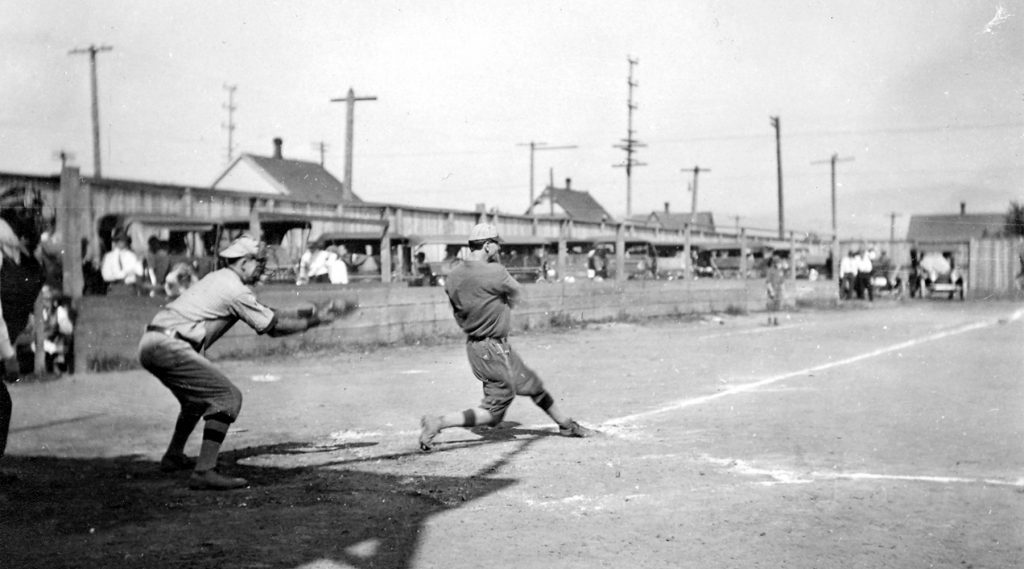

When it comes to local baseball, today’s Bellingham residents can check out a Bells game at Joe Martin Field, softball and recreation league match-ups at several city facilities, and high school games at various district diamonds.

But once upon a time, none of the city’s current baseball venues existed, and residents filled places long since erased from the map. Here are some noteworthy ballparks of Bellingham’s past.

Fairgrounds Field (1901–1912)

During the 1880s and ’90s, Bellingham’s annual fair was held on cleared land that’s now industrial property just north of Iowa Street. In 1899, the City of Bellingham obtained a one-year lease on the land as a gift from its owner, the Bellingham Bay Improvement Company, to use for sporting festivities for as long as the company owned it.

