Previous WhatcomTalk articles have chronicled several of our area’s ghost towns, but it’s difficult to fit them all into just one article. Throughout Whatcom County’s roughly 2,500-square miles, there’s no shortage of tiny hamlets long erased from existence.

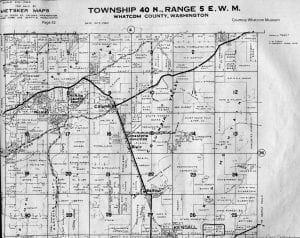

In the Columbia Valley, just north of Kendall, there’s evidence of another long-forgotten settlement: It was known as Balfour.

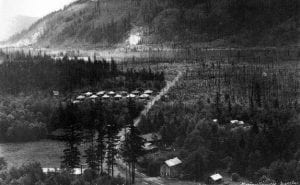

Once home to a bustling company town for limestone quarry workers, the location thrived for about 15 years before the quarry was shut down, leaving just a few residents living in area homes. Today, there’s not a great deal of information or photos to suggest Balfour ever existed at all, but for those who worked and lived here a century ago, it was the center of their universe.

The Hills Are Alive With Money

Around 1900, the Balfour-Guthrie Investment Group—owned by a larger company from England—had their eyes on choice land at the bases of Sumas Mountain and Red Mountain, both in north-central Whatcom County. These areas contained vast quantities of limestone the company wanted to extract with large, kilned quarry operations.

Their primary obstacle was a legal one: foreign investment groups couldn’t own mining claims in the United States at the time. But after a legal challenge reached the Supreme Court and resulted in a change in precedent, Balfour-Guthrie established another business entity, called the Olympic Portland Cement Company, and got to work.

By 1905, the company had plans for a town named Balfour with up to 700 homes, many of which would house workers of their new quarry. By 1914, however, only 12 homes were constructed. The company supplemented these homes with three bunk houses, a cook house and several other structures.

The new quarry employed more than 100 men, and a small station along the nearby Bellingham Bay-British Columbia Railroad was built to load crushed limestone into and out of train cars. A spur line was eventually built, bringing the railroad directly to the quarry. Loaded rock was then shipped to another facility at Whatcom Harbor, on what’s now the Bellingham waterfront.

With workers’ families moving into Balfour, a school soon opened on the second floor of the cook house. The school’s first teacher was the wife of a quarry worker, while her eventual replacement was a woman who lived in Bellingham and left for Balfour each day at 6:00 a.m. on a three-hour train ride.

Eventually the school was shuttered, and children in Balfour had to walk two miles to the nearby Kendall school. Walking to Kendall wasn’t uncommon for Balfour residents, as they often followed the railroad tracks there, on foot, to buy groceries, check mail, or hop a train to Sumas. At its peak, during World War I, Balfour had a population of about 200.

Rural mail delivery reached Balfour in 1922, and groceries and supplies were delivered to the settlement by horse and buggy. At some point following WWI, Balfour also sported a dance hall that allegedly played host to local orchestra musicians deemed to be among the county’s best. Olympic Portland Cement Co. also sponsored a local baseball team in the 1920s.

At some point, another limestone quarry was opened at the base of Red Mountain, just a few miles away. Regardless of what quarry the men were employed at, working conditions were dangerous and pay was not ideal. Many were probably exposed to cancerous elements, like asbestos.

Decline and Decay

By 1928, the Balfour quarry wasn’t yielding enough limestone to meet its owners’ expectations, so it was closed. Operations were moved a few miles up the road to the growing Red Mountain quarry. With improved roads and cars more prevalent, workers no longer had to live at on-site company buildings, and Balfour’s residents dwindled. By the 1940s, only three of the 12 homes were still standing. Balfour’s longest residents—the family of former quarry timekeeper D.E. Stewart—lived at Balfour for 35 years. Eventually, they also left.

Sometime in the 1950s, the last residents of Balfour—the William Golden family—moved, leaving the site officially vacant. In 1964, Balfour’s final two homes were demolished, and several fires in the following years claimed other forlorn buildings.

Railroad tracks leading to the quarry were eventually paved over, and in ensuing decades, nearby residential developments like Peaceful Valley and Paradise Lakes sprang up nearby. A country club and golf course were also constructed not far from the former settlement. The golf course closed in 2006.

Today, almost nothing remains of Balfour, and the site itself remains mostly undeveloped as of November 2020. Whatcom County Water District 13 operates a drain field were Balfour’s homes used to stand. Several gravel roads crisscross the area, and fruit trees planted by long-ago residents can still be seen growing.

Down an unpaved road leading to the base of Sumas Mountain, you can glimpse a giant concrete ruin—all that’s left of the once-thriving quarry—being reclaimed by nature. The ground around the 30- to 40-foot-high structure contains visages of the past: rusted bolts poke up through fallen leaves, twisted pieces of metal lay strewn haphazardly, and crumbling concrete is covered with moss and fungi.

Walking through it is to come face-to-face, somewhat eerily, with a history that’s nearly as ghostly as the people who lived it.

This land, now occupied by a water district drain field, once contained 12 homes built by the Olympic Portland Cement Company about 110 years ago. Photo credit: Matt Benoit

Twisted pieces of metal are scattered about in the area near the concrete ruins of what used to be a limestone quarry. Photo credit: Matt Benoit

Photo credit: Matt Benoit