On a Monday afternoon in April 1895, 25 miners were hard at work inside the Blue Canyon Coal Mine on the southeast shores of Lake Whatcom. By the time their shifts were scheduled to end, only two of them would still be alive.

An explosion and gas leak that day took 23 lives, leaving widowed wives, fatherless children, and a shocked community. To this day, it ranks among the worst mining disasters in Washington State history and is the worst to ever occur in Whatcom County.

Blue Canyon Origins

Once coal starting being mined from the Bellingham Bay area in the mid-1850s, it quickly became — like logging —a key driver of Whatcom County’s early industrial development.

Coal was first officially noted in the Blue Canyon area in the mid-1880s, according to JoAnn Roe’s 1995 book “Ghost Camps & Boom Towns.” Commercial activity at Blue Canyon, however, didn’t take off until November 1890, when Fairhaven entrepreneur James Wardner began construction around an allegedly 13-foot-thick coal vein in a hillside above the lake.

To properly develop the site, Wardner needed additional funding. He found it with the “Montana Syndicate” — a group of wealthy businessmen that included Peter Larson and Julius Bloedel. Fairhaven’s J.J. Donovan also played a role, serving as the mine’s lead engineer.

By 1891, Wardner had sold his interest in the Blue Canyon Coal Mining Company to the Syndicate, and Bloedel purchased acreage for what would become the Blue Canyon town site. By March 1891, coal was officially being mined; by October, production was up to 50 tons a day.

As local historian George Mustoe told the Whatcom County Historical Society in November 2014, initial mining of the site was fraught with productivity issues. The coal seam was folded into the hill, causing miners to lose and then re-find the vein. This led to the construction of multiple entrances and shafts over time.