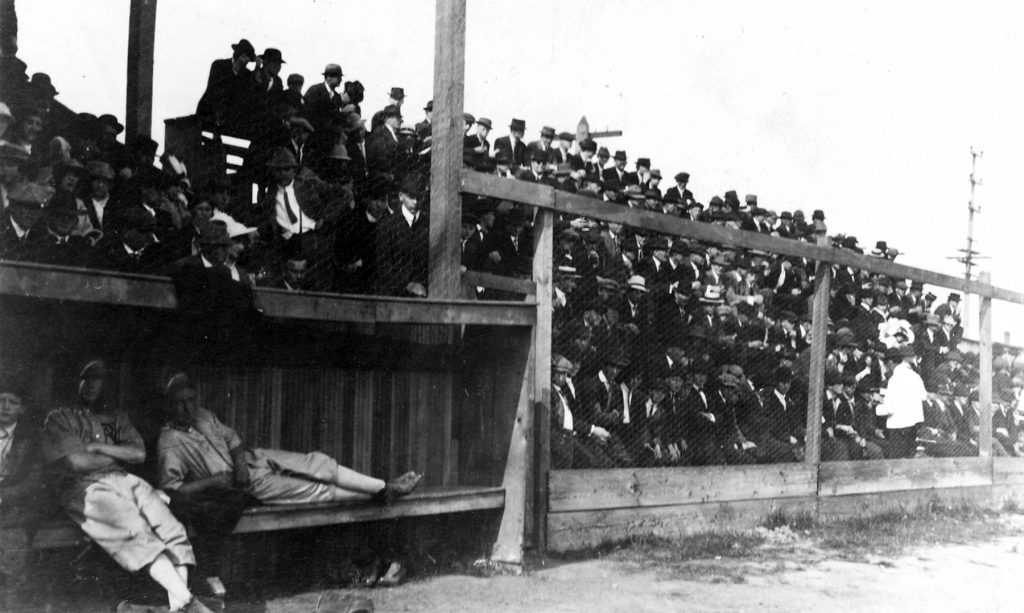

By 1901, the grounds had a half-mile horse track and a 200-foot-long, covered wood grandstand — situated on the track’s straightaway — that could seat more than 2,000 people. Baseball was played in the track’s infield. High school games took place here, as well as home events for teams formed by the Whatcom Athletic Club, Bellingham Bay Brewery, and Whatcom Baseball Club.

In 1905, Bellingham’s first professionally organized baseball team, the Bellingham Gillnetters, played home games at the fairgrounds diamond. On opening day, many local businesses closed so workers could attend, schools dismissed students early, and more than 3,500 people reportedly packed the facility.

The Gillnetters had some devout fans, including the “Cowbell Gang” — 10 businessmen and bartenders who each held a cowbell with a letter on it. When lined up, the bells spelled out “BELLINGHAM.” The gang enthusiastically rang their cowbells, especially when trying to distract the opposing team’s batters.

The Gillnetters also had standout pitcher Carl Druhot, who’d go on to play for the Cincinnati Reds in 1906. Druhot had a brief major league career but earned strikeouts against star hitters like Honus Wagner.

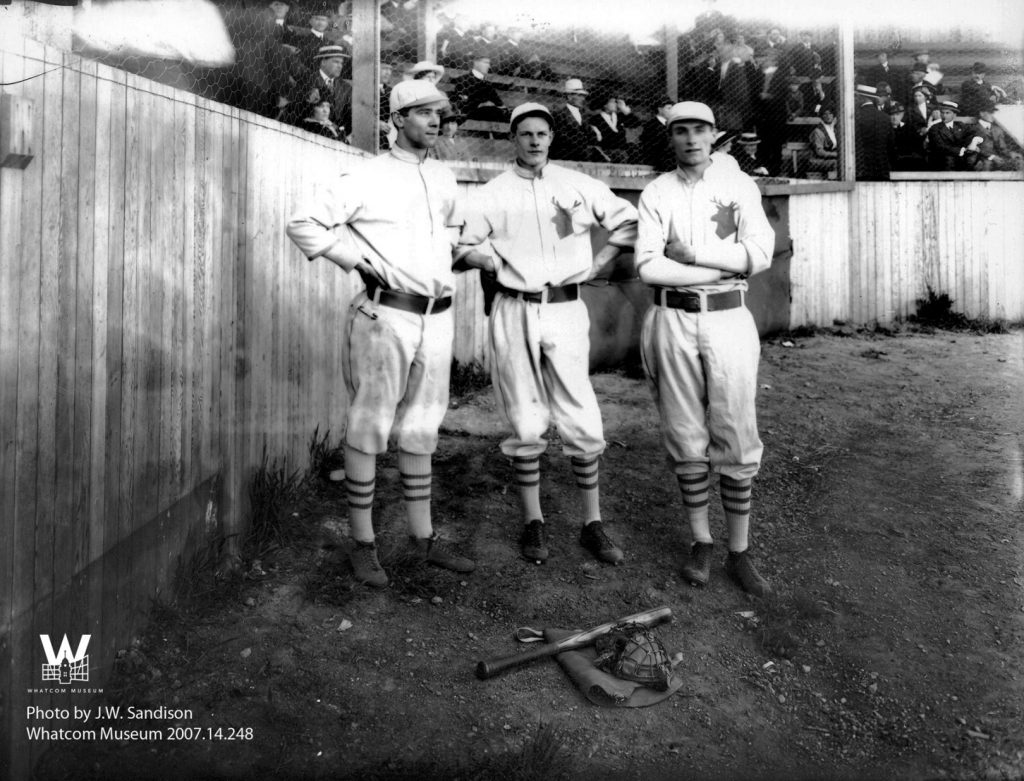

Unfortunately, the Gillnetters struggled on and off the field, folding after just one season. The fairgrounds later hosted a city team, the Bellingham Regulars, from 1907 to 1910, and the semi-professional Bellingham Elks in 1912.

