For decades, an urban legend has persisted in Bellingham. Maybe you’ve heard of it: long ago, several Chinese miners were buried or drowned, accidentally or intentionally, in the old Sehome coal mine.

As a result, the miners’ spirits cursed Bellingham, leaving residents either unable to leave or destined to always return, no matter how they might try otherwise. It’s preposterous, of course. But where did this supposed “curse” originate? Did Chinese laborers really die in an old coal mine?

The answers — though hazy — are both intriguing and shameful.

Working the Black Seam

Coal mining was an important industry in Whatcom County’s early development.

The combustible black rock was first discovered in the mid-1850s at Bellingham Bay by Captain William Pattle, who was told of “black fire dirt” by local indigenous people. It wasn’t long before other claims were staked in what is now downtown Bellingham, and San Francisco investors helped organize the Bellingham Bay Coal Company. In particular, the Sehome Coal Mine eventually became very profitable for the company, to the tune of up to $300,000 a year (over $10 million today).

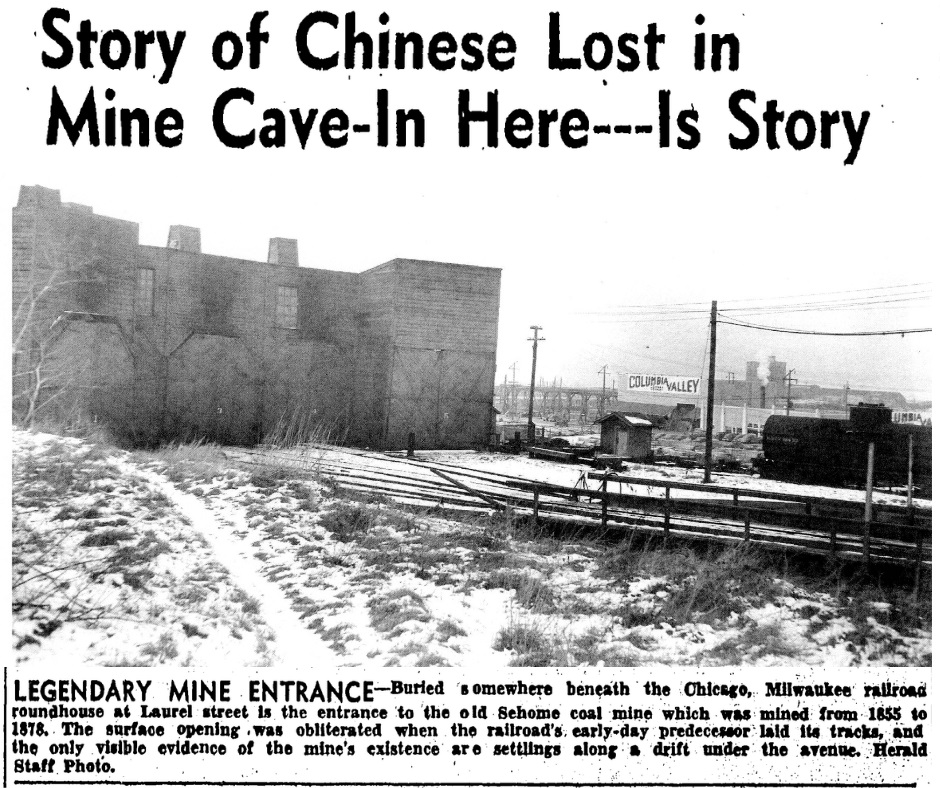

Like any coal mine of its era, though, it was dangerous. Accidents happened: in May 1863, several miners were hurt in a fire. In November 1866, saltwater was supposedly poured into the mine to put out another fire. In 1867, Dominick Padden — brother of Lake Padden’s namesake, Michael Padden — was killed in the mine. Sehome’s profit margin declined in ensuing years, and the mine was closed for good in 1878.

As time marched on, the expanding landscape of civilization filled in and paved over aging mine shafts and entrances to where laborers dug. In 1888, a Whatcom Reveille article noted a Mr. Hastings, who was employing a group of 20 men grading Holly Street to connect with 13th Street. Today, this connection point is near Champion Street, about four blocks from the coal mine location at Railroad Avenue.

“They are filling in the old cave hole,” the Reveille claimed, “where six Chinamen were buried in the coal mine a dozen years ago.”

Kolby LaBree, a Bellingham historian and proprietor of “the Good Time Girls” historical walking tours, has looked into this claim. In a 2020 blog post, LaBree says she couldn’t find any newspaper or journal entries from 1876 that support the disaster occurring. But the idea persisted through local media for decades, particularly when old mine shaft stories popped up.

A 1949 Bellingham Herald article’s beginning was particularly elaborate: “Do ancestral ghosts of dead Chinese haunt the sulphureous mine levels that underlie Bellingham? What secrets are contained in the rubble-filled passageways of the Sehome Coal mine, and what treasure? Seventy years have passed since the mine was abandoned, but the legend persists that it is a giant sarcophagus for unnumbered Chinese laborers, each with their life savings strapped to their skeletons.”

The article goes on to quote Morse Hardware owner Cecil Morse, who explains the second part of the story: the dead Chinese laborers were rumored to have gold in their money belts, and whoever dug deep enough might find their riches.

Jeff Jewell, Whatcom Museum archivist, says he thinks the treasure idea is at least partially why the story maintained staying power through the years.

“This is like the stories of when the Spanish explorers were here and, of course, left behind a chest of gold,” he says. “People really find lost treasure an appealing concept.”

