Today, Bellingham’s Silver Beach neighborhood is a collection of expensive homes and popular recreation sites on Lake Whatcom’s shoreline. But over a century ago, it was the site of a sprawling amusement park known as the ‘White City,’ complete with a roller coaster, Ferris wheel, resort hotel—and even a pit with live bears.

The park entertained the masses for more than a decade, before vanishing into history for reasons that remain unclear. This is the story of Bellingham’s ‘White City.’

Glimpsing the Future

In the 1890s, Silver Beach was an unincorporated community outside Bellingham’s city limits. It was home to the modest dwellings of working-class people, many of whom were employed at nearby shingle mills. But Reginald Jones and E.F.G. Carlyon, two entrepreneurs, saw a different future. They envisioned the area—particularly a patch of land next to Lake Whatcom—as a bustling resort community with modern street car access.

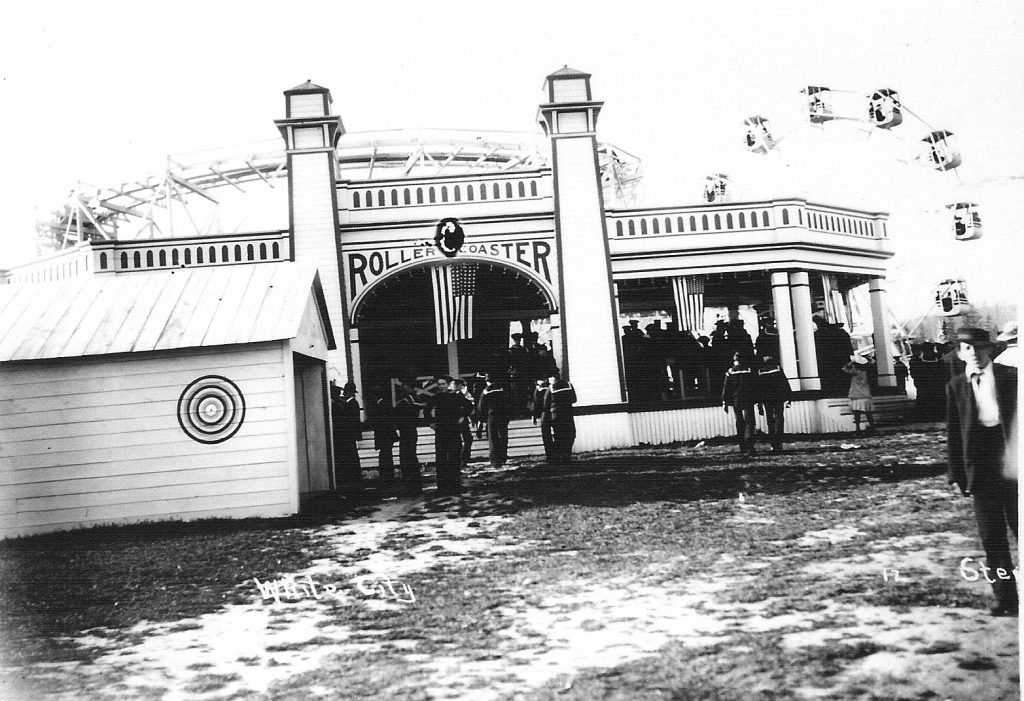

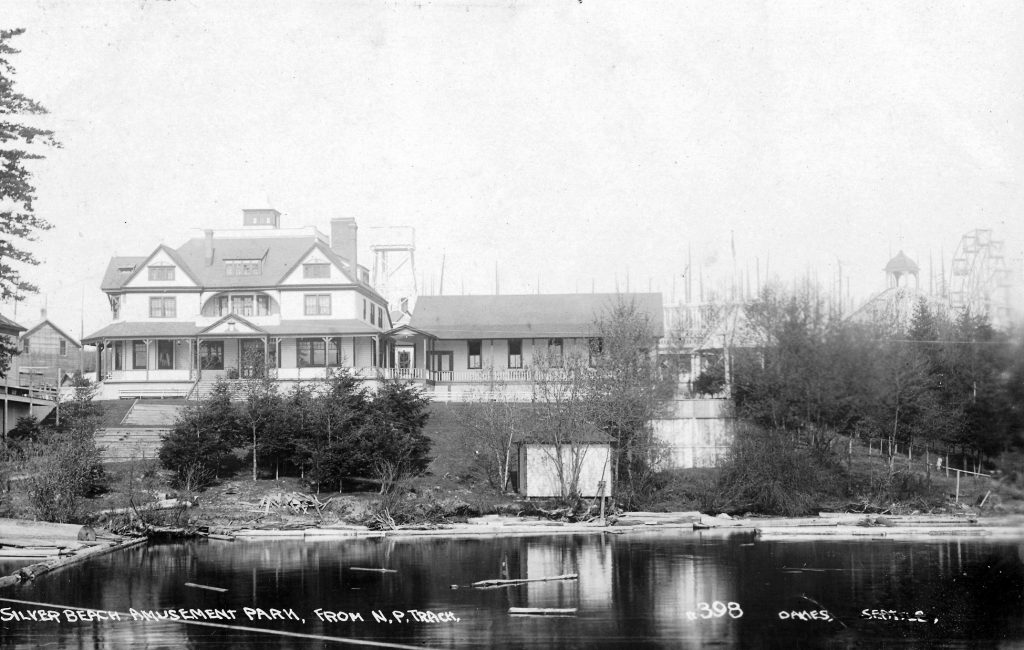

The two men opened the Silver Beach Hotel in May 1891, but promised street car access was delayed until 1892, forcing visitors to initially rely on wagon service to get there. After a national economic depression was triggered in 1893, the Silver Beach Hotel struggled.

Jeff Jewell, archivist at Whatcom Museum, says the place became a roadhouse and bar that brought in seedy clientele, many of whom rowed there in boats to drink. Jones and Carlyon, the hotel’s initial operators, eventually wound up suing each other and declaring bankruptcy.

But 1893 brought another event that would shape Silver Beach: the World’s Columbian Exposition. Held in Chicago, it was the U.S.’s first World’s Fair, serving as a literal beacon of wonder, lit at night by thousands of incandescent lights that gave the fairgrounds a beautiful glow and the nickname “The White City.” It was also site of the first Ferris wheel.

Silver Beach Amusement Company

By 1906, “White City” had become a generic term for an amusement park. There were thousands of them across the country, offering cheap entertainment long before TV or radio.

That May, Pittsburgh capitalist C.H. Chandler visited Lake Whatcom as the guest of William Gwynn, a Bellingham realtor. The men fished, and Chandler was impressed enough by the area to move here. By then, the Silver Beach Hotel had been joined by a second-rate amusement area. According to the book Looking Back: Memories of Whatcom County, there were flying swings and “Shoot-The-Chutes,” but little more to entertain anyone.

