The realities of life during the COVID-19 pandemic, from social distancing and quarantines to shuttered schools and businesses, are things we’ve never encountered before.

Sometimes a historical perspective is useful. Just over a century ago, the 1918-19 “Spanish Flu” pandemic killed hundreds of thousands of Americans—and tens of millions worldwide—in only about 12 months.

Bellingham and Whatcom County residents weren’t spared from the devastation of the terrifying flu strain, which primarily killed healthy people between ages 20 and 40, often through the secondary development of pneumonia.

A Germ At Work

Nobody knows how or where the new flu strain originated, but closely quartered, but far-traveling soldiers undoubtedly spread it.

In 1918, the world’s attention was on World War I, and military camps across the U.S. were training thousands of young men for battle. That March, hundreds of men at Fort Riley, Kansas, became the first reported cases of the new flu. The illness also popped up in New York and elsewhere, but didn’t appear much worse than a normal flu outbreak. Most people recovered, and cases fell off through the summer.

In Europe, however, the virus spread intensely among soldiers. Its nickname of “Spanish flu” likely developed because Spain—a neutral country during WWI—had no morale-based news censorship. The flu’s spread was heavily reported there, leading some to assume it began there. Even more so, U.S. newspapers and citizens circulated propaganda-like rumors that a German submarine, towed into a Spanish port, likely launched the disease’s spread.

In early September, a second wave of flu infections began in Boston and spread quickly. These cases would be much deadlier, occurring at a time when medicine lacked the annual flu vaccines, antibiotics, antivirals, and mechanical ventilators of today.

In Bellingham, front page headlines were still dominated by WWI and the exploits of local men fighting the Kaiser. But in army camps across the country, the flu was exploding. By September 24, the U.S. surgeon general announced Spanish flu present in 26 states, and some East Coast states had begun debating school, church and other public closings. More than 100 cases were reported at Tacoma’s Camp Lewis.

On September 27, the Bellingham Herald featured a short article in which Dr. L.R. Markley, chairman of the city board of health, announced Bellingham’s first two flu cases. Markley noted the illness could easily cause pneumonia and, unless contained, could become “an alarming epidemic.” By this time in many places, it already was: 30,000 cases at army camps across the U.S., with cities like Boston and Baltimore seeing daily deaths in the hundreds.

On October 5—the same day Whatcom County’s annual fair was to begin—Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson announced the closure of every indoor public gathering place citywide. By then, nearby naval training centers were reporting hundreds of flu cases and several deaths. Hanson noted the uncertainty of actual citywide case numbers, as many people were being misdiagnosed with common colds.

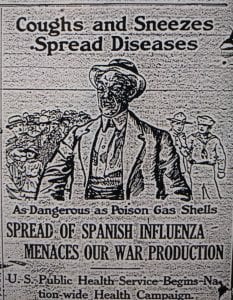

On October 8, Bellingham Mayor John A. Sells issued a closing order for all public gathering spots, including schools, theaters, pools, card rooms, dance halls, and churches. In the Herald, city health officer Dr. W.W. Ballaine warned residents to avoid crowds and use handkerchiefs to mask coughs and sneezes. Chief of Police Max Lasse said he would “rigidly” enforce an ordinance banning spitting on sidewalks, a common but unsanitary habit of the era.

The order closed city schools until October 21, postponed the dedication of the new Liberty Hall, and closed the YWCA to the public, save for its cafeteria. Funerals were ordered to be small and private. Outdoor gatherings were still allowed in Bellingham, but not in Seattle, having been banned on October 9 after 313 new flu cases were reported. In one 24-hour period, the Herald noted that more than 11,000 new cases were reported in army camps nationwide. Soldiers from Camp Lewis were banned from visiting Seattle, and soldiers with flu symptoms were quarantined.

Fears and Cures

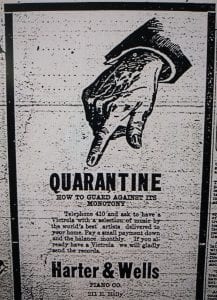

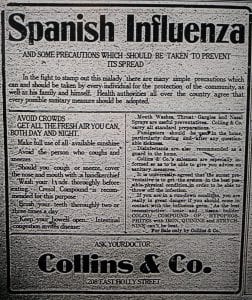

Just as we’re subject to misinformation regarding our current pandemic, so too were the people of 1918 during theirs. Throughout the Herald, local doctors and drugstores often ran ads indistinguishable from news articles. Some offered trustworthy advice, while others peddled curing elixirs like “Oil of Hyomel.”

While vaccine work continued in labs nationwide, false and often idiotic cures made headlines: a homeopathic doctor in Pittsburgh claimed to have quickly cured patients with a hypodermic injection of iodine and creosote. At one point, a Bellingham resident wrote the city council a letter proclaiming the flu could be warded off with yard fires that burned a combination of “rosemary oil, rosin, pitch, tar and Sulphur.”

Herald articles show public officials changed their rhetoric during different points in the pandemic, downplaying the flu’s severity one week and pleading people take it seriously the next. By mid-October, Bellingham was reporting dozens of new cases daily. On October 13, the first death occurred: Anne Ruth Harrison, an 18-year-old student at the Washington State Normal School (now Western Washington University), died from pneumonia after a week of illness.

