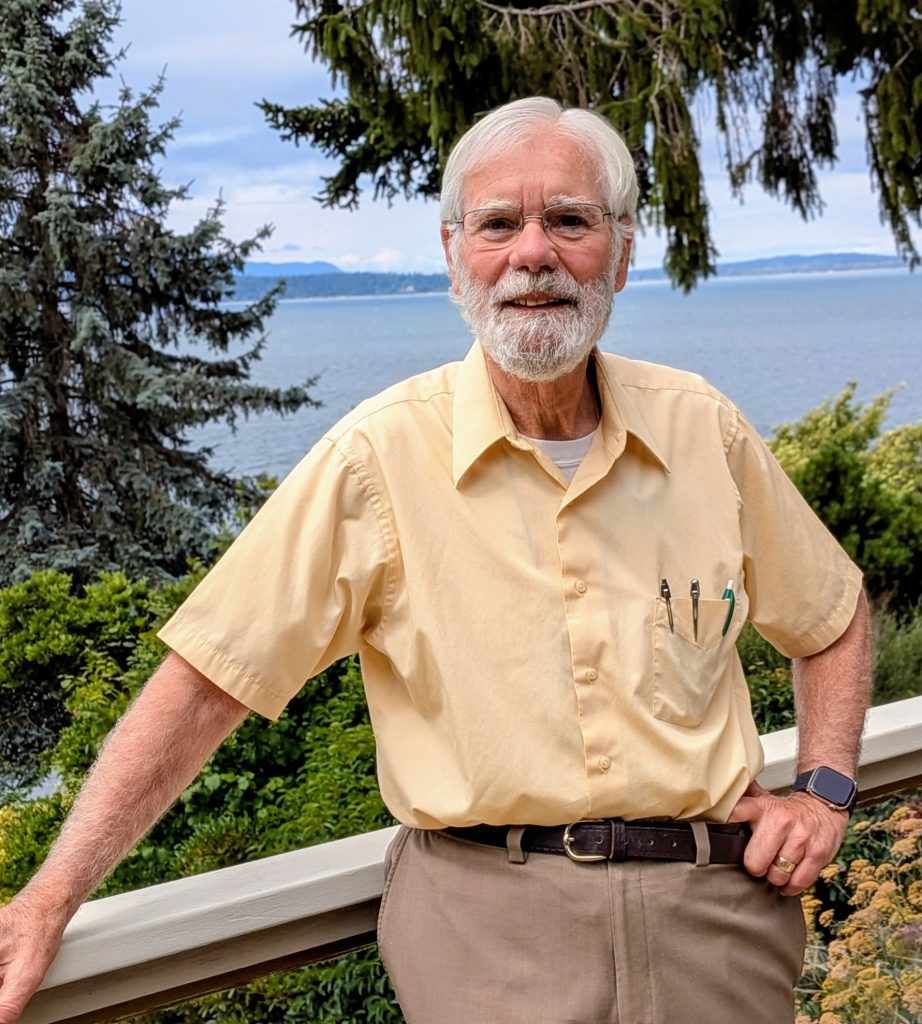

Ikh bin geboyrn gevorn Passaic, New Jersey. “I was born in Passaic, New Jersey.” Those were the first words Dr. Hank Levine learned in Yiddish in an in-person group way back in 1975. One can forgive him for not knowing much more until 2017 because his hectic career as a psychiatrist took precedence.

Now, semi-retired, the Bellingham doctor has not only returned to a pursuit of the language, but he also runs that very Yiddish conversation group called The Yiddisheh Ringele – The Yiddish Circle – meeting every other week online. People want to learn and practice Yiddish for a variety of reasons. A primary reason has always been that it was spoken in the home by parents and grandparents. Curious children were often eager to learn the secrets spoken in a different language.

Sixty-four-year-old Wendy Levin Westgate had been studying Yiddish for 15 years in Los Angeles when she moved to Bellingham in 2020. “I have a lot of ancestors for whom Yiddish was their first language,” she says. It followed that she would want to learn. In Los Angeles, she attended language classes with limited opportunities to practice conversation, so she was grateful to find the Ringele.

Generations later, as the parents and grandparents recede into memory, a new motivation among younger people has emerged with the revival of the Yiddish culture. Almost completely wiped out by the Holocaust, interest began to surge during another catastrophe, the COVID-19 epidemic. In a recent piece broadcast on NPR, Sarah Bunin Benor, director of the Jewish Language Project at Hebrew Union College, noted that there was a surge then, and, in the same NPR report, Duolingo indicated that 360,000 people worldwide are signed up on the site to learn Yiddish, half of them under 30 years old!

Origins of Yiddish

Yiddish and the culture itself derive from the amalgamation of the language, art, and music of different countries. Its history dates back about one thousand years. Jews had their own language and naturally began incorporating words from the languages of the countries in which they were living, predominantly France and Germany. German was the prevalent influence. The Crusades, having a huge political impact in Europe and the Middle East, drove Jews eastward toward Poland, Lithuania, and Russia. Soon, Slavic words entered the language.

While Hebrew and Yiddish do not sound alike, the Hebrew alphabet is the written form used by Yiddish speakers. Jews were always literate, given their devotion to studying Torah; hence, the Hebrew alphabet unified the Yiddish language across cultures.

