During the first half of the 20th century, Americans were fascinated by “human flies” who thrilled crowds by free-climbing tall buildings and doing acrobatic tricks. Three of these daredevils visited Bellingham during the 1930s. Their target was the same: the 15-story Bellingham Hotel at 119 North Commercial Street, known today as the Bellingham Towers.

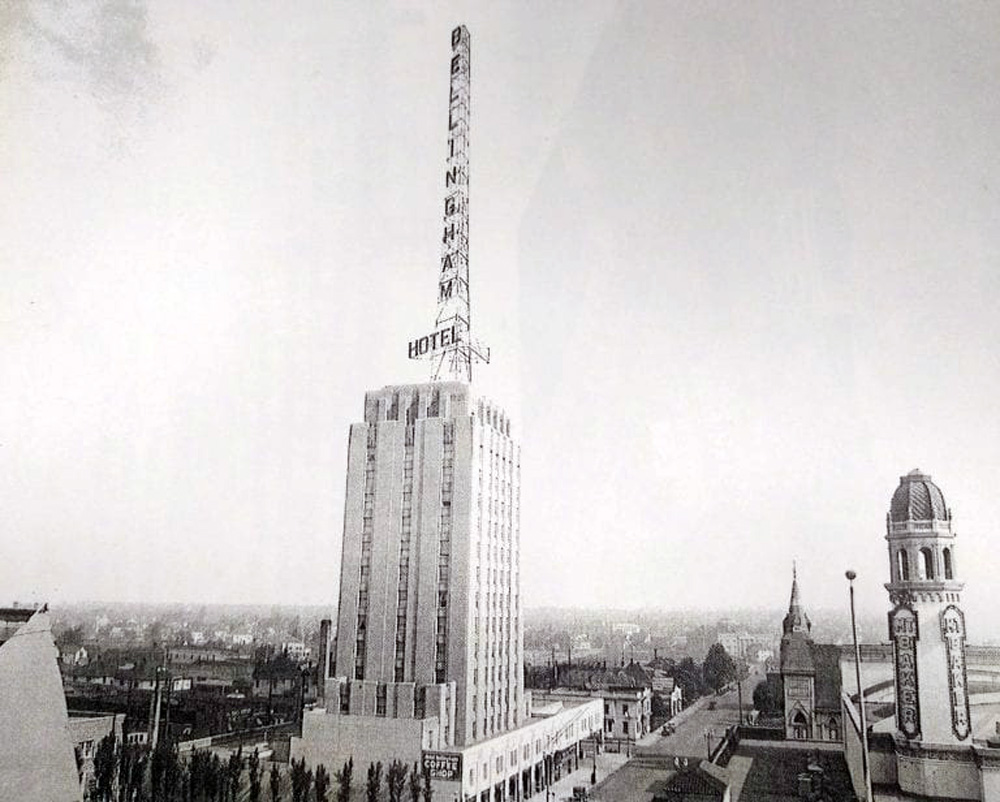

Built in 1929, the building was (and remains) Bellingham’s tallest. Sponsored by local investors as a “community hotel,” it was a symbol of civic pride. And atop the 157-foot building was a 162-foot-tall metal spire that spelled out the hotel’s name in seven-foot-high neon letters.

The hotel seemed a perfect challenge for people who made a living climbing the nation’s tallest buildings. Enter the “human fly.”

Henry Rolland, 1930

Henry Rolland was the first “human fly” to visit Bellingham. Born in Germany, the 38-year-old climbed many of North America’s tallest buildings of the era, such as the Chrysler Building in New York City. He even ascended Seattle’s Smith Tower in 1928.

Rolland climbed the Bellingham Hotel at 3:30 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. on August 30 and 31, a total of four times. At the top he was joined by his wife, Blannis, a former United Artist Studio stunt double, to perform balancing acts for the crowd. Many local students attended the evening shows. Newsreel men filmed his Sunday evening climb, which he performed blindfolded and under the glare of a spotlight.