Two days later, 25-year-old Walter Shanley, also sick one week, died at his parents’ home while visiting them on Army leave. His 23-year-old sister would die from the flu 10 days later, leaving their parents childless. By this time, rural county towns like Everson and Lynden were also reporting cases and closing schools, and flu deaths in U.S. Army camps topped 10,000.

Many organizations did what they could to help. The Bellingham Chamber of Commerce distributed signs with messages like, “Help to win the war by preventing the spread of the disease,” and local Red Cross chapters recruited nurses and volunteers to care for the sick and produce extra gowns and masks.

As the pandemic progressed, many cities ordered citizens to wear gauze masks in public. Sometimes, these orders had very negative results. In San Francisco on October 28, a deputy health officer shot a man in public for refusing to don a mask. After being taken to a hospital for treatment, the man was arrested. In Seattle, people lacking masks were kept out of stores and public places by guards, and often refused fare by street car conductors.

By the end of October, Bellingham had 22 flu deaths. On November 5, with statewide cases coming in by the thousands, the state board of health ordered masks—no less than six gauze layers thick—be worn by anyone in public. Amid the Herald’s thorough description of when masks be worn, it noted wearing one while eating wasn’t required. In addition, stores and street cars kept windows open for ventilation (regardless of the weather), and ice cream parlors and soda fountains sanitized glasses after each use by boiling them.

Two days later, Police Chief Lasse ordered the arrest of anyone seen in public without a mask. That day, Bellingham police slapped cuffs on 22 people. Understandably, businessman and citizens protested, and the next morning, the mayor told police to stop enforcing the order. All cases were dismissed, but not before the detained spent hours in jail. Some, the Herald said, intended to sue the city over the matter.

In an official statement, Mayor Sells called the masks a “farce,” noting several physicians had told him they were actually unnecessary and even unsanitary.

“If the health department wants me to enter stores and arrest persons for failure to wear masks,” he said, “they will have to furnish me with warrants.”

A False Lull

By mid-November, cases dwindled to a few dozen a day, and deaths dropped to almost zero. On November 11, Mayor Sells dropped the public closure ban in Bellingham, slightly ahead of the statewide repeal. In the following days, theaters re-opened, as did both the city and Normal schools after six weeks off. Only students who were well were allowed back, though, and recently sick pupils required a physician’s certificate proving they weren’t contagious.

Despite this return to “normal” life, by the beginning of December it became clear things weren’t so normal.

Bellingham recorded 29 flu deaths in November, and a Thanksgiving dance in Marietta helped further spread the illness. On December 3, the city health board met to discuss another ban on public places, with new cases in the hundreds. The next day, they announced any family with a flu-infected member would be quarantined. No family member could leave their home except for the primary breadwinner, even if they weren’t sick. Schools and public places, though, remained open.

On December 6, former Bellingham resident and Los Angeles actress Olive Adair made the front page of the Herald after being mistakenly pronounced dead at an L.A. hospital. After four days of suffering with the flu, doctors wheeled her into a “dead room,” where a priest discovered she was still alive.

By December 16, there were more than 200 new daily flu cases, with a handful of deaths. The next day, the city health board unanimously voted to again ban public gatherings. Although things remained civil, business owners voiced displeasure; several theater owners said they wouldn’t close unless it was proven the health board could legally enforce the order. Schools, the city superintendent said, wouldn’t close unless all other places children could go also closed. Even Dr. Ballaine lamented the economic toll of another closing order.

On December 19, with hundreds of new cases and family quarantines deemed a failure, a compromise was reached: theaters, churches and schools would remain open. Dance halls and skating rinks would be closed, and other public businesses would use guards to prevent the sick from entering.

“Anyone coughing in public places,” the Herald noted, “will be requested to leave.”

Despite the order, all city schools had closed again on December 17, and stayed that way. Normal students were given homeschool assignments through the Christmas break, and graduation ceremonies were postponed. Most churches also remained closed, though six Lutheran churches stayed open.

On December 21, Dr. Ballaine’s weekly report showed 15 deaths, the highest weekly Bellingham toll since the epidemic began. About 80 percent of the city’ flu deaths, he noted, were between ages 17 and 30. The city health board was still on edge, and said they’d close everything but grocery and butcher shops if things didn’t improve.

On Christmas Eve, a new city council ordinance was introduced. It gave the city health board free authority over epidemic situations; those disobeying their orders would be charged with misdemeanors, fined at least $100, and jailed up to a month. The next week, however, the ordinance was unanimously voted down.

On December 30, city schools reopened, and the Normal School soon followed. Attendance was initially about half, but improved quickly. By January 4, 1919, Dr. Ballaine reported just 166 new flu cases, with four deaths. A few cases continued off-and-on through March, when the Spanish flu peaked a final time across the U.S. before disappearing forever.

The Future

There’s no exact number of Bellingham or Whatcom County Spanish flu deaths, but in Bellingham alone an estimated 100 people died within six months, mostly between October and January. Thousands more became sick. In Seattle, over 1,500 died, with more than 6,500 dead statewide.

The final U.S. death toll from the 1918-19 pandemic is estimated at 675,000 people—more than all U.S. war casualties from WWI, WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan combined. Worldwide, death estimates range from 20 to 100 million, with nearly 600 million (of 1.8 billion total people) becoming sick. Vaccines were developed during the pandemic, but most only alleviated secondary complications and didn’t prevent the initial infection. To this day, the Spanish flu remains the deadliest influenza strain in recorded human history.