Truth vs. Fiction

In addition to a shortage of historical evidence proving the disaster happened, both historians and old-timers have found the story devoid of validity.

Local author and historian Wes Gannaway points out that while Chinese laborers did work for the Sehome Mine (it was the only county mine that employed them), they did not work in the mine.

“Chinese (employees) worked at the loading dock, cleaning and sorting the coal,” Gannaway wrote in a 2007 Whatcom County Historical Society article. “This labor paid less than underground work, which Europeans took.”

Another version of the legend states that the mine flooded when workers “punched through the bottom” of the mine directly into Bellingham Bay. This is also untrue, as mine flooding to extinguish fires was done by diverting freshwater streams, Gannaway wrote.

Peter Denis, who was the last surviving Sehome miner when he was interviewed at age 89 in 1949, says he’d heard the Chinese mining story shift from nine workers buried in a mine cave-in at one location, to those same workers drowned in another location.

J.H. Pascoe, superintendent of the Bellingham Coal Mines on Birchwood Avenue, north of Squalicum Creek, said he was told by Henry Roeder that the story was made up.

Learning From the Past

A large part of the myth’s existence likely owes itself to something more shameful than tall tales: that of racism.

The 1949 Herald piece quotes an unnamed old-timer who said Chinese laborers were not very popular at the time the mine existed.

“No one liked the Chinese in those days because they worked for practically nothing and lived like misers,” the man said. “They were apart from the community and looked upon suspiciously. It was believed they had every penny of their savings buried under their floor or carried on their persons.”

And even if the story were true, it was followed by discriminatory laws that had a terrible impact on Chinese immigrants of the era.

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act banned Chinese immigration to the United States. This was followed by the regional Chinese expulsions of 1885 and ’86, where laborers were systematically driven from Seattle, Portland, and other towns — including those that would eventually become Bellingham.

As LaBree points out, the very paper that seems to have publically instigated the Chinese curse also blatantly promoted xenophobia: “For every Chinese employed,” the paper wrote, “an American home is destroyed.”

It even introduced a boycott of Chinese and their businesses, and residents who refused to sign had their names published in the paper to be shamed.

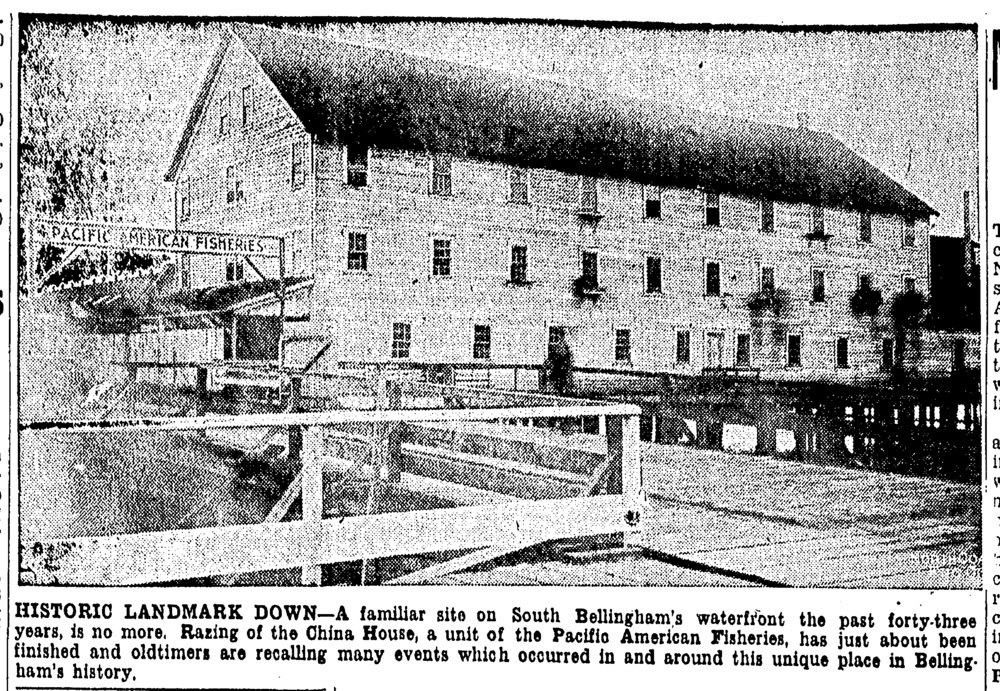

From 1898 to 1903, when Chinese laborers worked at the Pacific American Fisheries cannery in Fairhaven, they labored not far from the “Chinese Deadline” — a boundary rule to keep them from crossing Padden Creek and mingling with the rest of town. In 2011, Bellingham Mayor Dan Pike issued a formal apology for Chinese expulsion, and a new historical marker noting the deadline was placed where Padden Creek meets Harris Avenue.

While LaBree posits that Bellingham possibly deserved a curse for its treatment of Chinese people, she also sees the legend as a way of remembering and processing past treatment of local laborers.

Whether the “curse” has any sway on modern Bellingham, the mines from which it sprang still do. Jewell says maps of Bellingham Bay Coal Company mines were allegedly lost during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fires, leaving none to be consulted for modern construction concerns. As a result, test drillings must be done to see if part of, or how far, a mine is below a building site.

As someone who has long called the city home and understands the reasons for its growth, Jewell sees the idea of Bellingham being cursed as nonsense.

“I don’t see how always having to return to Bellingham is a curse,” he says. “If you could never return to Bellingham, that would be a curse. You could never go home again.”