Since its township beginnings, Fairhaven has been defined by many colorful characters whose biographies blend fact and fiction. Founder “Dirty Dan” Harris’ birthplace and date are notoriously uncertain, and his exploits are among many others’ that have earned Fairhaven its early “wild west” reputation. But one standout eccentric cemented local and national legends in only a few years: investor and self-proclaimed cat rancher James Wardner.

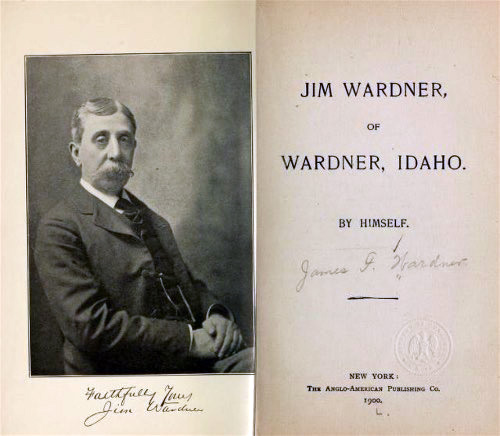

Born in 1846 in Milwaukee, Wardner invested in mines across the country, starting 1871. He rapidly gained and lost fortunes throughout booms and busts, even naming two boomtowns after himself in Idaho and British Columbia.

In 1889, Wardner arrived in Fairhaven at promoter Nelson Bennett’s urging. He started Fairhaven Water Works Company, Samish Lake Logging and Milling Company, Fairhaven Electric Light Company, and Cascade Club. Wardner opened Blue Canyon Mine in 1890, selling it in 1891 with J.J. Donovan and Julius Bloedel managing. He left for South Africa in 1893, briefly returning between other investment schemes.

Wardner developed a reputation for whimsy. His 1900 autobiography describes his first venture as selling a rabbit’s young when he was just eight years old. Contemporary readers speculated that he inspired Mark Twain’s Mulberry Sellers. Today, Fairhaven remembers Wardner for a feline-themed hoax that made national headlines and a house of local legend.

Herding Cats on Eliza Island

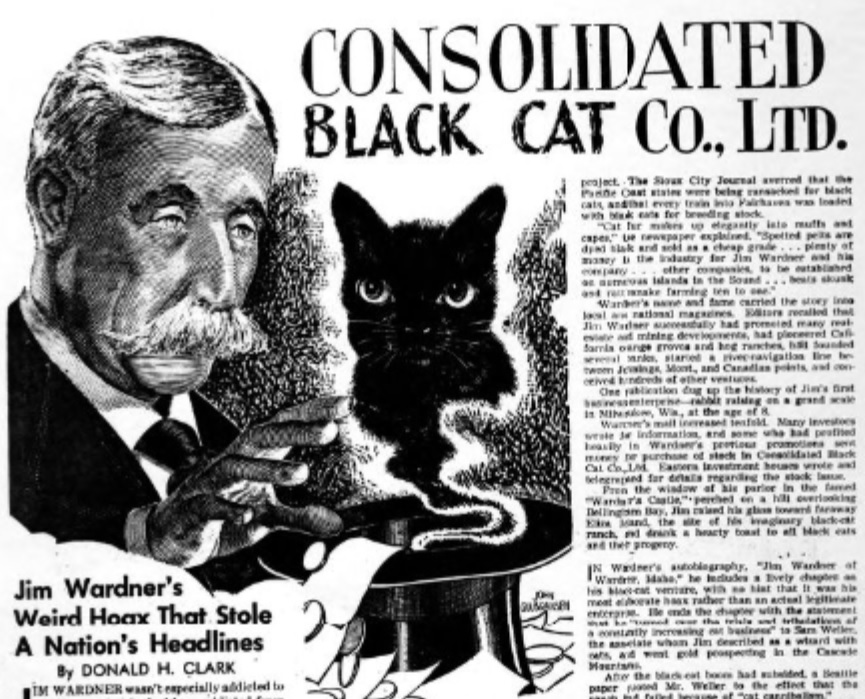

James Wardner’s cat tale started in 1890 when Fairhaven Herald reporter E.G. Earle approached him in search of a story. With characteristic good humor, Wardner said he planned to raise thousands of black cats for their pelts through his latest venture: Consolidated Black Cat Co., Ltd. He claimed to own an Eliza Island ranch run by Sam Weller — a fictional character in Charles Dickinson’s The Pickwick Papers.

