During the cultural upheaval of the 1960s, a vibrant countercultural scene bloomed in Fairhaven. This Bellingham community had lacked economic growth for decades, and many historic buildings had fallen into disrepair. The arrival of “longhairs” or “hippies”—proponents of alternative, lower-cost lifestyles—reinvented Fairhaven through lively hangouts, political action, and influential underground newspaper Northwest Passage.

“There was a lot of—six to eight thousand—new people that flooded into Fairhaven because the rents were so cheap,” says former Western Washington University political science professor and Northwest Passage contributor Bernard Weiner. “The demographic model changed drastically, from being a sleepy little college town to a kind of hip place where people wanted to live.”

In 1967, Western hosted national counterculture icons: Timothy Leary spoke there in January and Jefferson Airplane held a concert in Carver Gym in May. Ken Kesey’s “Band of Merry Pranksters,” including Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassady, attended the latter in the “Furthur” bus. However, Fairhaven’s counterculture scene lasted into the 1970s and only faded with modern development.

“When the military draft ended, the hippie era ended in a nanosecond,” says former Fairhaven promoter and Northwest Passage contributor John Servais. “Becoming sort of an alternative lifestyle place in the late sixties and early seventies, and then Ken Imus coming in, buying the buildings, that’s the big events in Fairhaven.”

Hubs (and Pubs) of Activity

Countercultural activity centered on Kulshan Tavern and neighboring Fairhaven Tavern, since 1968 and 1970, respectively. Servais notes that illicit activity was restricted to biker hangout Lockspot Tavern, later called Pluto’s, because of Fairhaven Tavern’s management.

Two mainstays of Fairhaven’s counterculture remain today: Tony’s Coffee and the Community Food Co-Op (now in downtown Bellingham). The Co-Op shared Morgan Block with Northwest Passage and Good Earth Pottery and used basement storage in Toad Hall, John Blethen’s pizzeria and coffeehouse.

“They made soups, daily bread, pizzas were really good, and it was a funky hangout,” Servais says of toad Hall. “Anyone could go there and start playing guitar or music in the corner.”

Kulshan Tavern and Toad Hall were among several establishments to disappear when developer Ken Imus bought their buildings. Imus was instrumental in developing Fairhaven’s Historic District but clashed with the counterculture, buying all but three buildings.

“What Ken really did for us was he saved those historic buildings,” says Servais. “Without Ken, they would have been knocked down, no question about it.”