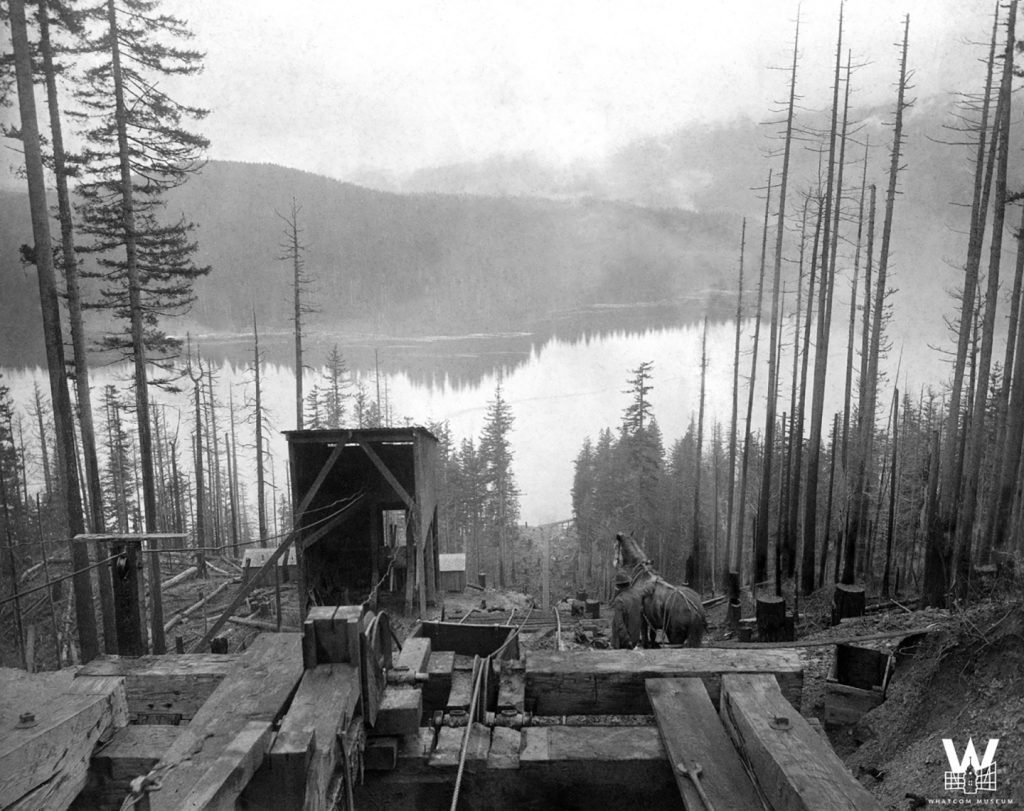

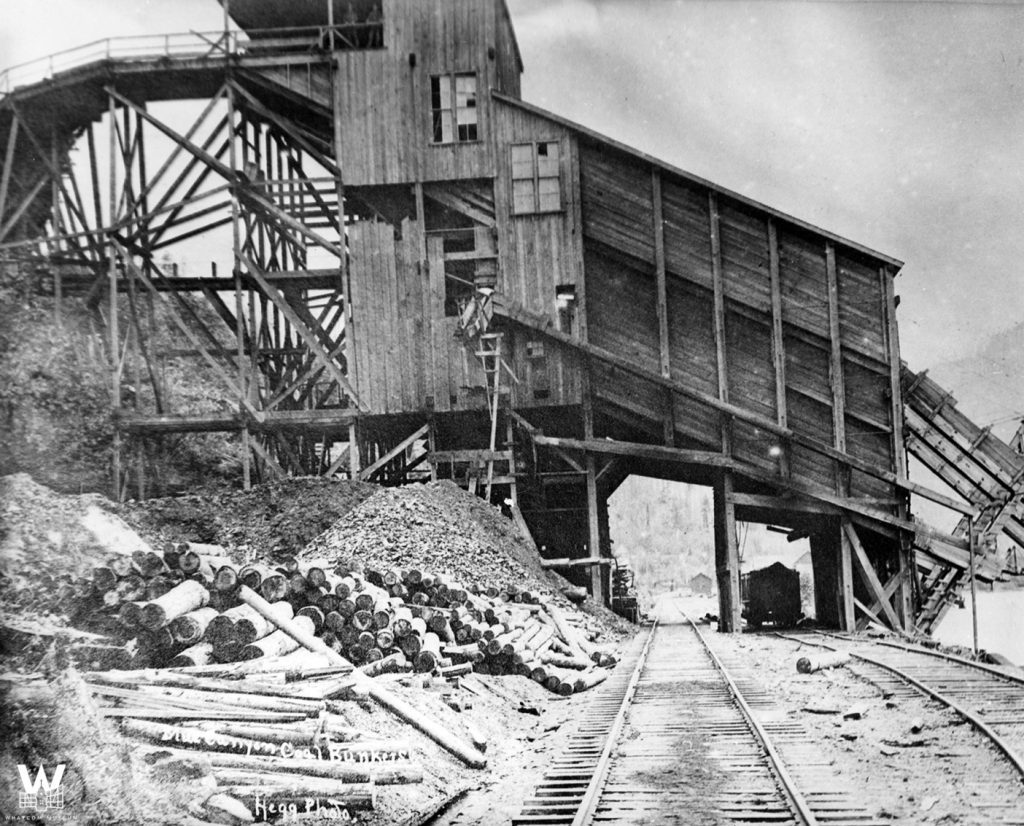

The process of getting coal out of the area was not easy: trams had to be built to send the coal down the hillside to bunkers beside the lake, where the coal was loaded onto rail cars that had been placed on barges. Those barges then crossed the lake to the nearest rail tracks at Silver Beach.

By April 1893, the mine was producing 200 tons of coal a day. It was also no stranger to accidents, as was the case for most coal mines of the era. In April, a gas explosion caused minor burns to one miner, and two months later a coal chute collapse killed another.

In 1894, the mine took on national significance when it landed a contract to power eight U.S. Navy warships that patrolled the Bering Sea. The townsite also grew alongside the mine, and by 1895 had 1,000 people and a three-story hotel.

