These days, George Miles’ memory is a little patchy. The 95-year-old Whatcom County resident has some trouble recalling the specifics of his past, but there is one memory he can’t forget: the morning he looked skyward and made eye contact with a Japanese pilot on December 7, 1941.

Miles is one of the estimated 300 remaining United States military survivors who bore witness to the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the primary event that led the U.S. to enter World War II. More than 2,400 Americans lost their lives that day. Miles, who grew up in Arkansas, was an 18-year-old radioman on the USS Antares, a cargo ship which spotted a Japanese submarine prior to the aerial attack.

“That morning, we were on deck, getting ready to enter the harbor,” he recalls. “We saw these planes coming in, and we thought they were ours.”

As history would prove, they were not.

The Day of December 7

During the early morning hours of December 7, the USS Antares steams towards Pearl Harbor after visiting the naval air station at Palmyra Island, a tiny atoll about 1,100 miles south of Oahu. In tow is a naval barge the ship will transfer to a tug boat before proceeding into the harbor.

By 6:20 a.m., the Antares is just outside the harbor entrance. As it prepares its barge for transfer, a suspicious object is spotted about 1,500 yards off its starboard quarter. It’s a Japanese midget submarine: a cigar-shaped, two-man submersible loaded with two torpedoes. Its mission is to follow the Antares, avoid the harbor’s anti-sub nets, gain entrance to Pearl Harbor and strike battleships.

The Antares alerts the USS Ward, a nearby destroyer patrolling the harbor entrance. Around 6:45 a.m., the Ward fires on the sub with 5-inch guns. The first shot misses, but the second strikes a direct hit on the submarine’s conning tower (its elevated compartment). The two men inside the sub become the first American-caused casualties of World War II. The Ward then drops four depth charges as a patrolling aircraft drops two more. The sub sinks. It won’t be recovered for 60 years.

Shortly before 8:00 a.m., the Antares is about to transfer its barge to the tug, the USS Keosanqua, when a large wave of planes is sighted. They’re far enough away that Miles and other soldiers think they’re American, as formations of fighters are common.

“They started peeling off one at a time,” Miles recalls of the planes. “They came up over the buildings (in the harbor), and up went the buildings.”

With a clear view, Miles and others on the forward deck of Antares see explosions from Ford Island and Battleship Row as the bombs drop. According to the original deck log of the Antares, at 8:00 a.m., a single Japanese plane flies over the Antares and opens fire on it and surrounding vessels. Although other planes may or may not have flown directly over the Antares, the pilot of this plane is likely the one Miles makes eye contact with.

At 8:05 a.m., the Keosanqua, still next to the Antares, is able to return fire on the plane. About a minute later, a 1,760-pound armor-piercing bomb strikes the battleship USS Arizona, detonating an ammunition magazine and triggering a massive explosion. Engulfed in an oil-fueled fire, the Arizona sinks within minutes, claiming the lives of 1,177 men and entombing many of them within the ship.

Miles leaves the deck of Antares, taking his battle station along with other sailors on-board. For Miles, that station is a small battalion locker, running emergency power for communications. While attending to his duties, he occasionally looks out at the continuing attack. Decades later, Miles says he wasn’t as surprised as you’d think, as everyone knew the Japanese military weren’t far from Oahu, and attack was always possible.

Around 8:35 a.m., Antares finally transfers its barge, and now has to move quickly as destroyers and other ships flee the harbor.

Miles recalls the harbormaster yelling for everyone to get out.

Around 8:45 a.m., the first wave of the attack ceases, providing only several minutes before the second wave begins. The Antares continues moving around outside of Pearl Harbor as the attack ends, and eventually is given permission to enter Honolulu Harbor and moor there.

Miles says men were then taken off the ship to form work parties, assessing damage to ships and beginning clean-up. The Antares remains there for a few days before venturing back into Pearl Harbor. By then, the U.S. is formally at war with Japan.

A Long and Lucky Life

After December 7, Miles continued his duties on the Antares, which was based out of Pearl Harbor for months following the attack. It was a quiet place the rest of the war, he says, except for nights when sailors went ashore for beers. Over the next couple years, Miles visited Samoa, Guam and numerous other islands. He still has visual memories of many tropical harbors, but can’t say for certain where they were.

“I was so young, and things were happening so fast, that a lot of it I don’t remember,” he says.

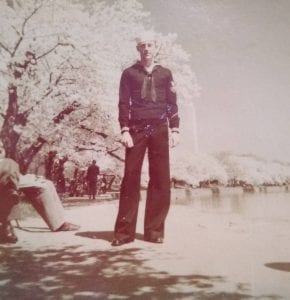

After the war, Miles briefly left the service to work his stepfather’s fishing boat in New Jersey. Upon re-entering the Navy, he was stationed on the USS Maury, a survey ship, and spent time in Greece and Gibraltar, a British colony at Spain’s southern tip.

In the early 1950s, while in the Boston area, George was set up on a blind date with Marie, a woman he had mutual friends with. The couple has now been married for over 60 years. Marie is 91. They have three children, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Miles and his family lived in the Philippines and several different American states before he retired from Navy service and settled here in 1961.

Eddree, their only daughter, was born in Hawaii in 1957. She recently moved onto the family’s apple tree-covered, 20-acre property to help her parents, who still live together in the modest home they bought just outside of Laurel.

“I’m very proud of my dad,” she says. “I’m very proud that he served his country.”

In Whatcom County, Miles worked on a commercial fishing vessel before finding working at the Intalco aluminum plant, which he retired from in the 1980s. At 95, he attributes his longevity to not smoking or drinking, always keeping busy, and walking a lot. The number of years, he says, doesn’t mean much to him.

“It’s just something you don’t even pay any attention to,” he says of his age. “It doesn’t bother me that I’m that old. I don’t feel too old.”

As to the significance of the attack he lived through, Miles says the lesson, 77 years later, is one of vigilance.

“It can happen again,” he says, of enemies striking the U.S. and changing the course of history.

With only single digit numbers of survivors from both the USS Arizona and USS Utah, and any military survivors being in at least their mid-90s, it’s possible we will lose the last living links to the Pearl Harbor attack within the next decade.

Jason Ockrassa, an interpretive ranger at the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument site in Hawaii, says a history professor once told him that we all die twice: once when we physically perish, and again, the last time our name is uttered. Remembering the attack, he says, isn’t just about the historical significance of the event; it’s also about keeping alive the names and stories of those who witnessed it.

“As historians, it’s our job to take these stories in,” he says. “We are the living ambassadors to these individuals.”

George Miles, decades removed from the day that could have ended his life, doesn’t dwell on his story much. He’s always preferred to look forward. And at age 95, he’s not about to stop.

“I was lucky,” he insists of surviving. “I was lucky in combat.”