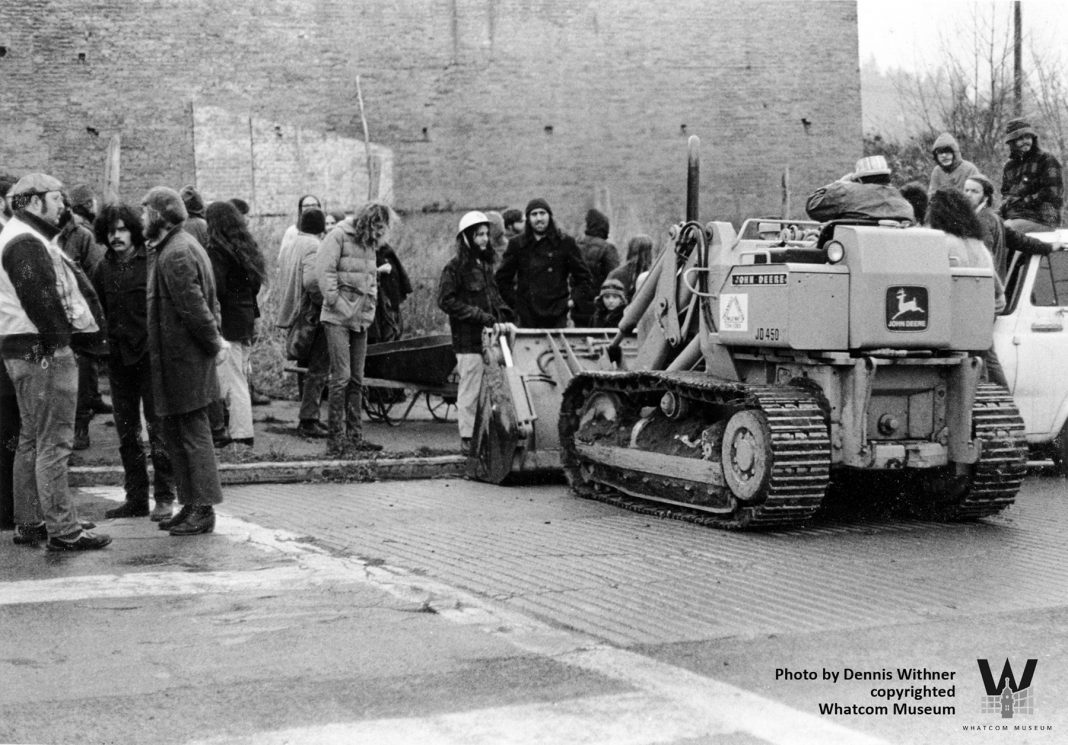

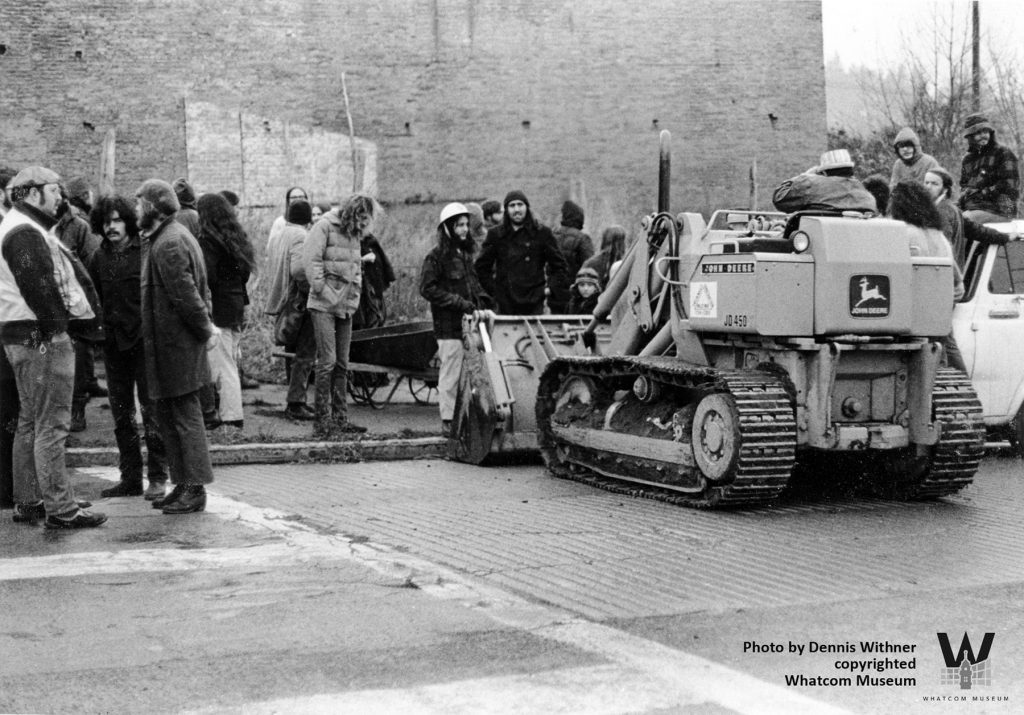

Many Fairhaven artisans moved on to La Conner, Servais says, transforming it into a modern tourist destination. Fairhaven’s counterculture receded as Imus continued development, a 1972 protest failed to prevent a community garden’s bulldozing, and national interest declined.

“It was like being present at the birth of a cultural change,” says Weiner.

