Ghost towns have long bewitched thrill-seekers. Monuments to timeless yet transitory industries of mining, logging, and fishing, Washington’s own ghost towns communicate history beyond words—and Whatcom County is no stranger to these ephemeral areas.

Bellingham was once four towns: Bellingham, Sehome, Fairhaven, and Whatcom. Census-designated places such as Marietta-Alderwood, Glacier, and Maple Falls once thrived with bygone industry. But Whatcom County’s true ghost towns and their histories, although faded and overwritten, are etched into mountainous, forested, and coastal landscapes.

Ghosts of Gold: Chancellor, Barron, and Shuksan

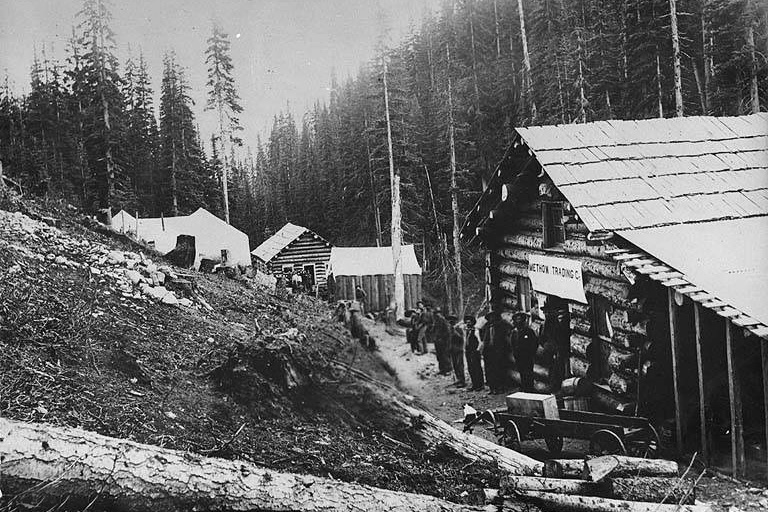

Although the Mount Baker Gold Rush began with the 1897 discovery of Lone Jack Mine, the North Cascades had mining camps since the 1870s; many developed general stores, post offices, hotels, sawmills, blacksmiths, and saloons. Yet Whatcom County’s mining towns disappeared as quickly as they boomed, owing to harsh conditions and diminishing returns.

Near Hart’s Pass, mining camp Chancellor became a boom town by 1895 (peak population 3,000). The Chancellor Gold Mining Company ran a power plant from 1905 to 1907, briefly hoping for railroad connections. The plant ran DC electricity through a Pelton wheel via water, which lit up the camp.

Further east toward Hart’s Pass, the town of Barron boomed (peak population 2,500) after Alex Barron discovered gold in 1892. Colonel W. Thomas Hart purchased his claims for a sum between $50,000 and $80,000, building a wagon road for mine access. The boom lasted two years until many miners left for Alaska in 1899. Allegedly, those remaining abandoned the camp so suddenly in 1907 that they left buildings, machinery, wagons, and goods frozen in time.

Formerly named Gold Hill, mining supply base Shuksan was an early endpoint of Mount Baker Highway. After the Lone Jack Mine’s 1897 discovery, Shuksan grew to 1,500 residents mainly living in tents. It became a ghost within eight years. The Lone Jack Mine’s ownership frequently changed hands, producing until 1924, as the Mount Baker Gold Rush declined.

Today, Chancellor’s hotels and power plant lie in ruin on remote Chancellor Trail. Barron’s cabins, hotels, and machinery remain—some dilapidated, others remarkably intact—behind a gate on road NF-700, are off-limits without permission. Shuksan also lies on private property near Shuksan Picnic Area, reportedly vacant.

Railroaders’ Lament: Goshen and Park

Scrapped railroads often took farming and logging communities with them, as in Goshen west of Deming and the Nooksack River. Settled in 1885, Goshen had a post office from 1891 to 1918 and a population of 100 in 1915. Goshen competed for Northern Pacific Railway access against Whatcom, Seattle, and winner Tacoma, and transported logs through Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railroad from 1916 to 1942.

Goshen Nooksack Cemetery (alternatively Sulkanon or Salkanom Cemetery for donor Robert Sulkanon) is the town’s oldest vestige among modern houses. The name survives in Goshen Road, Everson-Goshen Road, and Goshen Community Church. Goshen’s memory survives in famous Pacific Northwest writers’ fictional references: Ella Higginson in The Forest Orchid and Annie Dillard in The Living.

Park was a logging town southeast of Lake Whatcom, named for settler Charles Park who rowed from Geneva. It was the southern older sister of Blue Canyon in the early 1880s. Blue Canyon Mine operated from 1891 to 1919, hauling coal via Bellingham Bay and Eastern Railway and growing the population to 1,000. 23 men died in the 1895 mine explosion, one of Washington’s worst industrial accidents. Park’s post office operated from 1884 to 1925, Blue Canyon’s from 1892 to 1905; both declining as coal became obsolete and logging activity moved.

Today, visitors to Park can see the restored general store, railroad, and Great Northern boxcars behind a fence. Blue Canyon is an unincorporated community.

Ancient Mariners: Semiahmoo

Some ghost towns hide in plain sight among the living, as in Semiahmoo: a 125-acre spit near Blaine. Prospectors pursuing the Fraser River Gold Rush in 1858 established a boat launch and trading post on the spit. In 1884, settlers platted the entire Drayton Harbor region as “Semiahmoo” after a Salish band. After Blaine’s 1890 renaming, two industries distinguished the towns—Blaine boomed through logging, Semiahmoo through fishing.

Semiahmoo built Whatcom County’s earliest salmon cannery—eventually the world’s largest—in 1881. It packed 36,244 sockeye cases on becoming Alaska Packers’ Association (APA) in 1893. APA operated the cannery for 75 years, packing 100,000 cases per season in the mid-1950s. The Plover pedestrian ferry began transporting cannery workers between Semiahmoo and Blaine Harbor in 1944. On APA’s 1982 dissolution, Trillium Corporation purchased the land for Semiahmoo Resort.

Ghost buildings still stand beside Semiahmoo’s resort and restored haunts. APA’s bunkhouse and office is now the Cannery Lodge event venue. Drayton Harbor Maritime operates the Plover ferry and APA Museum in the former cannery, touring visitors through maritime history. The ferry boards by the former net warehouse—derelict like the nearby fishing boat, docks, and water tower.

Semiahmoo Spit presents spectacular views of the Cascades across lowlands—each ghost town watching over another. As long as prospective visitors pay respects, ghost towns will never really die.