During the 19th century, the four separate towns of Bellingham, Whatcom, Sehome, and Fairhaven faced uncertain futures. Pioneer towns across the Puget Sound saw potential to become the region’s earliest metropolises. The four towns on Bellingham Bay shared ambitions that Tacoma and Seattle ultimately realized: hosting the terminus of a transcontinental railroad.

Whatcom first pursued the Northern Pacific Railway, which stretched from Lake Superior to Puget Sound and Portland, starting in 1864. Other cities in the running included Olympia, Anacortes, Seattle, and Tacoma, the last of which ultimately received it in 1873. New Whatcom later sought the Canadian Pacific Railway, stretching from Ontario, and Fairhaven the Great Northern Railway, stretching from Saint Paul, Minnesota—again to no avail.

Although the trains never came, the race for transcontinental railway access precipitated Bellingham’s development into a single city booming with industry.

Competition for the Northern Pacific

In 1869, Jay Cooke and Company inspected waterfront towns across the Sound competing for the Northern Pacific Railway terminus. Land speculation raged as Bellingham co-founder Edward Eldridge traveled with company agents by canoe. Although Whatcom promised a bay harbor and Sehome Coal Mine, the Secretary of the Interior concluded that a railroad would conflict with water transportation. Eldridge wrote circa 1890 that if the Northern Pacific had chosen Whatcom, “there would have been a city on Bellingham Bay of 100,000 inhabitants today.”

Northern Pacific Railway’s selection of Tacoma surprised land companies in Seattle, who expected the larger city to become the terminus. Seattle had offered $700,000 in money and land while Tacoma offered unsettled waterfront property. The railroad depot became New Tacoma, whose merger with the original town grew its population from roughly 1,000 to 36,000 between 1880 and 1890. Seattle would build its own railways to compete and expand over following decades.

Although the Northern Pacific bypassed Whatcom County, it ignited hopes for a railroad boom. Fairhaven pioneers J.J. Donovan and Nelson Bennett built the Cascade Tunnel across Stampede Pass, heralding Tacoma’s first vestibuled train in 1888. These entrepreneurs would set their sights on the Great Northern Railway, the next transcontinental line to buy local roads north of Seattle.

Bellingham’s Railroad Boom

Bellingham’s original towns grew as local roads emerged. 1883 saw the establishment of the Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railroad and Canfield Road, connections to continental Canadian Pacific Railway. New Whatcom’s June 22, 1891, celebration of the first Canadian Pacific train’s arrival notoriously started a “Great Water Fight.” Firetrucks that planned to create a water arch between Holly Street and Railroad Avenue instead sprayed each other, breaking train windows and drenching passengers. This incident and some youths’ trampling of the Canadian flag reportedly offended Canadian guests. Their terminal would not reach Bellingham Bay.

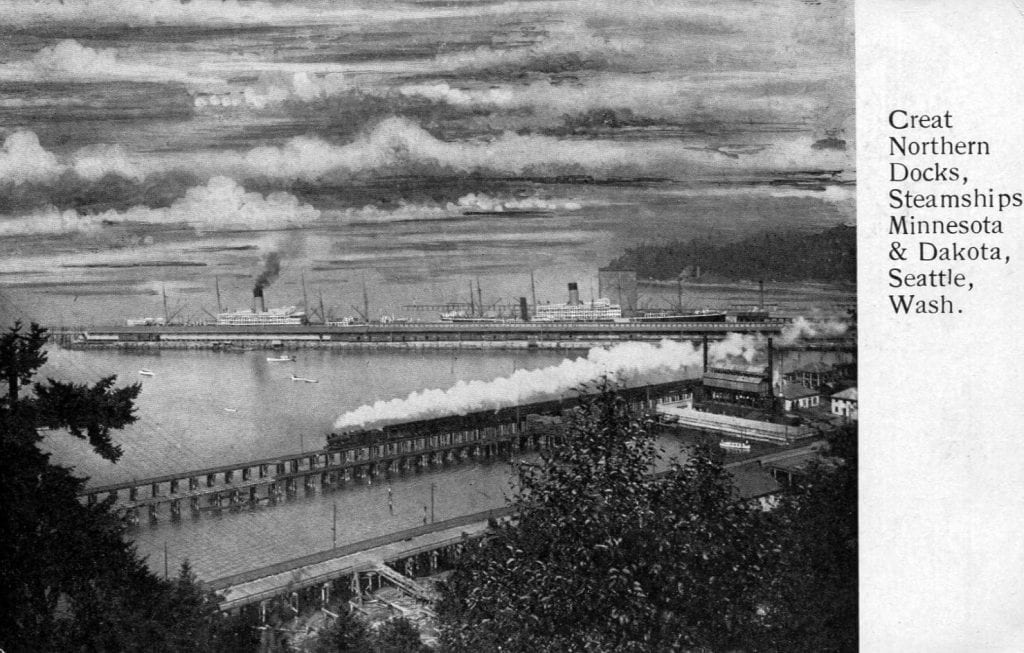

Starting 1898, J.J. Donovan oversaw construction of B.B. and B.C. extensions to Spokane, Glacier, and Lynden. In 1888, he joined Bennett, S.E. and C.X. Larrabee, E.L. Cowgill, and E.M. Wilson in establishing the Fairhaven and Southern Railway. Through the Fairhaven Land Company, they developed the area to entice the Great Northern Railway’s western terminus. The Great Northern soon bought Fairhaven and Southern and President James J. Hill reportedly said, “Here, Pacific Ocean steamships will meet their dock. Here, ships will meet rail. Here, you will have an Imperial City.”