Still, the fairgrounds were never truly suitable for baseball. Despite ideal trolley line access, the field had no fencing and seating only ran down the third base line, making for poor sightlines.

The approximate location of the baseball field today is where Nevada Street runs between the Puget Sound Energy recycling center and the Brooks manufacturing plant.

White City Ball Park (1907–1910)

The Silver Beach Amusement Park, which opened in 1907 on the shores of Lake Whatcom, featured a roller coaster, Ferris wheel, and dance pavilion, among other attractions. It also included a large, grassy field used for picnics, expositions, dirigible demonstrations, and baseball games.

The field was primarily used for high school games through 1910, but after that it apparently held more picnics than ball games until the amusement park closed, sometime between 1918 and 1919.

The former ball field remained vacant for an unknown time before being developed. Today it’s the location of residential homes in the Silver Beach neighborhood, and Northshore Drive wraps around what was once the field’s northern and eastern boundaries.

Elks Field (1913–21)

Located where Kentucky and Ellis Streets meet, Elks Field was built in 1913 to be the home of the Bellingham Elks, the official city team at the time.

The fenced-in ballpark was constructed following a multi-year agreement between George Downer, the Elks’ manager, and the Bellingham Bay Improvement Company, to build a half-circle grandstand at a cost of about $1,000 (roughly $29,000 today).

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Elks Field — and one that shows up in several photos — was its automobile entrance at the park’s northeast corner. This allowed spectators to watch games from the comfort of their own vehicles along the first and third base lines, and do so while protected from foul balls by a metal screen.

Whatcom High School used the field for baseball, as did Western Washington University. Barnstorming teams from out of town also frequented the diamond, and school kids held various athletic contests there.

Elks games were extraordinarily popular in the mid-1910s, drawing crowds of up to 2,000 people. Opposing teams sometimes hailed from outside of Whatcom County, including Canadian teams and Seattle-based Japanese teams like the Nippons.

The Twilight League formed in 1919, with local teams engaging in summertime, evening play at the park, which was renamed after the league. The field’s original grandstand was torn down and replaced by a 500-seat bleacher. In 1920, the field’s final year of use, additional seating took capacity to about 1,000 onlookers.

With the opening of Battersby Field, maintenance money was diverted, and Elks Park fell into disrepair. The stands were torn down and the field saw recreational and school play before disappearing around 1929.

Elks Field stood on the present-day location of Bellingham High School, with the edges of the stadium property along Kentucky Street and what is now the high school’s football field and tennis courts.

Waldo Field (1924–1930s)

Located on land that is now WWU’s Miller Hall and Red Square, Waldo Field was named after the school’s fourth president, Dr. Dwight B. Waldo, who served from 1922–23.

The field was dedicated on November 16, 1923, and began its life hosting football games. A baseball diamond was added next to the football field in 1924, and the university’s first track was also installed at Waldo, in 1925.

Both the football and baseball teams eventually defected to Battersby Field, and Miller Hall’s 1943 construction likely led to Waldo Field’s demise. The Hall was expanded in 1968, with Red Square — the approximate location of the baseball diamond — built in 1969.