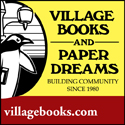

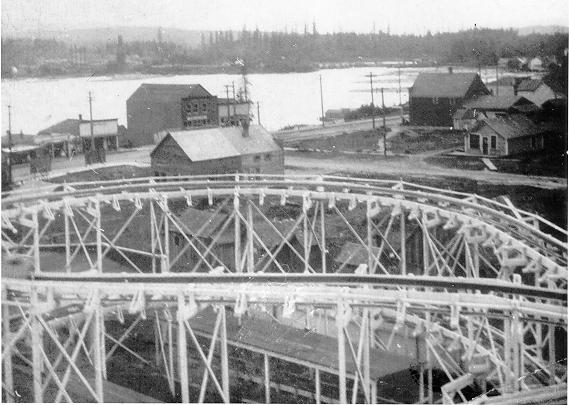

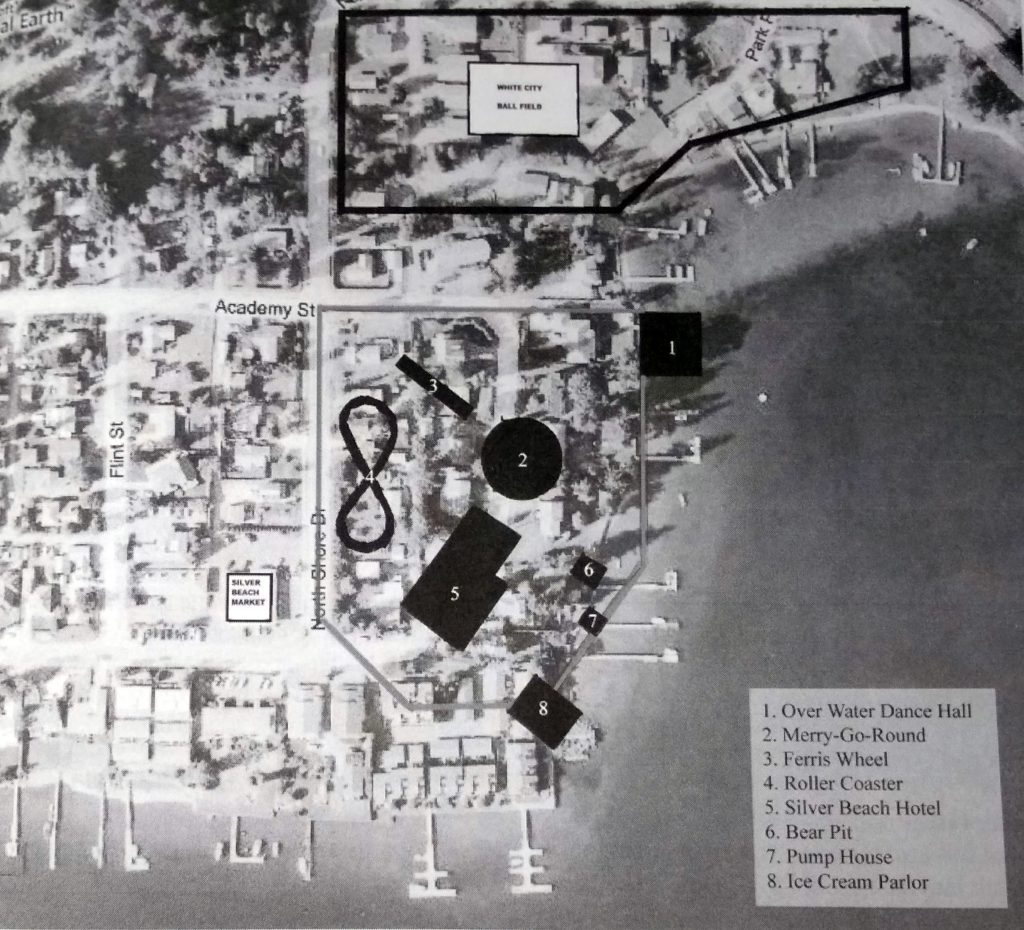

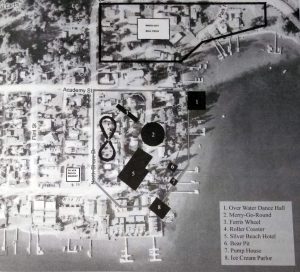

Chandler had a grand vision for developing the area into a recreational paradise. He and Gwynn formed the Silver Beach Amusement Company and drew up plans; Chandler invested tens of thousands of dollars to purchase property and the hotel. Construction began that summer, and included the building of a figure-eight roller coaster and 75-foot-tall Ferris wheel. A large merry-go-round was also installed.

On the weekend of September 6, 1906, when patrons were first allowed on the rides, more than 3,000 people reportedly rode the roller coaster. The White City was open briefly that season, closing for the winter in October. Gwynn became operations manager while Chandler wintered down in Florida, with plans to expand the park.