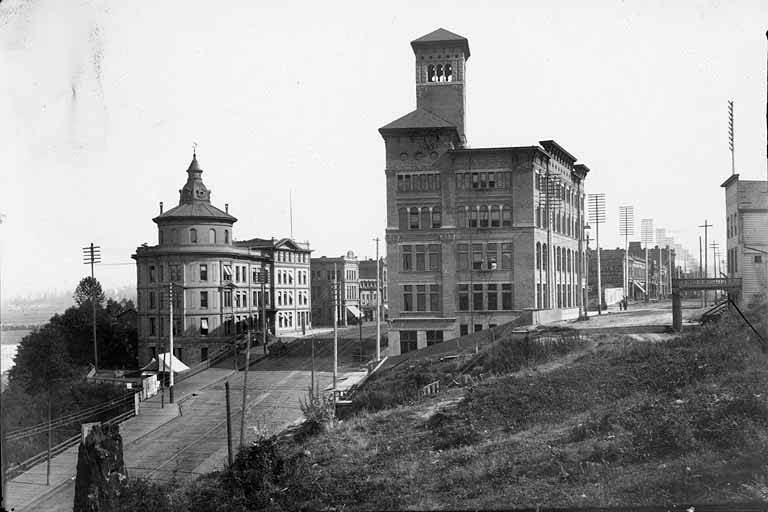

Fairhaven’s population boomed from 150 to 8,000 residents between 1889 and 1890. People arrived on steamships from Portland, San Francisco, and cities throughout the Sound to reap the benefits of Fairhaven’s growing industry. Hoping that Fairhaven would reach the grandeur of such cities, Bennett and Larrabee built the Fairhaven Hotel in 1890. This imperial structure, with 100 rooms, fashioned ornate classical architecture from red brick and Chuckanut sandstone. Businesses added “Imperial City” to their names, expecting Fairhaven to become a metropolis.

Hopes for an imperial Fairhaven faded when the Great Northern terminus went to Seattle in 1891, competing with the Northern Pacific Railway that bypassed Bellingham Bay once before. The panic of 1893 threw another wrench in the works: as banks failed and businesses shuttered, the boom had bust.

Chugging Along Into the Present

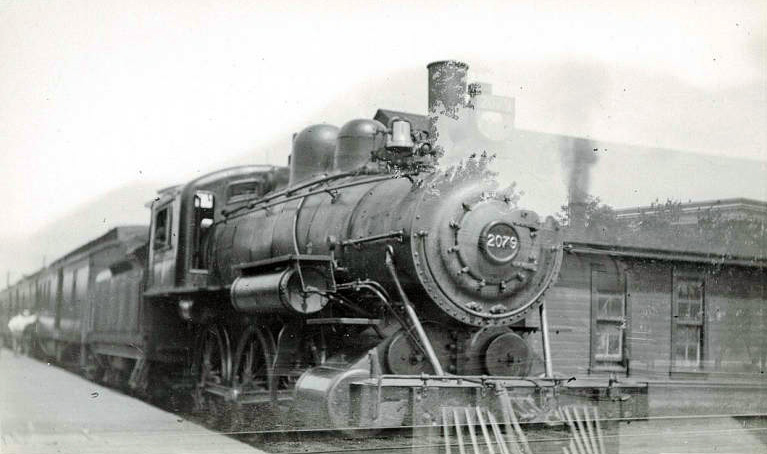

The 1903 consolidation of Bellingham into one city coincided with the national regulation of railroads as public utilities. The Milwaukee Road bought the B.B. and B.C. in 1912 and the Seattle and Montana Railroad Company bought the Fairhaven and Southern in 1898. The local roads kept Bellingham’s economic development steady long after the dream of transcontinental railways disappeared.

Some of Bellingham’s local rails still service modern companies, such as BNSF. Still others lie abandoned or have undergone rails-to-trails rehabilitation, as in the Railroad Trail, Interurban Trail, and Historic Fairhaven. Few historic buildings still attest to the influence of transcontinental railways—the Fairhaven Hotel burned in 1953 after Works Progress Administration renovations had stripped its ornamentation in 1928.

While the era of transcontinental railroads has long since departed, its influence on Bellingham’s development whistles on.