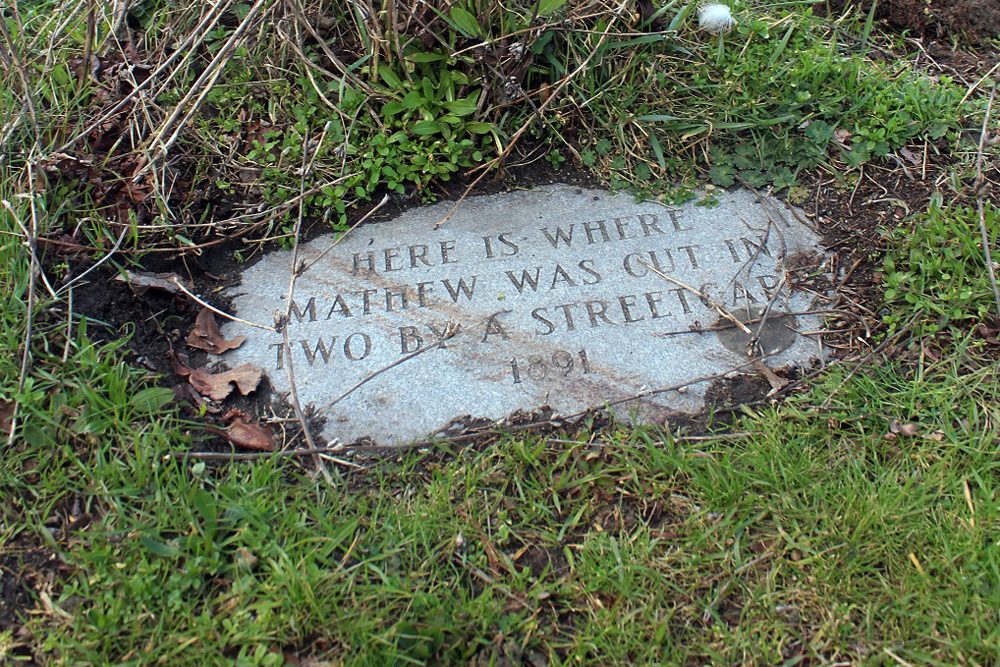

Along Fairhaven’s Harris Avenue, markers display years and brief descriptions of historic events that occurred where each one stands. These fixtures are as historic as the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century life they recall.

In 1988, Historic Fairhaven Association received a $5,000 community grant. Newspaper publisher and local historian Tyrone Tillson established the first 29 markers to communicate local history; a 1994 grant funded the next 21. Tillson recounted curious episodes in minimal detail, but those wanting to learn more may turn the stones and discover a fascinating town chronicle.

Before Fairhaven

Three markers on Lower Padden Creek and Larrabee Trail reference ages before the town of Fairhaven existed. The “Ancient Indian Campground” plaque alludes to state archaeologists’ 1973 discovery of firepits and artifacts dating back 2,800 years. These reportedly included spearheads, a labret worn on women’s lips, and remnants of a trail to the foothills. Artifacts apparently belonged to two groups, one Coast Salish and another from east of the Cascades.

Another marker mentions a “Spanish Massacre Legend” that, if true, would place Europeans’ regional arrival in the 1600s. The earliest recorded Spanish arrival was in 1791, when natives told them of a three-day battle between Spanish soldiers and multiple Puget Sound tribes on Padden Creek. The Spanish reputedly built a fort by Padden Lagoon and mistreated the natives, who ambushed and killed 400 of them. This story enraptured 1900s Fairhaven when newspapers reported an apparent fort mound containing a helmet, blunderbuss, copper plates, and skeletons. The “Picnic Beach” marker commemorates locals’ hunt for Spanish gold by the lagoon.

The trail’s “Spanish Chalice” marker references more possible evidence of the legend. Newspapers reported in 1908 that one Leigh L. Rose unearthed a chalice while gardening. He described elaborate figureheads on metal and alloy, the year 1630 inscribed underneath. However, no such artifact has resurfaced.

Frontier Fairhaven

Harris Avenue gets its name from “Dirty Dan” Harris, a Fairhaven founder notorious for his eccentric and crude behavior. He was a smuggler who arrived in 1853, building “Dirty Dan’s Cabin,” commemorated on the trail. “Dirty Dan Got Hitched Here” references Harris’ hotel—Fairhaven’s first, in 1883. It included an active bar but poor dining and housekeeping, which reportedly improved after Harris married Bertha Wasmer in 1885.

Many markers depict nineteenth-century Fairhaven as a “Wild West” frontier town with a seedy underbelly, particularly its saloon culture. Monogram Saloon was the site of a window-shattering 1892 gunpowder explosion; Butch’s Saloon and Capital Saloon the sites of shootouts. Junction Saloon became an outpost for town marshals to await railroad gang brawls, gathering men for the chain gang. Prisoners who refused were stockaded at the “Town Pillory.”

During the 1890s, Fairhaven’s red light district funded the police force. Its plaque marks brothels whose “madams” operated legally. Vigilante justice reigned until the “Town Marshall’s Office” opened in 1890. Its marshal, Winfield Scott Parker, reportedly fled to Buenos Aires with treasury money that he returned when the Pinkerton Detective Agency found him. The “Hotel de McGinty” marker commemorates a makeshift jail where vigilantes sent prisoners who could not pay court fees (per the “Courtroom” marker).

Fairhaven’s “Wild West” days continued into the twentieth century, declining toward Prohibition era. “Counterfeiter’s Hideout” references three machinists who faked payment for saloons, “Diamond Palace” a jewelry store owner shot for theft in Goldfield, Nevada.

Many plaques commemorate local tragedies, including a policeman shot 23 times throughout his career, one 11-year-old Mathew’s tragic death, and a “Drowning Pool” for unwanted dogs. “Unknown dead men displayed here in 1901” references the use of Morgan Block to identify transients and other victims of exposure and industrial accidents.

Industrial Development

Many markers describe Fairhaven’s turn-of-the-century developments such as “Fire Wagon and Hay Barns,” “Horse Stable and Carriage Shed,” and “City Garbage Dump.” The Interurban Trail bears a marker for “Fairhaven and Southern Railroad,” which hauled coal from Sedro in 1888 through 1898. This powered the “City’s Electrical Plant,” which turned off electricity every night at 10 p.m.

Markers also describe contemporary entertainment. “Cleopatra’s Barge” was a three-ring circus that paraded in 1891, attracting countywide crowds with performers and a menagerie that included lions, camels, and elephants. In town, people enjoyed performances such as knife-throwing at “Casino Theater” and films at “Apollo Theater.” “U.S. President Here” refers to William McKinley—a famous visitor to the Cascade Club at Mason Block (Sycamore Square) in 1901, as was Mark Twain in 1895.

Six markers allude to the history of Chinese and Japanese cannery workers at Pacific American Fisheries. Opened in 1899, this cannery employed thousands of migrant workers who occupied nearby bunkhouses.

The “Chinese Deadline” marker references discrimination barring Chinese people from 8th Street, updated in 2011 with a mayor’s apology. Today, the only trace of the cannery is the empress tree by the train station—a gift from Chinese labor contractor Goon Dip to company owner E.B. Deming in 1909.

Groups such as Good Time Girls offer guided tours through Fairhaven’s markers. It takes only a stroll down Harris to walk among the past.