The story made the Fairhaven Herald’s front page news. Due to Wardner’s national notoriety, editors reprinted it from San Francisco to the New York Tribune, which ran the headline “Black Cats for Profit.” Successive stories claimed that investors sent money, which was eventually returned to them — literally putting stock into the tale.

Journalists embellished the story with details of cats living on local fish, wandering the island freely, and lending their pelts to capes, muffs, and plaster. Wardner kept playing with his cat yarn as it unraveled nationwide, reprinting news stories in his autobiography with tongue-in-cheek acknowledgement.

He wrote of the cat ranch and its reputation: “the product did not equal my anticipation.” Indeed, without disclaimers on its veracity, the hoax blurred the lines between satire and sincerity in the public’s beliefs.

The black cat story took on a life of its own (or perhaps nine) in Fairhaven’s community. It inspired residents’ adoption of real strays rumored to descend from the ranch cats. Informal volunteer group “Fairhaven Kitty Committee” built homes for strays through the last few decades of the twentieth century. Mason Block, which hosted Wardner’s office and Cascade Club, is now Sycamore Square and home to restaurant The Black Cat (Le Chat Noir).

Haunting Castles

In 1890, the same year James Wardner created his cat story, he built a mansion whose local legacy would outlive him. “Wardner Castle,” so nicknamed for its opulence, still stands tall on the corner of 15th Street and Knox Avenue.

Spokane architect Kirtland K. Cutter designed the Queen Anne-style house alongside local architects Longstaff and Black. Its three stories contain 23 rooms. Original features include fireplaces with carved wood mantelpieces, stained glass windows, and a porte-cochere that overlooks Bellingham Bay and the Puget Sound.

Wardner’s family lived in the house for just one year. Puget Sound Mills & Timber president John Earles lived there with his family until the 1930s. Wardner’s Castle became restaurant Hilltop House from 1947 to 1955, then a private residence, and Wardner’s Castle Museum from 1983 to 1986. The last tenant was Castle Gate House Bed and Breakfast, active from the 1980s through 2000s.

The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. Today, it is privately owned.

WhatcomTalk has previously noted Wardner’s Castle’s reputation as a haunted place. Most local legends revolve around “Spirits of Wardner’s Castle,” a 1984 mural painted inside by local artist Laurie Ann Gospodinovich. The mural depicted Wardner, the castle, Fairhaven landmarks, and black cats alongside a ship bound for Eliza Island. Gospodinovich died at 24, only a few months after finishing the painting, and had painted another mural for La Creperie in 1983. Both murals have disappeared: Castle owners repainted, and a 1987 arson destroyed La Creperie — now The Black Cat.

Through the house’s local intrigue, Wardner’s spirit of mythmaking lives on.

Where Are They Now?

James Wardner died in 1905, bearing a simple headstone in Milwaukee. However, he ended his autobiography requesting that his epitaph read: “Oh, where, and oh, where has Jim Wardner gone? Oh, where, and oh, where is he? With his tales of gold and his anecdotes old, And his new discover-ee?”

Wardner Castle awaits new uses. After a century of renovations, it has been painted turquoise green, then purple, and finally blue.

No remains of Wardner’s black cat ranch on Eliza Island have ever materialized. But these local familiars continue to cross paths with Fairhaven, running wild in the realm of imagination that Wardner set free.