The COVID pandemic has affected us all. Many have been forced into isolation just as they were hoping to make new friends. Others lost close friends or relatives to the virus or became sick themselves. All of us have stories to tell about what the pandemic has taught us, cost us, or meant for us. The Whatcom County Health Department gets an up-close view of these stories every day.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the first experienced in the U.S. The 1918 influenza epidemic sickened one-third of the planet’s population and took more lives than almost any other natural disaster. But that epidemic didn’t start and end in 1918—multiple waves continued until 1920.

One can imagine how different things might have been if vaccines were available in 1918.

The echoes from the 1918 pandemic continue to ring today for some, like Bellingham resident Pauline Sterin. She’s been thinking a lot about how that earlier pandemic touched her life—or, rather, prevented others from touching hers.

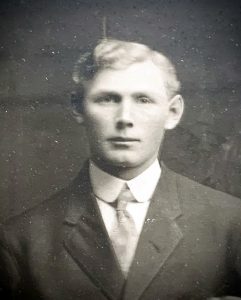

Sterin’s father was less than a year old when both of his parents died in the 1918 flu, leaving him and his brother orphans.

“If [my grandparents] had a vaccine, I might have had a chance to know them. But they didn’t, and now they’re largely forgotten,” Sterin said. “It pains me to think of the people dying now because they haven’t been vaccinated, whose children and grandchildren won’t have a chance to know them.”

The CDC estimates that 675,000 people perished during the 1918 flu pandemic in the United States. It was the deadliest pandemic in recent history, but the COVID-19 pandemic is catching up. As of August 4, 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has claimed 611,791 lives in the U.S. alone, according to the CDC.

To date there have been more than 35 million COVID-19 infections documented in the U.S. by the CDC. Many people infected by COVID-19 show no symptoms, but for some people the virus can be deadly, especially if their immune systems are compromised. That’s why long-time local Bruce Kraig took the threat of COVID-19 infection very seriously.

“I was born with a lot of what I call genetic challenges, and one of them is a defective immune system,” Kraig said. “I majored in early childhood education and working with the little kids for 20 years, was sick almost constantly.”

Kraig said he has lived most of his life practicing the kind of safety techniques that other people had to adopt during the pandemic because his genetics required him to. But even so, Kraig could not avoid the virus.

Kraig was exposed to COVID-19 in his home, which he shared with several other people. One of his housemates attended a Christmas Eve dinner party with a friend who was positive for COVID-19, but didn’t have any symptoms. Kraig’s housemate became infected, along with everyone else at the party, and brought the virus back home to Kraig.

Kraig’s first symptoms hit on the December 29. The earliest symptoms, Kraig said, were easily managed with ibuprofen and zinc lozenges, but he was feeling much worse by New Year’s Eve. He called a clinic, scheduled an appointment to get tested, and found out on January 2 that he was, indeed, positive for COVID-19.

Because he shared a home with others, Kraig was instructed to isolate at the county’s isolation and quarantine facility on Samish Way.

“I told my friends I felt like I was under siege, and it was very disconcerting because this was unlike anything I’d ever had,” Kraig said.

Kraig was able to move back home about a week later after his symptoms abated. Kraig said he was still very worried, though, because of what he’d heard could happen in the first couple of months after recovery as a result of internal injuries sustained during infection.

“I had been reading about all the things that could happen two you within eight weeks of getting over COVID,” Kraig said, “so I was very anxious for all of January and February.”

Fortunately, in early April, Kraig’s healthcare provider told him he was eligible to be vaccinated. Kraig jumped at the opportunity, even though he’d already survived infection once. He said some of the symptoms felt familiar, as though his immune system was saying “we recognize what this is, and we don’t like it.” But within an hour and after taking an Ibuprofen, Kraig said, all his symptoms were gone, and he experienced no side effects after his second shot.

Even with the vaccine, Kraig remains cautious as he makes his way back out into the world. He’s seen two movies at the Mount Baker Theatre and a movie at the Pickford.

“Yesterday, I went to the concert for the Bellingham Festival of Music at Western, my first in-person orchestra concert in exactly 500 days,” he says. “The difference between enjoying that online and in person—it’s 100 times better to be there in person. It just makes all the difference in the world.”

Kraig isn’t the only Whatcom County local whose immune system complications made them hesitant to venture out during this pandemic. Tiahna Skye, a local mental health coach, has had radiation treatments on her lungs and heart, which puts her at high risk of serious complications. But her status as a recent arrival also meant she yearned for community.

Skye relocated to Whatcom County just before the pandemic took hold. Her concern over the virus forced a shift from looking forward to meeting new people to being concerned about interacting with others.

“I anticipated meeting new people and making new friends and discovering the community and how I might like to contribute to it,” she says. “What I did not anticipate is that I would find myself socially isolated.”

Skye dove into her work, spent lots of time in nature and immersed herself in creative projects. Although she said she loves her work and her own company, she was thrilled when the vaccine arrived, even though she would not describe herself as a “vaccine-getter.” Skye said the process felt easy, safe, and even comforting.

“I had zero reaction to my first shot, not even a sore arm,” Skye said. “I did have a couple of rough days after the second shot, but I have since felt so much safer shopping for groceries, going to the dentist, and getting my hair cut.”

Because the pandemic is not over, Skye said she will continue to wear a mask in public, for a couple of reasons.

“One, I want others to feel and be safe around me,” she said. “Two, I feel strongly that we all need to care about and for each other.” She said that getting vaccinated and wearing a mask are two of the surest paths out of this pandemic.