According to the book Bellingham Then & Now, those plans included adding a house of mirrors, tunnel of love, dance pavilion, toboggan slide, baseball diamond, tennis courts, and a bear pit.

Chandler also wanted a variety of performances held, including the “flying flaming dive.” According to Looking Back, this consisted of a woman scaling a tall tower clad in an asbestos suit, covering herself in gasoline, and then setting herself on fire. She’d then dive into a tank of water below, amazing the crowd by emerging uninjured.

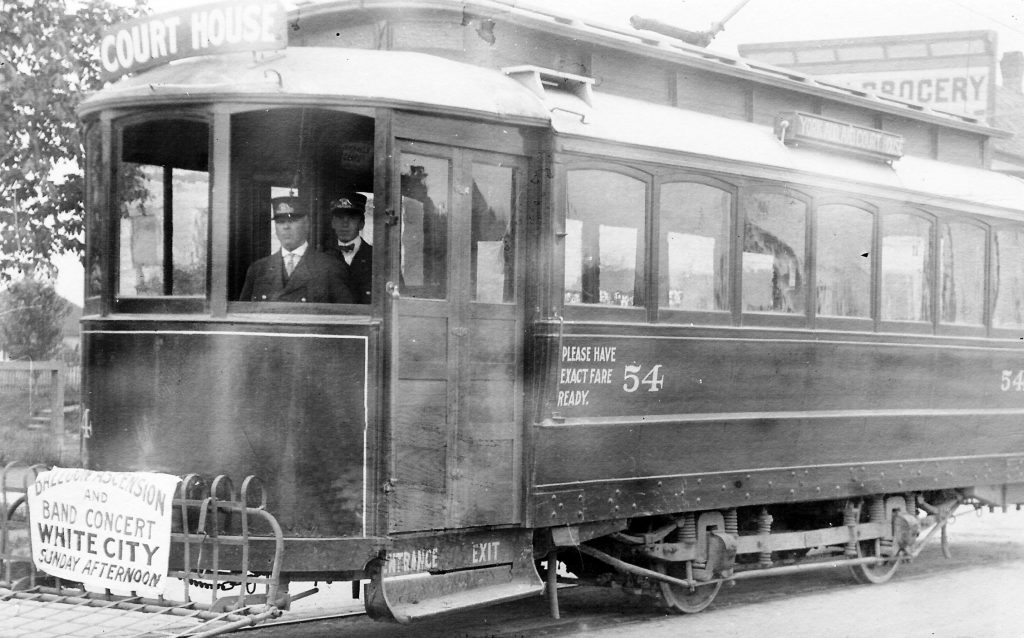

In the end, many of these grandiose ideas never materialized. But when the White City officially opened on Memorial Day in May 1907, 10,000 people were there to see it. Jewell says the park’s success was owed to the symbiotic relationship between the amusement company and the rail company, Whatcom County Railway & Light.