The Accident

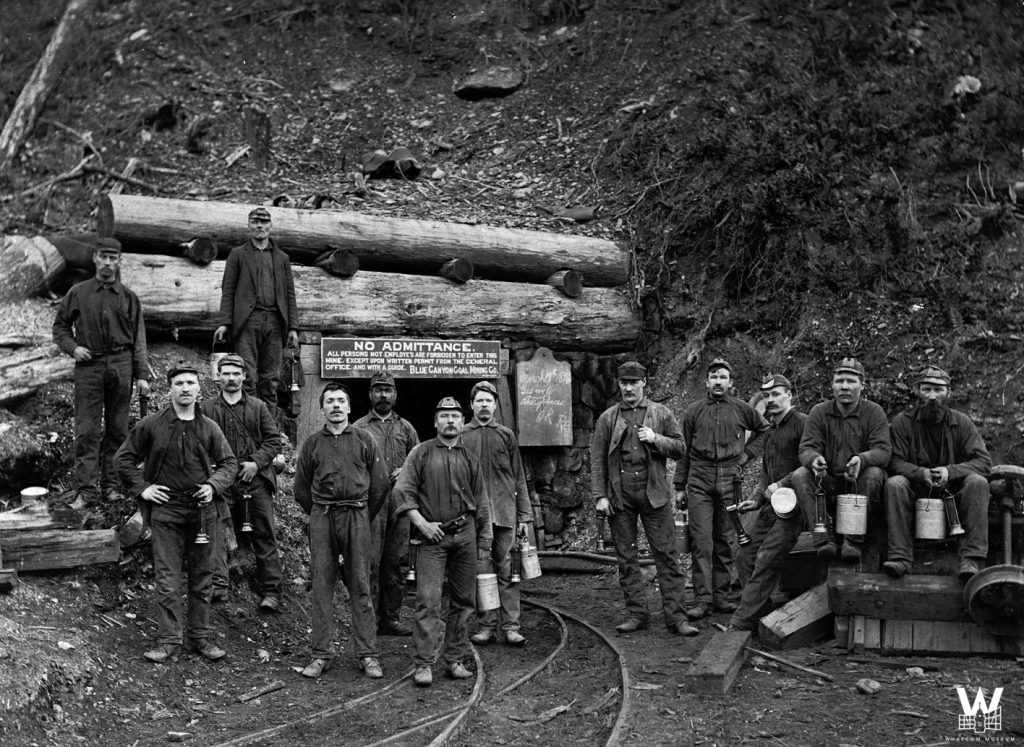

As a HistoryLink.org article describes, by 1895, mine access was an 800-foot-long tunnel leading to a 1,000-foot long gangway where mining carts were hauled by mules. Twenty-six rooms were cut at intervals into the coal bed, perpendicular to the gangway.

Around 2:45 p.m. on April 8, 1895, an explosion rocked an area of the gangway where the face of the coal seam was being worked.

Outside the mine there was little indication anything was wrong, until a mine employee working in a coal bunker heard a man, Tom Valentine, yelling from the mine entrance above him. Reaching the entryway, the man found Valentine with miner James Kerns, who was sitting dirty and exhausted.

Kerns had been working with partner Ben Morgan in one of the coal rooms when the explosion took place. Surviving the blast, the two went down a coal chute into the gangway, where their non-electric safety lamps met a lack of oxygen and went dark. Morgan reportedly fell and disappeared, but Kerns continued past bodies and coal piles to reach the main tunnel. An air shaft near the gangway and tunnel crossing supposedly provided him enough oxygen to remain conscious.

Mule driver Edward Gellon was behind a large support timber in the gangway when the blast occurred, having moved aside to allow mining carts to pass. The driver and mule directly next to him were killed, but Gellon was shielded from the blast and escaped.

As the two emerged from the mine, rescue work began. Although water-powered fans sent fresh water down airways to ensure safe entry, freshly-arrived miners found no one to rescue: bodies littered the mine. Those nearest to the explosion, a newspaper article claimed, were badly burned, while those furthest away bore no signs of violence.

Six of the miners had wives, and two had children.

The Aftermath

The 23 bodies were taken to the blacksmith shop near the tunnel entrance, then to another building to be washed. Among those doing the cleaning was New Whatcom Mayor Alfred L. Black.

Once placed into coffins, the remains were put onto a barge and sent to town. Two days later, the New Whatcom courthouse held a coroner’s inquest. Washington State Mine Inspector David Edmunds, who’d examined the mine just a month prior and found it safe, testified.

Edmunds placed no blame on the mine’s ownership and, in a later state report, wrote that an improperly drilled hole had been filled with dynamite and blasted, igniting a hidden pocket of methane gas that instantly killed seven miners. The remaining workers evacuated into the gangway and were killed by the carbon monoxide-rich air left by the explosion. Had they stayed where they were, it’s possible they would have survived, as the mine’s construction caused the gas to quickly dissipate.

The same day of the inquest, a period of public mourning commenced. Businesses and banks of New Whatcom and Fairhaven closed from noon to 3 p.m. for the miners’ funeral at Bayview Cemetery. There, 12 of the miners are buried together in section C; another seven are interred in section A. Four others, claimed by relatives, are buried elsewhere. The company paid for a black-marble monument with each of the miners’ names; it can be found to this day in section C of the cemetery.

The mine reopened a week later and set its single-day output record a month after the accident. But over time, Blue Canyon’s profitability and output diminished. The Navy converted its Bering Sea ships to oil, negating the need for Blue Canyon coal. It’s unknown if the two accident survivors resumed work in the mine.

In 1919, Blue Canyon closed for good. The following year, a spark from a passing locomotive caused a fire that burned the coal bunkers and other nearby structures. Logging exploits in the area took the place of mining, but over time, those too shifted elsewhere.

“A coal mine is labor-intensive and capital-intensive,” says Whatcom Museum archivist Jeff Jewell. “Blue Canyon, after the 1890s…it was too remote, and the market just wasn’t what it had been.”

An area near the mine site was once home to a rehabilitation facility, but it eventually closed. Today, the area where Blue Canyon coal mine existed is private property. The current landowners take trespassing seriously, Jewell says, and visiting is highly discouraged.

In the future, it’s possible the county could strike an agreement allowing public access through the area. But for now, public trail ends well short of connection with Blue Canyon Road, and the forested hillside where 23 men worked their last shifts.