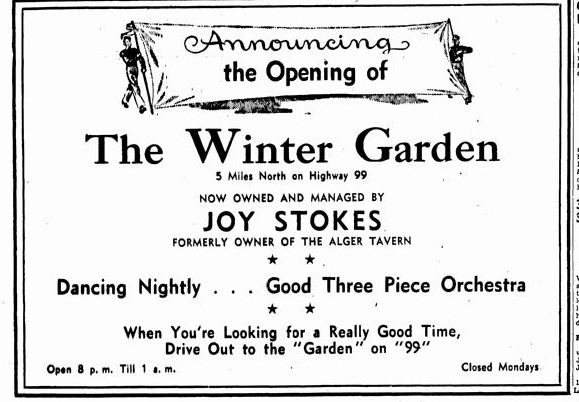

That same year, she began managing the Winter Garden, a post-Prohibition roadhouse located five miles outside Bellingham, where Slater Road intersected Old Highway 99.

The Winter Garden had live music, dancing, and drinking, but it was rumored Stokes ran a brothel upstairs. Kincaid says a brothel definitely existed there, while LaBree says her research is inconclusive. The Winter Garden did, however, have underage serving issues and garnered a liquor license suspension.

It’s possible that Stokes also conducted prostitution at the properties she owned, but this is also speculation. In any case, there’s little doubt Stokes stood out: oral history interviews in Smith’s book refer to her as a “redheaded woman who wore lift brassieres.”

History’s Mysteries

On April 4, 1951, Stokes’ ex-husband and his girlfriend were found dead in a basement apartment of the El Sereno. A detective who discovered the couple said the apartment was full of gas fumes, with a small gas heater still burning. Both victims appeared to have been asleep. There was no suicide note.

A Bellingham Herald article says Stokes was extremely upset about the tragedy, but Kincaid says some family members questioned if it was really just an accident. Stokes’ diaries indicate Roy was an abusive drunk, once threatening to have her killed. He was also out of work at the time and may have resented his ex-wife’s financial well-being.

“Nobody really knows,” Kincaid says.

Another question about Stokes remains unanswered: how she grew estranged from her family, ultimately leading to her generous posthumous donation to WWU.

Most of the Thomasson siblings had no children, including Stokes. The siblings that preceded her in death left her nothing, and she in turn left nothing to those who survived her. Kincaid says she doesn’t know why the estrangement occurred or whether it was over her being a madam, but it was never resolved.

Stokes sold the Winter Garden in August 1959, several years after a 1955 fire left it in shambles. Rebuilt under new ownership, it continued into the 1970s until being demolished for construction of the Slater Road overpass above Interstate 5.

Lasting Legacy

Stokes never remarried, but her diaries indicate male companions moved in and out of her life.

Kincaid says one of these men, a younger gigolo, may have talked Stokes into leaving her money to WWU and in return got something out of it. Another theory, LaBree says, is that she left money to help students because she once employed female students — trying to pay their way through school — as working girls.

Regardless, her last wishes were carried out, and today the Stokes Scholarship is one of WWU’s longest-running endowments. Each year it provides needed dollars to deserving students who might otherwise be forced to take loans or drop out altogether. Managed by the Western Foundation, it will continue on indefinitely.

Now the same age her great-aunt was when she died, Kincaid has poured over Stokes’ old pictures and diaries. The last direct links to her long-gone, she wishes she could speak to Stokes again.

“I would love it if I could know her now,” Kincaid says. “I have a feeling there was a whole lot more substance to her than just being a madam.”