Northwest Passage

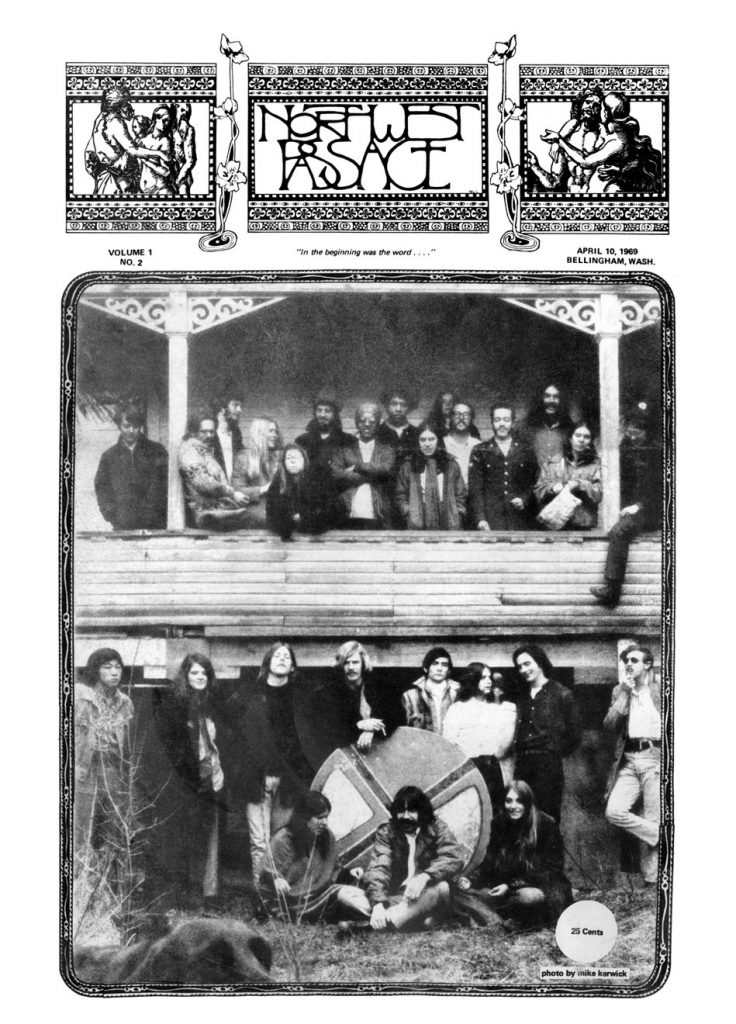

Frank Kathman, Laurence Kee, and Michael Harman launched the environmentally-focused Northwest Passage in 1969. It was an underground paper in the truest sense: authorities sought to shut it down. Printing operations moved from Bellingham to Lynden and finally Seattle.

“We would take the Northwest Passage paste-ups down to Seattle for printing and we’d bring back up a lot of food in bulk for the food co-op,” says Servais.

Northwest Passage’s investigative journalism exposed pollution at Georgia Pacific’s chlorine plant and Cherry Point Refinery, influencing cleanups and regulations that continue today.

“It was at that time one of the first papers—the first publications in the United States, we now realize—to have been writing some of the articles about the environment,” says Servais.

Northwest Passage secondarily featured anti-war and healthy living stories, and folded in in 1986.

“It was kind of a family after a while, we all knew each other well and worked well. Only a few of the editors had professional experience, but everybody was going to do reporting that needed to be done on pollution in Whatcom and Skagit,” says Weiner. “In the year 2000, I think, we had a reunion in Bellingham of the Passage and there must have been about 50, 60, 70 people.”

Where Are They Now?

Western Washington University’s MABEL (Multimedia Archives Based Electronic Library) is digitizing Northwest Passage. Many contributors have “become change agents in various institutions in the government in Whatcom County or state politics,” Weiner says. Bellingham and Fairhaven’s identities have remained a melting pot of contradictions since the sixties.

“We’re still in a transition from being a company town that worships big industry,” says Servais. “All these people like myself who’ve moved here, who’ve seen this as an environmental paradise with clean air, beautiful wildernesses, beautiful mountains, everything here that attracts us, we feel it should be more oriented towards that.”

However Bellingham’s identity may emerge in the future, the sixties revealed that cultural renewals burn brightest in retrospect.

“Everything that I’m talking about was happening sort of ad hoc at the time,” says Weiner. “We had no idea that anything significant was happening, we just were a part of it and a fun part of it—an important part.”