Carrying On, Even Rediscovering, Heritage

Levine had had a desire to learn Yiddish for a long time. When he left his New Jersey home for college in Cleveland at 17, and eventually medical school, he took a Yiddish book with him, thinking he would have time to study. He did not; nor did he lose his connection to it. “I’m very oriented toward Judaism and history. They’re both very important to me. The sound of Yiddish sounded heimish to me.” Heimish is a fine Yiddish word that means from home and something familiar. “It was a sense of place for me,” he says.

Finally, 42 years after that first group he attended, Levine was settled in Bellingham and beginning to reduce the demands of his medical practice. In 2017, he had the time, so he joined the Ringele, then chaired by a woman who retired in 2024. Levine took on the Chair role.

How The Yiddisheh Ringele Works

Technology has been critical in the resurgence of studying Yiddish, with several online groups available, including YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Yiddish Book Center, and even Duolingo. You don’t need to join these groups to participate in the Ringele via Zoom twice a month for practice. People bring something to share, such as a story, a poem or song, something in the news, and the group talks about it in Yiddish and English. Many in the group do not know Hebrew. They use transliterations so everyone is on the same page.

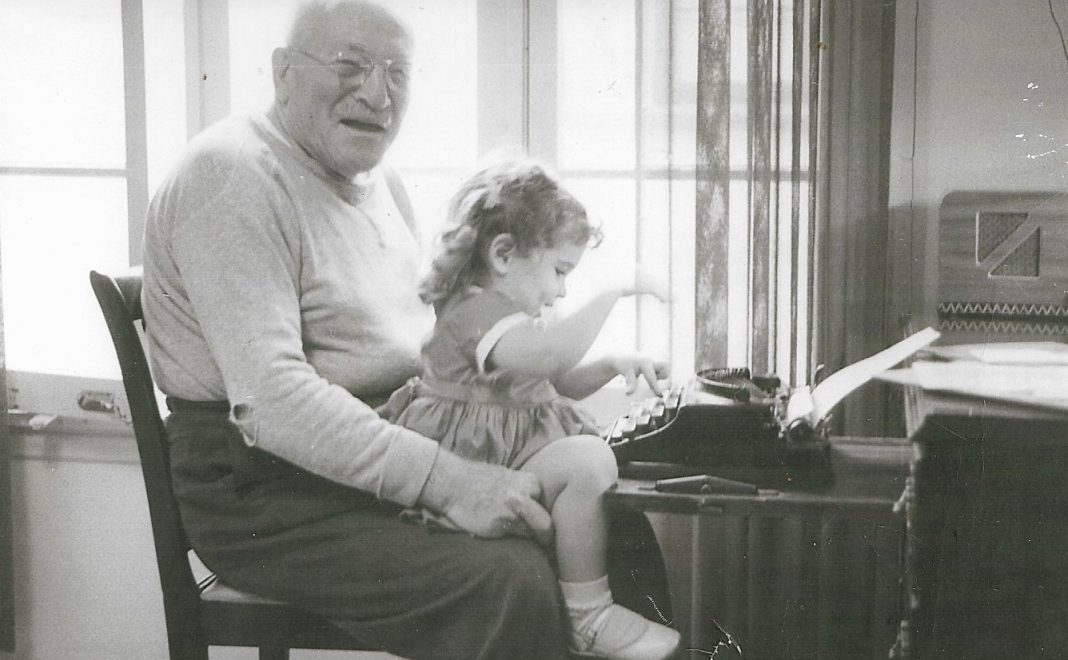

When it is Wendy Levin Westgate’s turn to share, she brings a selection of writings from her great-grandfather, written on a Yiddish typewriter. “I’m the family historian,” she says, “so I was thrilled when my mother gave me this parcel of pages between cardboard covers and tied together with string through perforated papers.” With the help of her Los Angeles teacher, Miri Koral, who happens to be a poet, Wendy discovered that it is a memoir of his journey from Russia/Poland to London to Chicago and was written in rhyme.

And then there is Maggie Weisberg. Maggie, at 101 years old, is a first-generation American, born in New York City. Her older brother’s first language was Yiddish. Her parents, her father from Lithuania and mother from Poland, who met in New York while taking English classes, spoke it at home, as did a grandmother who lived with the family. Maggie’s first language was English, “Partly,” she says, “because parents in that generation wanted their children to be American. Yiddish was looked down upon as the language of the diaspora. I didn’t like it. It was the language of old people and an old culture.” Maggie says she found the Ringele by accident when she met a man who came to The Willows Senior community, where she lives, for a Yiddish group meeting there. She was amazed that there was such a thing.

Now, Maggie says being part of the group has “connected me to my beginnings, to my family, in a very warm way.” She may bring her own writing to share or her son’s poetry. “Sometimes,” she says, “what we bring to share inspires lively discussion.” The involvement seems as essential as practicing the language.

Maggie’s son got her into computers many years ago, so she is quite comfortable with the present-day Zoom sessions. She adds, however, that “We sing happy birthday in Yiddish to participants and singing in unison doesn’t work so well on Zoom.”

The Ringele is an opportunity to share treasures, family histories, and cultural artifacts that need to be preserved. And it’s also a great way to be together. “We always start just by schmoozing and seeing how people are doing,” says Levine, “Ringele is an opportunity to chat and meet with friends.”

In other words, a place to feel heimish — at home.

For more information and to join the group, contact Dr. Hank Levine at hlevinemd@aol.com.