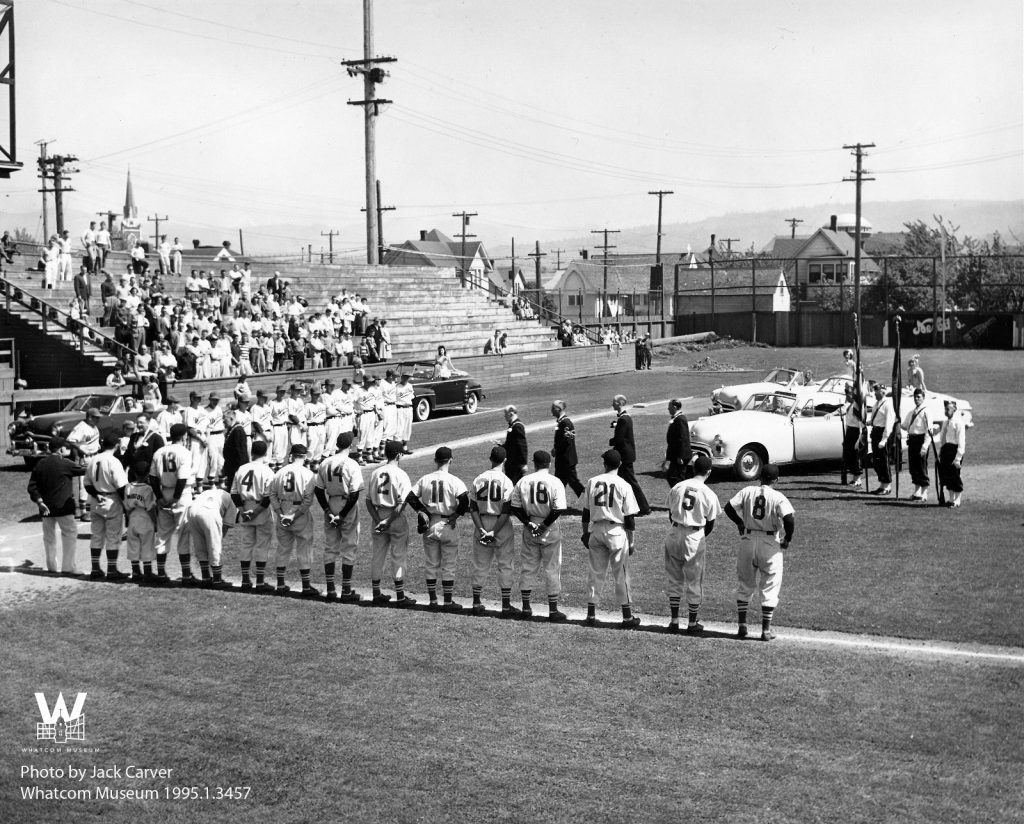

Battersby Field (1921–1962)

The lot that became Bellingham’s longtime home for baseball began as land leased to a church for a playground in 1910. Used as a crude site for some football and baseball games, the Bellingham School District bought the field in 1913 to hold physical education classes.

In 1917, the field’s northwest corner at the intersection of F and Girard Streets saw the Whatcom High School baseball team move in, playing in front of a new grandstand. Originally called Whatcom Athletic Field, it was renamed Battersby Field in 1918 to honor Robert Battersby, a longtime school board member.

Upgrades in 1921 made Battersby host to the city’s Twilight League games, and about 1,400 people showed up to see the first game between the Elks and the Bloedel-Donovan team.

Battersby added lights in 1935 for night baseball, becoming the only lit field north of Seattle. Over the decades, the ballpark held all manner of games: grade school and high school matches, semi-professional Northwest League games, and various city and county leagues.

Bellingham teams that played at Battersby included the Elks, Tulips, and Chinooks — a class B minor league franchise. In 1940, a new NW League team called the “Mount Bakers” was formed, but a local sportswriter encouraged player-coach Andy Padovan to change the name. Soon, the Bellingham Bells were born.

Barnstorming exhibitions also yielded some extraordinary visitors. In 1932, Mildred “Babe” Didrikson — a two-time track and field Olympic gold medalist and future co-founder of professional women’s golf — pitched the opening two innings against the Bellingham Tulips for the House of David team.

Semi-pro Negro League teams like Cuba’s Colored House of David and Gilkerson’s Union Giants played at Battersby in 1929 and 1931, respectively. On July 28, 1940, the Kansas City Monarchs came to town. Despite expert opening innings by legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, the Monarchs blew a 9–1 lead and the Bells won 10–9.

Besides baseball, Battersby Field also hosted football games, track and field events, boxing matches, and even pageants.

Two things led to Battersby’s 1962 demise. The first was the pending construction of Civic Field, which provided separate spaces for baseball and football. The second was the infamous Columbus Day storm of 1962, which destroyed the roof and light poles of the field’s main grandstand with nearly 100 mph winds.

Basic emergency repairs were estimated at $3,800 ($36,000 today), and it was decided to instead demolish the grandstand and focus on finishing Civic Field facilities. A grandstand-less Battersby, with a small replacement backstop, continued to see baseball through the years.

Today, Battersby continues to see community use as a place for middle school sports, adult recreation leagues, and daily joggers and walkers.

Much of the information in this article is sourced from “Bays to Bells,” a local baseball history book by Wes Gannaway and Kent Holsather. If you’re interested in local history or baseball, it’s a real gem of a book.