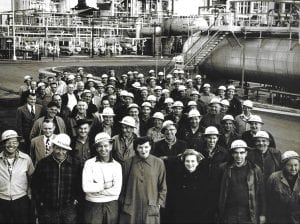

Sixty-six years ago, the Socony Oil Company closed its refinery in Olean, New York. But that wasn’t the end of the road for their many employees and their families. The company offered their workers a chance to travel across the country to Ferndale, Washington, where they would start new lives at the refinery being constructed there, now owned and operated by Phillips 66.

One hundred and thirty families took the company up on their offer and headed west. More than 2,600 miles later, they found themselves here in Whatcom County. Paul Madison made that journey as a child; his father was Bill Madison, a chemical engineer at the refinery. The whole Madison family packed up their lives in New York and came to Ferndale for a chance to start a new life in a new place.

“My father was working at the Socony plant in Olean, New York,” Madison reminisces. “They were closing that plant down and the company gave the people there the option to move out to Ferndale, Washington, of all places. They would also give you and your family a month’s lodging so you could have time to find a house and get squared away. At the time, that was kind of a far-reaching thing for a company to do.”

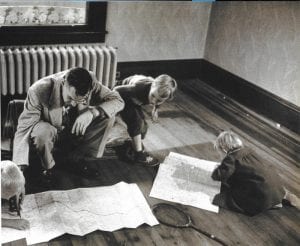

Madison was the oldest child, and describes the family’s journey that spanned the entire United States. “We basically just got in the car and Mom had all kinds of toys along the way. We spent a week traveling across the country. It was interesting because there was no interstate at the time; it was just two-way traffic. My sister was enthralled with drawbridges, and she counted them all the way out here.”

The voyage piqued the interest of LIFE Magazine, a major national publication at the time. “They chose us and one other family to document coming out here,” Madison says. “When we were packing to move, they were there and taking photos. They wanted tears from the kids, but my mom had been working like crazy so that wasn’t the case. When we got near Ferndale, they took more pictures of us. We got a lot of incredible pictures from that time.”

The family didn’t just get photographs from that trip: they found a home, too. “I’ve stayed here all my life,” says Madison. “So have pretty much all my sisters. We’re in Ferndale, Bellingham, Blaine. There’s about 20 miles that separate all of us. I went to Ferndale High School, and then Western. I was involved in the athletics department at Western for 50 years.”

Darby O’Neil’s family also came from Olean to build a home in Whatcom County. “My dad had been at Fort Lewis in Tacoma, so he knew what this area was like,” O’Neil says. His father knew that the refinery would support him, too; it had done so before. His father started working for the company in 1941, just before the war. “My dad got drafted for the war, and was out of work for three or four years. After, they hired him right back, and he retired from the refinery in 1976.”

Tim Springstead is another Olean transplant whose father had a long career with the refinery. Springstead is the son of Glenn Springstead, who worked at the refineries in both New York and Ferndale. Springstead’s father worked his way up from ash hauler to management.

“When the refinery moved to Washington, they wanted to take experienced workers like my dad and move them to 24 hour operations,” Springstead says. “My dad told them he had promised my mother he was going to work straight days or move back to New York.” The refinery obliged, and Springstead’s father moved from being a pipefitter to a supervisor, finally ending up in management.

“He was president of the union for years,” Springstead says. “In 1968, all the refineries had a nationwide strike. Out of that came the things you see today across the board: eight-hour work days, lunch and break rooms. Prior to that, you sat where you were working and ate your lunch. It was instrumental in starting OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Safety training and regulations came out of that strike. After working with the union, he became basically the head of the planning department, and he did that until he retired.”

Springstead remembers the refinery as a family-oriented place. “We could go out and see Dad, take tours. They built a refinery park out there. It was kind of bittersweet when I would go out there as an adult. It was like being with ghosts of all the adults I knew there. All the guys and their stories. That’s all they talked about; they lived for that refinery.”

Brandi Civico, the community relations coordinator at Phillips 66, says the feeling of family is important to the refinery community. “Family is a big deal,” she says. “Speaking personally, I’m fourth generation Whatcom County. I have deep roots here, and you can tell that the folks who moved out here have that same deep rooted connection. It’s still a small town, but it’s a big family.”

Sponsored