Rolland took the time to talk to reporters after his climbs. While he had enjoyed the view from the top of the hotel’s electric sign, he told them, it had begun to sway in the wind as he did a headstand, making his perch “extremely precarious.” It was the tallest sign he had yet climbed.

The “human fly” also told reporters of his disgust for “cheaters” who used ropes for their climbs and for local “smart alecks” who wanted to join him on climbs but who overestimated their abilities. Rolland’s next stop was Vancouver, B.C.

Jerry Hudson, 1932

The second human fly to visit Bellingham was Jerry Hudson on August 10, 1932. Hailing from Montreal, he regularly performed across North America. Hudson was a veteran of the Royal Air Corps and an American Legion member.

Claiming to have climbed 7,000 buildings in his 18-year career, ranging from 5 to 65 stories, Hudson declared it took him only 10 minutes to ascend the front of the Bellingham Hotel, starting from the sidewalk. A large crowd gathered at 7 p.m. to watch him do a headstand on the edge of the roof. His quick ascension time —far shorter than later climbers — might indicate that he did not climb the spire atop. Luckily, his program did not need to be rescheduled because of rain.

Rolland Returns, 1935

Rolland made his spectacular Bellingham return when he climbed the Bellingham Hotel on the Commercial Street side on Friday, March 1, 1935. He scaled it twice, once at 2:30 p.m. and again at 7:30 p.m. Schoolchildren flocked to his evening climb.

The crowd, reporters for the Bellingham Herald gushed, “watched spellbound” as Rolland made it to the top “with the dexterity and sureness of the family cat climbing an apple tree in the backyard.” At the top, he was again joined by his wife Blannis. He gave her a piggy-back ride as he walked along the edge of the roof.

The spire, or top part of the hotel’s sign, was dismantled a little more than two weeks later, leaving only the word “hotel.” The manager cited economic reasons for the change.

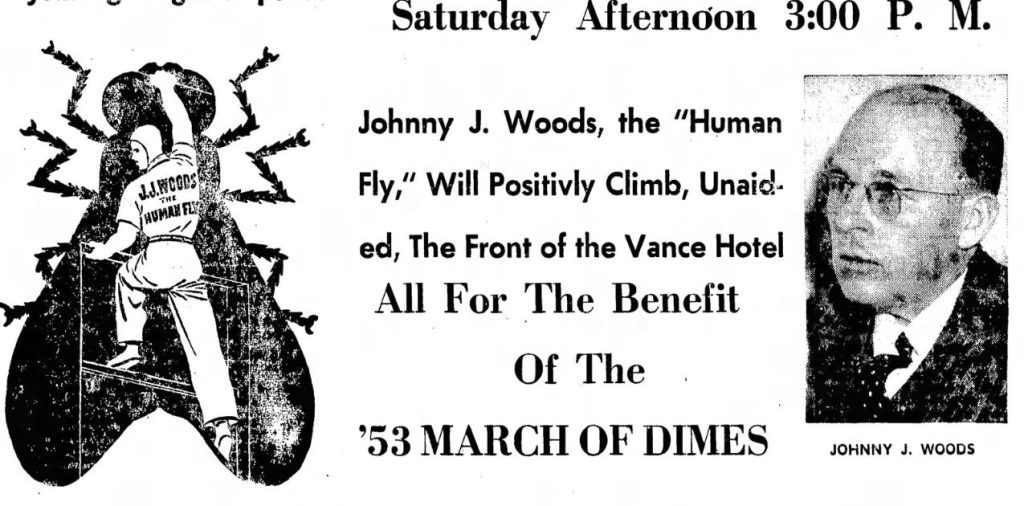

Johnny Woods, 1938

The final famous human fly to climb the Bellingham Hotel was 43-year-old Johnny Woods on February 17, 1938, at 3:30 p.m. Born in Atlanta and dismissed by his teachers as a clown, he began his climbing career early. He performed in Canada, the United States, and Mexico, ascending landmarks like Seattle’s Smith Tower and the Woolworth Building in New York City. He even doubled for Harold Lloyd in the 1923 film “Safety Last.”

