Over the last 60 years, Tore Ofteness has worn a camera on the streets and into the skies, capturing the beauty and development of everyplace from Western Washington to Europe. His photos have proven important to both titans of industry and the local library system.

“I always kept a roll of film in my camera,” says Ofteness, 78. “Wherever I happened to be, I had my camera with me. I took photos of whatever I was experiencing, documenting it for no reason. I just felt compelled to do it.”

For the last decade, Ofteness has dealt with the ever-worsening effects of Parkinson’s disease. He no longer takes photos, but still works in the home office of his Silver Beach home as many days as he’s able, trying to finish a retrospective book of black and white Seattle images he captured in the 1960s.

“I just have days where nothing works,” Ofteness says of living with Parkinson’s. “It’s frustrating.”

The walls of his office testify to a lifetime dedicated to photography: plaques and ribbons from PAPA International — the Professional Aerial Photographers Association — and the Whatcom Art Guild, numerous books about photography, and many of his own framed images.

In 2018, PAPA International honored him with a lifetime achievement award.

Northern Exposures

Ofteness was born in Leknes, Norway — a village so small its entire population only owned two cars. One of them was a taxi, and the only roads to travel were a couple miles the Germans had built during World War II.

“If you went somewhere, you had to go by water,” he says. “It was an idyllic place to be a boy.”

In the spring of 1954, when Ofteness was 8 years old, his family moved to the United States. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean by ship, arriving in New York City as the largest family aboard. A press photographer took their portrait on the deck of the vessel; the image hangs in Ofteness’ office to this day.

The family’s move was sponsored by Ofteness’ aunt, and because she lived in Ballard — Seattle’s Norwegian stronghold — that’s where they wound up. Ofteness didn’t really like Seattle, so when he graduated from Ballard High School in 1963, he joined the Army.

After being stationed in Kansas for training, he was deployed—– not to Vietnam, but to Stuttgart, Germany — to work as an aircraft mechanic. The Army is where Ofteness first picked up photography, finding inspiration in the work of journalist Ewing Galloway, whose photography agency was once the largest in the U.S.

“We had a lot of dead time in the Army,” says Ofteness . “I wanted to fill my nights with something creative instead of just being drunk every night.”

Ofteness took his first-ever aerial photographs in the Army, foreshadowing his later career. Ofteness was discharged on his 21st birthday after three years of military service, and then spent a year exploring Europe, including a visit to Norway to see cousins.

Once back stateside, Ofteness volunteered at the City Collegian — Seattle Central Community College’s student newspaper — and gained his first real photography work. That led him to Western Washington University, where he became the first photo editor of Klipsun, the now long-running student magazine. Ofteness also did photo work for The Western Front, graduating from WWU in 1977 with a degree in European and African history.

Searching for post-grad work, he quickly found it from a series of local sources: Georgia-Pacific, Intalco, and his new alma-mater, WWU. The latter gig was his through a simple handshake and lasted until state budget issues in 1983.

That year was a particularly tough one for Ofteness. His first attempt at a downtown studio ended in a January flood of storm and sewer water, resulting in the loss of 15 years of photo negatives stored in file cabinets. Only work stored atop tables or shelves survived.

“My toilet became ‘Old Faithful,’” he recalls.

After that, his studio moved around over the years, and Ofteness’ career shifted mainly to aerial photos for construction companies and municipalities, the latter of which included the Port of Bellingham.

“It worked out pretty well,” he says. “Construction companies need monthly aerial photos for their big projects. It was a standard procedure for many, many years. Now it’s been taken over by drones.”

Looking Back

The aerial work also led to numerous photographs of Mount Baker.

Ofteness lost track of how many times he flew over the mountain with camera-in-hand. For 25 years, he worked to capture each year’s full moons rising over the volcano, and only missed a few of them.

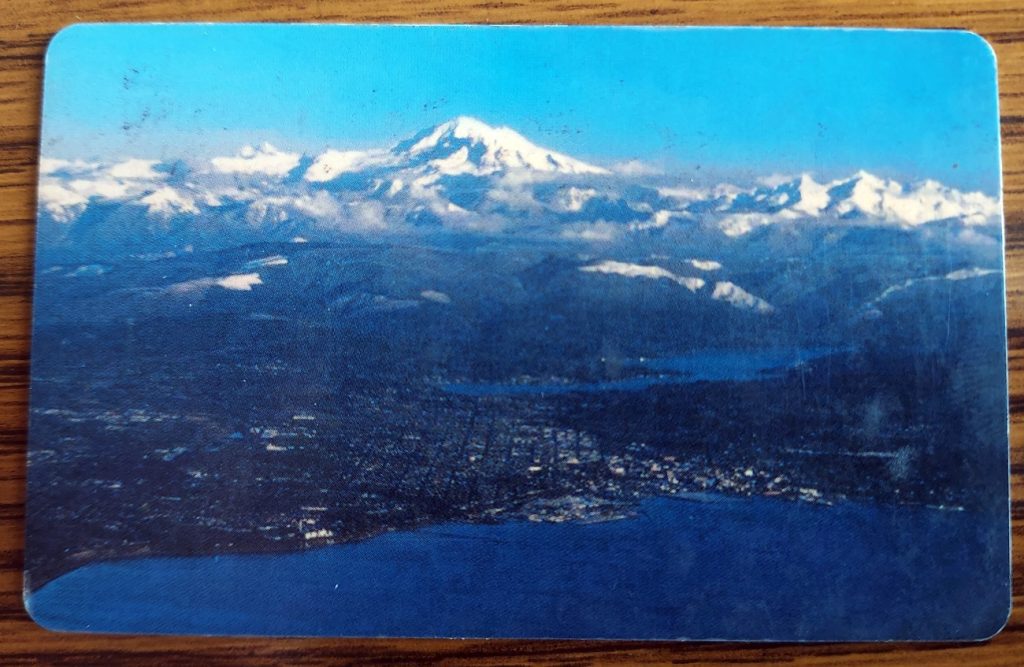

In the mid-1980s, Ofteness was asked to contribute an image to the county library system. Taken around 1985, the image of Bellingham, with Mount Baker behind it, was chosen as the image for Bellingham Public Library cards, and remains so to this day. Ofteness said he was somewhat surprised they picked his photo, but he still appreciates it.

Over the years, Ofteness advanced from film to digital, capturing everything from bridge building to demolitions. Although his photos can be found in many local spaces (including the men’s restroom of Boundary Bay Brewery), Ofteness said he never had a knack for selling non-corporate work.

“I’m not a very good salesman,” he says. “I’m pretty good at taking pictures, but selling them was a different story.”

A few years after his Parkinson’s diagnosis, Ofteness realized he no longer enjoyed aerial photography and retired. The best of his work is showcased in the 2017 book, A Higher Perspective.

Although he now lacks a darkroom for developing, Ofteness still sifts through his immense archive of negatives and digitized images. The Whatcom Museum already has many of his negatives and commercial work and will acquire the rest after his passing. Ofteness also posts images from his archive on social media.

“I like sharing,” he says. “What else do I do with them?”

Besides reviewing photos, Ofteness spends time with his wife of 37 years, Joan. Although he has no biological children, his stepdaughter took a photography-adjacent path: she teaches film studies and composition at the University of Illinois Chicago.

While he probably could have taken his talents anywhere, Tore Ofteness says he stayed in Bellingham because it’s simply such a nice place to live. When asked how he hopes to be remembered, he says it’s as someone who contributed to capturing the history of the city where he spent most of his life.

“I’ve always been interested in history and recording it,” says Ofteness. “It was just automatic, wherever I went.”