The Beat Generation included some of the most influential, controversial, and celebrated writers of the twentieth century. Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs were among many whose experimental writing inspired the 1950s and ’60s counterculture. In Whatcom County, literary history and local history converge on Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder’s time as North Cascades firewatchers.

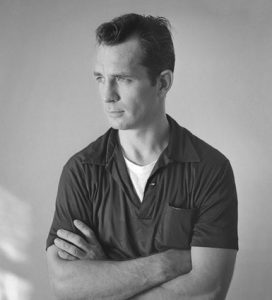

Born in 1922, Jack Kerouac most famously wrote On the Road , an autobiographical novel about his and Neal Cassady’s countrywide adventures. The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels recount Kerouac’s firewatcher job from summer 1956—just one year before On the Road’s publication. Kerouac passed away in 1969 due to alcoholism, but his influence lives on. Notably, he coined the term “Beat Generation” and wrote “spontaneous prose”—nonstop sentences that flow like breath, as in jazz and meditation.

Born in 1930, Gary Snyder won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1975 for Turtle Island. Snyder spent his early life mainly in King County and Oregon which, along with Zen Buddhism, inspired his poetry’s natural emphasis. “He was really the first sort of poet-environmentalist, with the exception of, say, John Muir or Thoreau,” says literary scholar and Western Washington University professor Christopher Wise.

Although brief, these writers’ North Cascades adventures have inspired similar excursions by many of their readers.

Snyder in Whatcom County

Gary Snyder was a firewatcher at Crater Mountain in 1952 and Sourdough Mountain in 1953. He convinced fellow poet Philip Whalen to become a firewatcher, and kept a journal published in Earth House Hold (1969).

Snyder first visited Bellingham while growing up in King County, and visited friends there during both firewatcher trips.

“There is this legend about Gary Snyder and Jack Kerouac coming into Bellingham” and visiting Cocoanut Grove, Wise says. A 1953 Earth House Hold passage says “Jack” showed Snyder the bar. However, the date does not match Kerouac’s trip and Conversations with Gary Snyder by David Stephen Calonne (2017) mentions one Jack Francis as a friend of Snyder’s in Bellingham.

Snyder made later Bellingham trips, including poetry readings at Village Books and North Cascades Institute in 2004. Having climbed mountains since 1945, Snyder knew the scenery well.

“When Kerouac was in Whatcom County, he had an encounter with a culture, with an experience of nature that he had never had before,” says Wise. “For Snyder, I think being here was more an extension of what he was already familiar with in Oregon.”

Kerouac and Snyder met in 1955, the year San Francisco’s Six Gallery reading featured Snyder’s “Berry Feast” and Ginsberg’s “Howl.” Snyder introduced Kerouac to Zen Buddhism and the firewatcher job while they lived at Snyder’s Mill Valley, California cabin—the experience behind Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums.

Kerouac and Desolation Angels

Jack Kerouac spent 63 days at Desolation Peak’s lookout station in the summer of 1956, resulting in Desolation Angels. He never spotted any fires, and had only brief radio contact with the U.S. Forest Service.

Desolation Angels (published in 1965) has three parts: “Desolation in Solitude” written in 1956, “Desolation in the World” written in 1956, and “Passing Through” written in 1961. The first, Kerouac’s firewatching journal, describes his struggle with boredom, isolation, and a self-confrontation “you don’t really see in his other narratives,” Wise says. The journal replaces Kerouac’s spontaneous prose with meditations on Hozomeen Mountain, comparing it to “the Void.”

“For people who really admire Kerouac, it can be a frustrating novel because of the rambling nature,” says Wise. “But I think it has a real heartfelt spirituality that still speaks to people today.”

From Marblemount and State Route 20, Kerouac hitchhiked to Seattle through Concrete, Sedro-Woolley, and Mount Vernon. “Desolation in the World” returns to spontaneous prose as Kerouac enjoys Seattle’s burlesque and reunites with friends in San Francisco. The Dharma Bums (1958) describes Desolation Peak in spontaneous prose, more optimistic in hindsight.

Desolation Peak may have been Kerouac’s last real adventure, as “Passing Through” recounts following trips more cynically. Visiting Tangier (a Beat cultural hub) in 1957, Kerouac felt “nausea concerning experience with the world at large” and lamented On the Road’s newfound fame. Big Sur (1962) is Kerouac’s only other novel set afterward, chronicling later health struggles.

To Kerouac, “Beat” meant “beaten down” but also “upbeat” and “beatific.” This sentiment resonates with his life story and with readers following the same road.

North Cascades Today

Hiking Desolation Peak takes a 10-mile overnight trip, Crater Mountain a 19-mile daytrip, and Sourdough Mountain a 10-mile daytrip. Lookout towers still stand at Desolation Peak and Sourdough Mountain.

Poets on the Peaks by John Suiter and a State Route 20 plaque near Desolation Peak commemorate the Beats’ mountain adventures. Still, Whatcom County feels the Beats’ influence in other ways.

“I see a lot in their writing that resonates with this particular county,” says Wise. “And some of their values, their ideals, their exuberance, the things that they loved, the experimental nature of their work…I think there’s an openness to that here.”

In the North Cascades, Whatcom County’s literature enthusiasts can hike further off the beaten path.

Featured photo by Christopher Wise