Each spring, thousands of people descend upon the Skagit Valley’s large, brightly colored tulip fields to witness the vibrant blooming of spring in our corner of the world.

But a century ago, Whatcom County was actually the main draw for tulip-seekers. Beginning in 1920 and ending in 1929, Bellingham’s annual Tulip Festival celebrated the dawning of spring with parades, pageantry, and other festivities.

It was an event that drew people from well beyond the county’s borders and prospered greatly due to the confluence of several societal trends, including the growing normality of the affordable automobile and the economic prosperity of the “Roaring Twenties.”

Getting in Gear

Driving into Bellingham in 1920 wasn’t anything like it is today. Decades before Interstate 5 connected Western Washington from north to south, many people visited Bellingham via train or ferry.

That began to change in 1916 when Chuckanut Drive — a roughly 20-mile stretch of narrow dirt road clinging to the side of the Chuckanut Mountains and overlooking Samish and Bellingham Bays — opened to auto traffic as part of Pacific Highway 1.

Since the introduction of the Ford Model T in 1908, more and more Americans were finding themselves able to afford their first car. When a mix of city, state, and federal funds helped pave the northern-most portion of Chuckanut Drive in 1920, traffic to Bellingham picked up. By 1921, nearly the entire route was paved.

With individual travelers visiting Bellingham in their own vehicles, local businessmen like Henry Schupp — manager of the Leopold Hotel — encouraged the idea of tourism.

Jeff Jewell, Whatcom Museum archivist, says that while the area boasted a prodigious salmon cannery and lumber mills, those did little to differentiate Bellingham from other Puget Sound municipalities.

So Schupp and others hatched the idea to create a springtime draw to the city using the blossoming beauty of tulips. At the time, several tulip fields were located close to Bellingham, including at the present-day Smith Gardens area off Marine Drive and at a large government bulb farm site that’s now Bellis Fair Mall.

A commercial flower garden and bulb farm also existed off Northwest Avenue near the current Yeager’s Sporting Goods location; Tulip Road runs through the Columbia neighborhood where fields of flowers once grew.

Historically, Jewell says Bellingham area schools had previously held festivals in May, a time when sometimes mediocre early spring weather typically gives way to warm, sunny days.

So, in late April 1920, the city’s very first Tulip Festival commenced. For roughly two weeks, activities across the city celebrated the blossoming of spring, and local business owners — many of whom sponsored the festival — celebrated the increase in money being spent.

The Tulip Festival boasted a carnival — held on the current site of Bellingham High School — as well as the naming of a festival queen. Local businesses picked a series of adolescent girls as candidates, and whichever business sold the most Tulip Festival pins would have their girl declared the winner, Jewell says.

In 1925, Violet Sampley — daughter of City Attorney and Ku Klux Klan member Charles B. Sampley — received the honor of queen as the Rhododendron Club candidate.

Floating Away

The festival’s biggest event, however, was its parade.

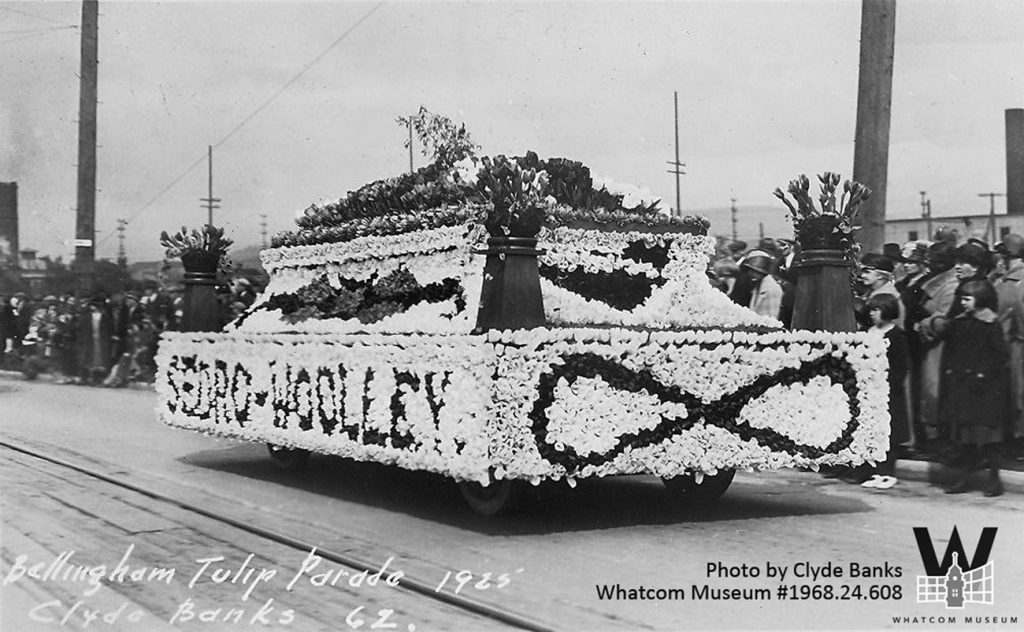

Every school, fraternal organization, and important community entity spent time and effort crafting their floats, many of which were set atop stripped-down automobile frames. Cities as far away as Vancouver, British Columbia, entered floats, too.

There were boats, dragons, and all manner of amusing entries; one year, a float from Lynden featured a very fake cow next to some very live chickens, which were encased in a makeshift chicken wire coup.

The well-spectated parade route, Jewell says, began along Holly Street around the area of Forest and Garden Streets, and proceeded down Holly for several blocks before turning onto Cornwall and several other streets. The first year, the parade actually went up Holly Street. Unsurprisingly, Jewell says this was never repeated.

The parade’s most controversial moment came in 1926, when the local Ku Klux Klan attempted to obtain a parade permit. Debate among parade committee members was fierce; at one meeting, several members threatened to resign over the matter. In the end, parade committee chairman J.J. Donovan denied the Klan a parade entry.

Through 1929, the late April-early May festival grew in popularity and stature, mirroring the 1920s building boom of downtown Bellingham. The Mount Baker Theatre appeared in 1927, and was joined two years later by the Bellingham Hotel — still the city’s tallest building. A massive addition to the Leopold Hotel was also completed that year.

With the Great Depression in full swing by the spring of 1930, the Tulip Festival was downsized to a children’s event — due to a decrease in both local business sponsorships and tourism. In the ensuing years, a springtime pageant for children would be held at Battersby Field, but it would bear little resemblance to the pomp and circumstance of the Tulip Festival.

A Lasting Legacy

In spirit, however, the Tulip Festival never really died.

After World War II, Bellingham revived its springtime celebration, sans tulips, with the “Blossom Time Festival.” Parades, carnivals, and festival queens graced Bellingham’s streets once more, and Blossom Time continued in name until the early 1980s.

In 1973, Blossom Time added a multi-sport relay race called “Ski to Sea,” which quickly became popular. About a decade later, the festival itself was renamed Ski to Sea, and it continues to this day each Memorial Day weekend. There is fun, there is excitement, and there is still a parade.

In looking back on the Tulip Festival’s decade of downtown prominence, Jewell views it as part of a ‘Golden Age’ in Bellingham’s downtown: when it was truly a community hub for the entire county, filled with local hotels, restaurants, and other businesses representing the growth and optimism of the era, and when the blooming of spring made just about anything seem possible.

“You can see how the trajectory of the Tulip Festival, which was just upwards, would have kept going,” Jewell says of its popularity. “Had the ’20s economy continued into the ’30s, we might still have a Tulip Festival.”