“The amusement park got its customers because there was a street car line, and the street car line got its weekend customers because there was somewhere to go at the end of the line,” he says. Putting leisure destinations at trolley line terminuses, he adds, was incredibly common during this era.

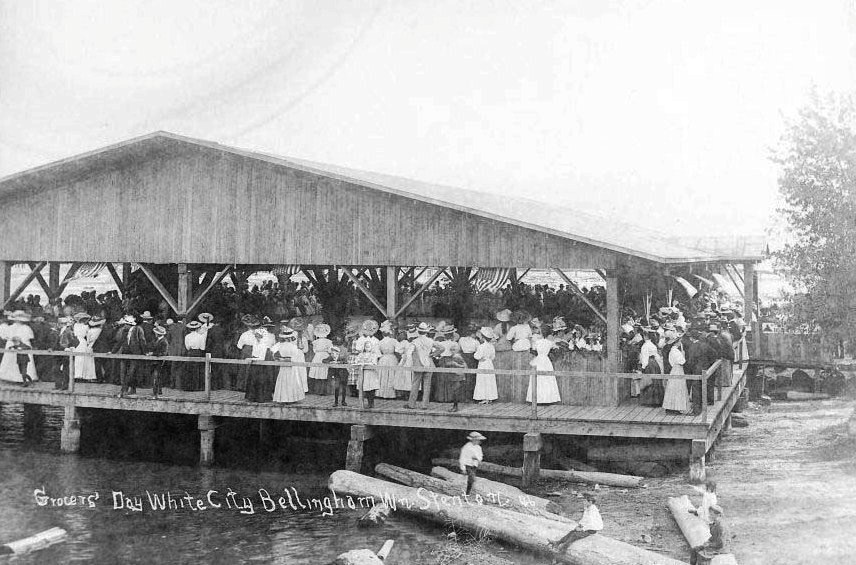

The White City continued, open on weekends from May to October. It added a dance pavilion built on pilings to extend over the lake, and a boat house with rental boats became incredibly popular.

In 1908, White City played host to special events. There was “Airship Week,” featuring daring dirigible demonstrations, as well as “Fleet Week,” which provided free food and rides to thousands of visiting U.S. Navy sailors whose ships were parked in Bellingham Bay. The White City was also frequently rented out for company picnics, annual ethnic events like German picnics, and religious retreats.

Decline and Demise

But the White City also endured setbacks.

Two black bear cubs placed into a pit were cute novelties until they became difficult adults; eventually, they were shot. During one event in which a trained dog parachuted from a hot air balloon, the dog drowned in the lake before it could be rescued, traumatizing many of the children watching.

Things got worse in 1910. Chandler, who’d become manager in 1909, died of a stroke. Bellingham also declared a prohibition on public alcohol consumption, affecting the park’s ability to draw adult customers.

New ownership and seasonal agreements led into the 1910s, but White City attendance and revenue kept dropping. The death knell for the park is unclear. Hal Reeves, an old Bellingham radio host, insists a fire burned the place down in 1915. Jewell says that interviews he’s conducted indicate it likely closed due to the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which temporarily closed many public places – including theatres – at its height.

Regardless, the property was sold to a fuel company and dissembled in the 1920s. The hotel became miner’s quarters for a nearby coal mine that also wasn’t successful; wood from the roller coaster was supposedly used as mine shaft supports.

By the 1930s, street car lines were a thing of the past in Bellingham, replaced by trackless streets for automobiles. Although Bellingham had the occasional Ferris wheel, it never had another White City. Today, across the street from Silver Beach Grocery on Northshore Drive, there’s no indication of where a roller coaster used to stand. Poplar Drive, lined with residential homes, gives no insight into the past.

But for a time, this area was a joyful amusement to local citizens, temporarily freeing them from the hardships of their long-ago lives.

“It’s a miracle that it even ever existed at all,” Jewell says, reflecting on the White City. “We don’t live in a climate that allows for an amusement park.”

Photos courtesy of Bellingham Then and Now authors Kent Holsather

and Wes Gannaway