With over 20 years of climbing experience behind him, Woods drew an audience upwards of 3,000 to watch him shimmy up the hotel in 33 minutes “without any more effort than it would take you to walk into the parlor and turn on the radio,” according to the Herald.

Slipping at the fourteenth story, he fell four feet before regaining his hold on a window ledge. Woods was lucky; Henry Rolland had fallen to his death during a trapeze act in Tennessee only the year before.

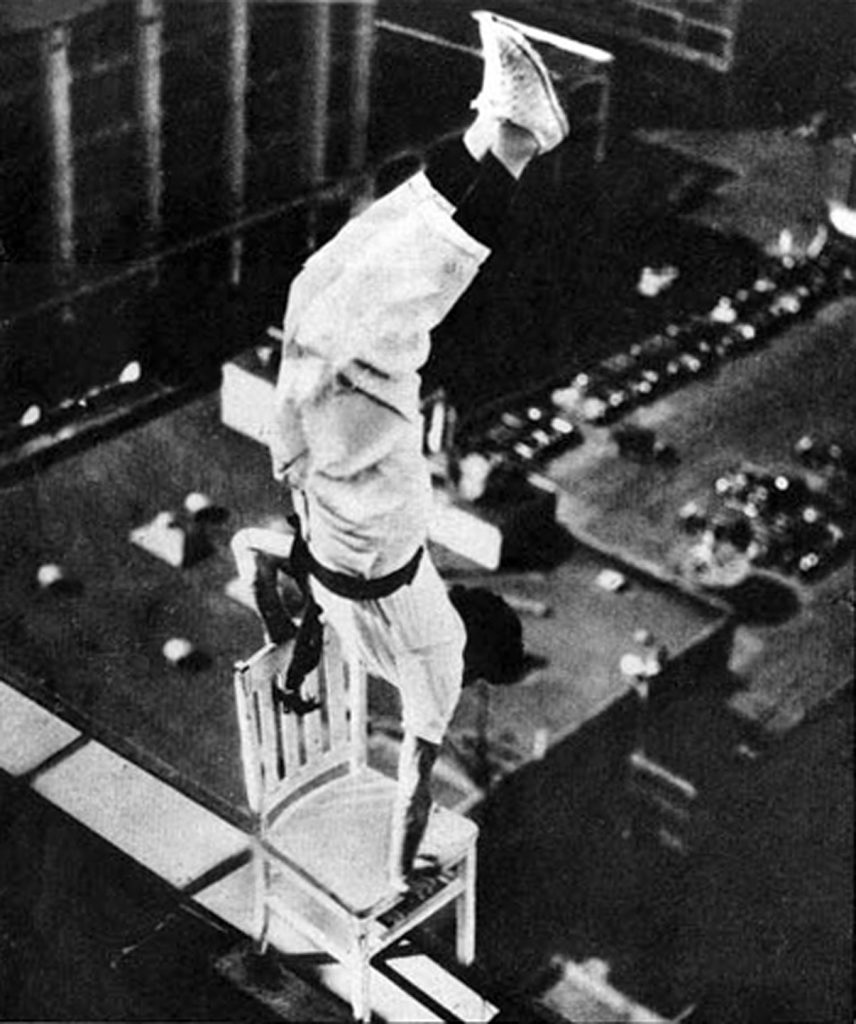

But Woods was undeterred. “It was easy,” he was quoted as saying afterwards. “I didn’t even get a sweat up.” Woods entertained the crowd by hanging by his toes from the top of the building, and then balancing himself on a chair on the cornice, one of his signature tricks.

He was joined on the roof by his wife, Evelyn. She sat on his shoulders reading a copy of the Bellingham Herald while he paced along the cornice, blindfolded.

Ever on the road, his next scheduled stop was the Georgian Hotel in Vancouver, B.C. Woods continued to perform into his 60s.

Much has changed in Bellingham since the “Human Flies” visited. The Bellingham Hotel long ago transformed into the Bellingham Towers. But during the dark days of the Great Depression, these daredevils thrilled audiences with their death-defying climbs. If they could do the impossible, what more could ordinary people do?